May 23, 2017; Reboot Illinois and Crain’s Chicago Business

With a new fiscal year just weeks away, the Illinois budget ticker has now passed 22 months without resolution. Over that period, as NPQ has frequently reported, the state’s universities and social service agencies have been particularly hard hit, as many state checks could not be written.

For those organizations lucky enough to be covered in special funding bills and court orders requiring state funding, the payment backlog is still many months long, forcing expensive cash-flow borrowing. Chicago Public Schools, the state’s largest school system, has remained open only by borrowing heavily to partly make up for these delayed state payments. Despite the pain, hopes for a compromise seem limited as politicians battle over governing philosophies.

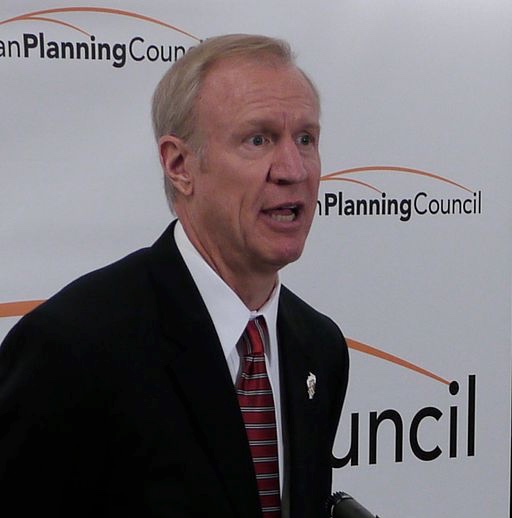

A small ray of hope shone through earlier this week when the Democratic-controlled Illinois State Senate passed a package of bills that included some of the government reform measures demanded by Republican Governor Bruce Rauner. It is an austere budget that reduces overall state spending by five percent and cuts a larger chunk out of state Medicaid contributions. Reboot Illinois quoted Democratic Senator Andy Menar describing this budget, revenue, and reform package.

We coupled this budget with a series of reforms that reflect our priorities, as well as those of the governor, including term limits on legislative leaders, school funding reform, pension reform, procurement reform and local government consolidation. Coupled with the reforms we’ve already passed this spring and ones will continue to look at, I think we are well on our way to sending to Gov. Rauner a plan that should meet all of his requirements to stop holding the state of Illinois hostage after two years.

Even this level of compromise seems insufficient. Republican leaders, who opposed the amount of taxation needed to fund a reduced level of state spending, immediately challenged the effort. Steven Yaffe, spokesman for the Illinois Republican Party, described the Senate’s actions as “another signal that all Democrats want is huge tax increases…Senate Democrats’ decision to ram through multiple tax hikes outside a comprehensive jobs and reform package confirms that the entire Democratic Party’s position is to raise taxes while protecting the status quo.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

There is no agreement in Illinois, as in many state capitals and in D.C., as to whether government’s problem is a revenue problem or an expense problem. Even when there is agreement on the specific woes that need to be solved, this divide makes solutions very difficult, if not impossible. No one argues that the base of Illinois’ public pension system needs to be strengthened, but two very different worldviews mean that defining the needed fix is not easy. Headlines often cited by fiscal conservatives spotlight a small number of retirees, usually school district superintendents and doctors teaching in the state’s medical schools, who receive six-figure pensions as examples of an overly rich pension system needing to be drastically cut. Led by Governor Rauner, Republicans have demanded “pension reform” and curtailing the rights of state employee unions as preconditions for an agreement.

A closer look at the reality of Illinois public employee pension systems tells quite a different story. According to a Better Government Society study published by Crain’s Chicago Business, for Illinois’s pensions programs “the median pension in 2017 for retired suburban and Downstate teachers stands at $52,016, the analysis shows, while the median for general state workers is $28,946. For university workers, the median pension stands at $26,101, while for non-public safety municipal workers outside of Chicago it is $9,064.” For the average state employee, a modest standard of living is the pot at the end of their pension rainbow. And, for most of these public employees, this is their only pension program; very few will also be receiving Social Security benefits.

Democratic leaders see the actual problem in Illinois’ pension programs as a funding problem, not one of benefits overreach—and the problem lies on the employer side of the equation. Every current and former public employee has contributed the required portion of their paychecks to their pension fund, month by month. It is their bosses who have not paid up. Required payments were “deferred” year upon year; now, the state now faces a shortfall of more than $100 billion. This decades-long pattern has meant that the costs of bringing these funds back into balance now eats up a major share of the state’s budget.

In fiscal 2016 alone, the state obligation…was $6.8 billion, an amount so large it consumed more than 26 percent of the day-to-day operations budget of Illinois government, according to Ralph Martire, executive director of the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability. But Martire said only $1.6 billion of that amount, less than 24 percent, was needed to cover the so-called normal cost of pensions, benefits actually earned by employees in 2016. The other $5.2 billion amounted to late payment charges. “The real problem is a debt-service problem and a tax-policy problem.”

For two years, the lack of political middle ground on this and other issues has prevented a state budget from being passed and may keep Illinois budget-less into year three. The release of President Trump’s proposed 2018 federal budget increases the potential for damage. If the budget that Democratic State Senators’ passed were agreed upon, Medicaid recipients in Illinois would start the new year with a program shrunk by $300 million in a state with no capacity to make up for the large reductions the president has proposed. Public schools and state colleges already strapped by inadequate state funding would be challenged to overcome the reductions in federal education funding Secretary DeVos has put forward.

With time running out, truth-tellers and advocates are needed in Springfield and Washington. The human cost of not fixing the real problems is too great.—Martin Levine