December 9, 2013; EurActiv

In Europe, despite reports about the “intensification of hate speech,” particularly against immigrants, Muslims, and Roma people, experts worry that the public is trivializing racism. The meaning of “trivialize” is to belittle, to make light of, to play down, to tone down. Is that happening in the U.S.?

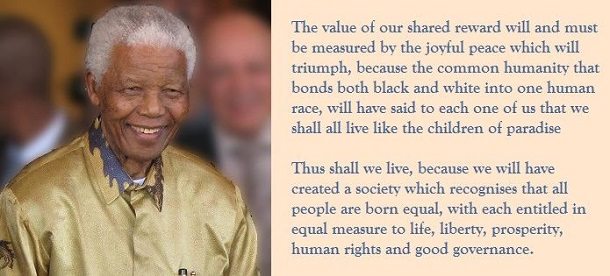

In the week in which the world is celebrating the life of Nelson Mandela, a man who confronted the most virulent, institutionalized racism of our time in the form of apartheid, it isn’t a bad time to ask whether we are as attuned to racism in our midst as we might be.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Certainly the Republican National Committee is a little off-key on the topic, given its congratulations of Rosa Parks for “her role in ending racism,” something that hasn’t quite occurred to date. It seems that the GOP’s effort to reach out to people of color needs a little conversation on the persistence of racism in our society. To be fair to the Republicans, Democrats, according to Washington Post columnist Ezra Klein, aren’t much more eager than Republicans to talk about race, because both parties like to hew (or pretend to hew) to the notion of “colorblind” policies, even if their results are racially skewed against the progress of people of color.

In the Harrisburg area of Pennsylvania, the Interdenominational Ministers Conference uses the term “quiet racism” to describe their members’ interactions with the area’s white population. Jamelle Bouie in the Daily Beast records a litany of examples of hard and soft racism—the police arresting three black students in Rochester while they were waiting for a school bus after a basketball game (the crime of “standing while black”), the arrest of two black dancers in Houston for escorting a 13-year-old girl (who happened to be their student) to an event, real estate agents’ continuing practices of discrimination against black renters and homebuyers, and the black arrest rate for possession of marijuana three times as high as the arrest rate for whites. But while not the racism of thugs, these are examples of racial bias in action.

More difficult to dig into and sort through are the examples of racial disparities that emerge from conditions that may not have much or any overt bias attached to them, or where the fact of bias is inconsequential to the emergence and persistence of racial inequities. A recent report from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation describes a large number of racial disparities in our society in health, income, wealth, employment, and education, making the point that closing those disparities would be a major societal boon in terms of GDP growth and other measures of economic progress. The combination of the racial biases outlined by Bouie and the racial disparities detailed in the Kellogg report add up to a picture of “the reality of modern racism,” which Mother Jones writer Kevin Drum describes as “not the bullwhips of 1850 or the fire hoses of a century later, but the constant, petty abuses, police stops, lousy schools, social wariness, and legal injustices that remain part of daily life for most African-Americans.”

As PennLive columnist John Micek observed this week, “Not talking about [racism] won’t make it go away. Pretending it’s not there doesn’t mean it’s not happening. This is a dialogue we need to have—no matter how uncomfortable it is.” But that also means talking about overt racism and the racism that occurs institutionally, societally despite the lack of obvious racial or ethnic animus. Until we begin to reach an ability to understand how ostensibly non-racial practices and policies can result is racially disparate outcomes and then take action to close those racial gaps, our society will be stuck on the issue of race and will revert to trivialization as a response.—Rick Cohen