April 25, 2017; Philanthropy Roundtable

“Some of our country’s most consequential giving was advanced by an all-star assortment of human train wrecks.” So begins this article in Philanthropy Magazine, published by the conservative Philanthropy Roundtable, which reintroduces us to some well-known donors with less-than-stellar character.

“The genius of our philanthropic tradition,” writes the author who goes under the pseudonym Grant Smith, “is that it takes people just as they are—kind impulses, selfish impulses, confusions and wishes and vanities of all sorts swirling together in the usual human jumble—and it helps us do wondrous things, despite our flaws.”

This opinion is not necessarily de rigueur, nor does NPQ share it—we believe to some extent that you are what you eat—but we thought there was some historic value in this romp through a garden of major donors we have (thankfully not) known. We have excerpted one profile here, but for the rest, you will have to go back to the original article.

“Smith” writes that John MacArthur became filthy rich in a cutthroat version of the insurance business.

A good fight was something MacArthur relished, and he waged spectacular legal battles with any competitor, authority, or tax collector who got in his way, often descending to nastiness and vulgarity.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

He was as unpleasant in his personal life. His reputation as a “bottom pincher” was a euphemism for what by many accounts was a long history of outright sexual harassment. He married his second wife, Catherine, by mail order in Mexico under bigamous circumstances.

He established the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation in 1970. Today, it is the nation’s twelfth-largest foundation by asset size. His motivations were not uplifting: he wanted to avoid an estate tax that would require selling Banker’s Life. He showed no interest in the foundation’s mission, declaring to his trustees that “I’m going to do what I do best. I’m going to make [money]. You guys will have to figure out after I’m dead what to do with it.” These instructions are frequently cited as an example of what philanthropists should not do if they want to protect their donor intent.

Fittingly, given its benefactor’s bellicose temperament, what happened after MacArthur died in 1978 was war. A struggle for control of the foundation board, and direction of its lucre, developed. Eventually, estranged son Rod MacArthur wrested the foundation away from conservative board members, turning it into a prominent funder of progressive causes.

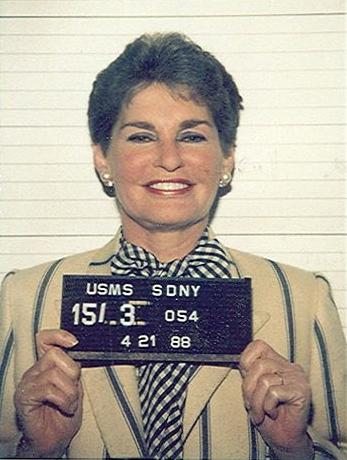

Also covered in this article about horrible people with loads of money and a philanthropic itch are Albert Barnes, Larry Hillblom (ugh), Henry Frick, Howard Hughes, Leona Helmsley, and Hetty Green.

We might argue that some of today’s donors certainly hold their own in terms of unsavoriness. One story we have been following suggests that a very large donor to a university is alleged, among other things, to have hired a hit man to take out his own son. We figure that may rate a mention from “Smith” one day when all is said and done.—Ruth McCambridge