Editor’s Note: As NPQ has covered, an entire industry of “economic development” engages in what is euphemistically called “business attraction and retention,” a practice of offering tax abatements and other tax breaks that reward corporations and cost state and local government between $45 billion and $90 billion a year. Corporate beneficiaries include Amazon, Walmart, and other large companies. Ultimately, the harm falls on state and local services, especially public schools, as economists such as Thomas Bartik have demonstrated. This article, which appeared earlier this month in an economic development newsletter, is a sign that at least some in this field, moved by our twin pandemics of COVID-19 and racism, are seeking to change their practices.

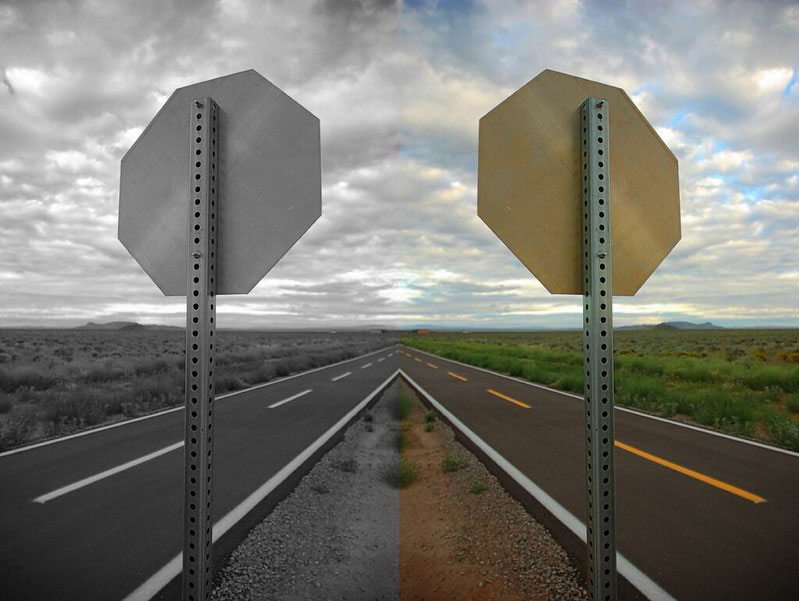

The post-COVID-19 economic recovery appears to be in full steam, but, as many observers have noted, it’s something of a K-shaped recovery. Instead of a rising tide lifting all boats, we’re instead seeing two competing trends at work. Some sectors and communities are booming. Meanwhile, there’s a long and growing list of those on the wrong-end of the K-shaped recovery: it includes microenterprises, Main Street businesses and downtown districts, tourism and hospitality, and [BIPOC]-owned businesses in general. Sadly, the challenges facing many of these folks are not driven by a K-shaped recovery. They were facing a K-shaped economy before COVID-19 hit.

Like many people, my hope is that we all strive to fix this mess. We build back better, as we’ve heard the politicians say. Building back better means many things—investing in infrastructure, building a stronger safety net, building more resilient communities, and so on. I believe that it also requires some new thinking from those of us working in the economic development profession. Our mission can no longer simply be about job creation. We need to embrace a broader mission of community building.

Many promising things are already underway. COVID-19 has triggered some excellent work on this front, so I’m feeling optimistic. Groups like the International Development Council and others are revising their programs and practices to embrace new approaches and ideas. Meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic spurred a host of innovations, especially in areas like small business finance, that are likely to inform current and future programs. And Washington is back in the game, making needed investments in critical federal programs.

Beyond improved and expanded programs, we may also need to rethink or update some of our fundamental ideas about what we do as economic developers.

Specifically, let’s think about the industry target for many economic development programs. For many of us, it is the traded sector company. Traded sector firms are those that sell outside of local market, and thus bring in new wealth resources. Along the way, they help to build a larger economic pie and create more prosperity.

This is a very good thing, and that’s why many if not most economic development programs focus on traded sectors. But, at the same time, that also means that the local sector—those firms that only do business in the local market—don’t get much attention.

COVID-19 showed that many of these Main Street firms operate with tight margins and are at high risk in the event of major shocks like a pandemic or economic downturn. But COVID-19 also showed that these firms matter in terms of economics, culture, and well-being. Local serving firms may not grow fast, but they are a strong and steady supplier of jobs. At the same time, they anchor our communities and create a distinctive sense of place. Who among us would prefer to go to McDonald’s or Applebee’s when we could hit a great local restaurant or watering hole? Finally, there is emerging evidence that vibrant Main Streets benefit our mental and physical health as well. In her new book, Main Street: How a City’s Heart Connects Us All, Mindy Thompson Fullilove shows how Main Street districts serve as community gathering spaces and how they actually enhance the health of local residents.

So, if these local anchors offer so much, why are we ignoring them? I’d argue that our economic development focus on traded sectors is one factor. I’d like to see us broaden this focus to support both traded sectors and what some researchers refer to as the “foundational economy.” The foundational economy is a concept that has emerged in European community development discussions. It refers to the parts of our economy that provide basic goods and services, such as food, housing, retail stores, doctors, dentists, car repairs, and so on. This mundane set of activities is obviously important in our daily lives, but it also has big economic impacts, as it accounts for as much as 40 percent of all employment. Using our current language, the foundational economy refers to those who are deemed “essential workers.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While these workers may be essential, they haven’t received much attention from those of us in the economic development profession. We have various small business and Main Street programs, but most traditional economic developers are focused on supporting traded sectors, technology firms, or the next sexy cluster.

From an economic development standpoint, the foundational economy matters in several ways. Most importantly, these jobs and industries are non-cyclical. Thus, they provide jobs in good times and bad. As we saw, even amid a raging pandemic, these jobs provide something of an economic buffer in times of economic crisis. Many foundational economy firms are locally owned, and thus provide many benefits associated with local ownership. Finally, the goods and services provided by foundational economy firms may exhibit unique local attributes, and thus contribute to creating distinctive and attractive places.

The role of the foundational economy is likely most important in helping to diversify the local economy, to stabilize economies in crisis, to provide local sources of employment, and to support local placemaking. These “services” are needed in every region.

A few European regions have embraced foundational economy strategies. Programs are now underway in Austria, Catalonia, and Scandinavia, among others. Wales has been an early adopter, and thus offers some guidance on what foundational economy strategies might look like. Beginning in 2019, Wales introduced a new set of foundational economy initiatives as part of a broader effort “to reverse the deterioration of employment conditions, reduce the leakage of money from communities and address the environmental cost of extended supply chains.” The project’s centerpiece was a Foundational Economy Challenge Fund designed to make small investments in pilot projects to test new approaches. The Fund supported dozens of ideas—like childcare collaboratives—using local microenterprises to deliver home care services and an online portal connecting renters to repair contractors. Another set of strategies focuses on the use of procurement to support local firms, somewhat akin to anchor institution programs here in the US.

This was a small grant program (around $6.5 million in total funds), and the pilots operated during the pandemic. So, we can’t expect big impacts yet. But the Welsh government has been pleased, and recently agreed to invest in an additional grant round with funds totaling approximately $4 million. In addition, discussions about a Foundational Economy 2.0 strategy are examining new ideas such as additional backing for firms in the social care sector and expanded support for food systems development. So, this is an experiment worth watching.

We may not have called it a foundational economy strategy, but much of our immediate economic response to COVID-19 certainly looks like one. We’ve made investments in restaurants, shuttered arts venues, ailing mom-and-pop businesses, you name it. And these investments are paying dividends—not only in preventing business closure and saving jobs, but also in maintaining community vibrancy and in ensuring that essential services, like childcare and transportation, are available even in a pandemic.

As we come out of the COVID-19 crisis, let’s not view those programs as one-off pandemic responses. Let’s make them part of our everyday toolkit in economic and community development.

This discussion of the foundational economy is not intended as an argument to neglect traded sectors or to no longer focus on industries that offer higher-paying jobs. However, I am arguing that we can walk and chew gum at the same time. We can support traded sectors and the foundational economy. By doing so, we not only help create new jobs. We also build better places that provide desirable goods and services and support better careers and lives for those working the foundational economy.

This article is reprinted by permission from volume 18, issue 1 of EntreWorks Insights.