August 4, 2019; Los Angeles Times

Much of the ongoing debate about healthcare policy focuses on those the current system leaves out—those unable to afford the high cost of care without public or private insurance. Less visible are those who have coverage and struggle to pay their growing share of doctor, hospital, and drug bills. As policymakers struggle to come up with solutions to the healthcare puzzle, the philanthropic sector has tried to fill a growing need.

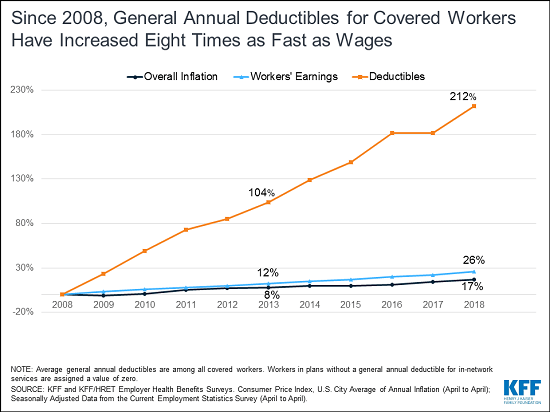

Most Americans are covered through employment-related health insurance. Policy arguments often start from the belief these programs work and don’t need fixing. But, as Bari Talente, executive vice president of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, says in a recent article by Noam Levey for the Los Angeles Times, “It’s not the uninsured who are the problem. It’s the underinsured.” For almost two decades, employers have struggled to cope with rising premiums as insurers reacted to soaring medical costs. Their response has been to increase the share of the annual cost of coverage passed back to their employees.

As wages have stagnated, the impact of paying their “share” has grown for middle-class workers, particularly those facing medical challenges. According to Kaiser Family Foundation’s Employer Health Benefits Survey: “Annual premiums for employer-sponsored family health coverage reached $19,616 this year, up five percent from last year, with workers on average paying $5,547 toward the cost of their coverage. The average deductible among covered workers in a plan with a general annual deductible is $1,573 for single coverage.”

When most Americans say they’d struggle to pay an unexpected bill of $400, these are daunting numbers.

The nonprofit organizations founded to support efforts to cure major diseases are being asked to help with the cost of care—often by people who have insurance but cannot pay their expected share.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Major patient support groups such as the American Cancer Society and the breast cancer organization Susan G. Komen report that most of the calls they receive seeking help come from people who have health coverage. FamilyWize, founded in 2005 to help uninsured Pennsylvanians get discounted drugs, calculates that at least three-quarters of the nearly 3 million people it serves nationwide are insured.

“More and more people who have insurance simply can no longer afford their medications,” said FamilyWize co-founder Dan Barnes.

Drug companies have, controversially, used their charitable foundations to help patients pay for pricy medication rather than directly reduce its cost. One in five prescriptions are estimated to be underwritten in this manner.

Industry support for these programs increased 14-fold between 1998 and 2014 and now tops $7 billion a year, a Treasury Department analysis found. Nine of the country’s 15 largest foundations, as measured by giving, are affiliated with drug makers, giving the companies large tax breaks while helping maintain high list prices. The largest—the AbbVie Patient Assistance Foundation—reported it gave more than $853 million in 2015, second only to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, according to data from the nonprofit Foundation Center.

These drug companies are helping individuals, but they are also helping themselves at the same time. Conditions that come with many of these efforts support their own high-priced products and ignore possible savings from lower-cost generics. Dr. Joseph Ross, a Yale internist, told the L.A. Times, “Companies look like they are doing the right thing to help patients, but in many ways, this is just a way to keep the gravy train running for drug companies.”

When established nonprofits and industry-related foundations cannot meet the need, individual grassroots fundraising efforts become a last-chance option. GoFundMe medical campaigns raise $650 million annually, and much of that goes to support families trying to meet uncovered health care expenses. Of course, this advantages those most able to mount a campaign, have large networks to call upon, and can navigate the crowdfunding labyrinth. According to Nora Kenworthy, a public health researcher at the University of Washington–Bothell, “These campaigns raise questions about who should be seen as most deserving, and they replace the notion of healthcare as a right with this hyper-individualized marketplace where people are forced to compete with one another to meet their basic needs.”

As we discuss how to improve our national strategy, we should not overvalue employer-sponsored insurance and assume it’s untouchable. Insurers and employers with bottom lines to satisfy will continue to see copays and deductibles as attractive solutions. Employees, often with little collective power to push back, will find themselves stuck needing help to pay the cost to remain covered.—Martin Levine