January 26, 2015; Devex

The news last year that Somaly Mam was starting a new charity dedicated to fighting human trafficking and sex slavery raises the question of how a damaged icon like Mam can rebuild her charitable brand.

Last year, Mam, leading the eponymous Somaly Mam Foundation, was exposed as having concocted part or all of her story of having been a sex slave in Cambodia and having pushed some beneficiaries of the foundation to lie about or embellish their own stories in order to get more donations for Mam’s charity. Although Mam fought against the charges, she eventually resigned from her own charity, which then lost funding support and closed down.

In January, Devex’s Lean Alfred Santos reported that Mam had created a new charity. The plans for the New Somaly Mam Fund were to have one office in Texas and another in Cambodia—the Texas office focused on fundraising, and the Cambodian office where recovery services would be provided on the ground to human trafficking victims.

Can Mam pull this off? The answer, most probably, is maybe, given the experience of other internationally known charities whose iconic namesakes have faced compelling charges that their stories were not quite true.

Remember Greg Mortenson? The author of Three Cups of Tea was slammed with charges that he fabricated big parts of his stories that led to his two best-selling books. Subsequently, he found himself in trouble with the attorney general of Montana for having used the charity, the Central Asia Institute, to promote his book and support his speaking tours as a means of self-enrichment. He was forced to pay a $1 million fine and was removed as executive director and voting board member of the Institute.

Donations to the Central Asia Institute plunged from $22 million in 2010 to $2.7 million in 2013, following the settlement agreement with the Montana AG. However, Mortenson stayed on as a paid staff member of the charity (at $169,000), stayed on the board (albeit without voting privileges), and the organization continued to promote his books without any agreement that it would benefit from the royalties. This month, the Central Asia Institute reported that 1,270 people who had stopped donating during the past two years returned to the fold and donations in 2015 were $100,000 greater than the $1.7 million the organization had received at this time in 2014.

From 2011 through late last year, Mortenson was excoriated for the stories in his book and his Central Asia Institute’s management and financial practices. He had his defenders, to be sure; some attacked author Jon Krakauer, whose report, “Three Cups of Deceit,” took Mortenson to task for his embellished stories of Afghanistan. A report on fundraising from the Central Asia Institute may be difficult to accept on face value. It might be accurate information that the organization’s management just happened to release (to the Associated Press) or it might be nonprofit fundraising bravado, meant to signal donors that the charity is back on the upswing—donors like giving to groups that are thriving, not sinking. Charity Watch’s Dan Borochoff is one charity watchdog that isn’t sold on Central Asia Institute, given Mortenson’s continuing role and other questions.

Almost two decades ago, multiple-time winner of the Tour de France Lance Armstrong created his eponymous foundation dedicated to cancer work. Two years ago, after aggressive denials of the charges and vicious attacks against his accusers, including former team members, Armstrong appeared on Oprah Winfrey’s show and admitted having cheated his way to the cycling titles through blood doping and other techniques. He left his foundation, which renamed itself the Livestrong Foundation after the rubber bracelets the foundation was known for distributing, and left the limelight—until recently, when he began participating in races again.

Despite its own fundraising bravado, Livestrong seems never to have recovered from its namesake’s troubles. Its 990s tell a story of plummeting income, increasing deficits, the reduced grantmaking:

|

Year |

Total Revenue |

Total Contributions |

Total Program Services |

Total Expenses |

Net Gain or Loss |

Fund Balance |

|

2013 |

$23,333,007 |

$14,648,378 |

$27,242,505 |

$31,355,029 |

($8,022,022) |

$99,715,485 |

|

2012 |

$38,077,668 |

$22,272,641 |

$31,932,539 |

$38,210,018 |

($132,350) |

$106,647,911 |

|

2011 |

$46,838,932 Sign up for our free newslettersSubscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox. By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners. |

$24,180,744 |

$25,606,149 |

$31,685,501 |

$15,153,431 |

$103,373,917 |

|

2010 |

$42,267,410 |

$28,879,762 |

$25,383,612 |

$31,553,407 |

$10,714,003 |

$90,605,561 |

|

2009 |

$41,770,001 |

$39,851,569 |

$24,056,363 |

$28,898,756 |

$12,871,245 |

$41,967,204 |

|

2008 |

$32,111,924 |

$30,506,682 |

$23,722,815 |

$27,638,323 |

$4,473,601 |

$27,037,477 |

Although Livestrong has had plummeting total contributions and, at least in the last two years, net operating losses, its robust fund balance and the income it has earned from a burgeoning stock market has kept it alive and financially stronger than many nonprofits, albeit with a reputational cost associated with Lance Armstrong’s untruthful statements about his use of performance-enhancing techniques to win his Tour de France races. While it has survived with a strong fund balance, able to maintain a highly paid staff, the foundation’s ability to raise money from private sources has dropped from almost $40 million in 2009 to $14.6 million in 2013.

Armstrong is no longer associated with the foundation, but he is acknowledged on its website as its founder. However, his bio, which notes that he is a cancer survivor and a philanthropist, doesn’t mention his now-forfeit Tour de France titles. Unlike Mam and, presumably, Mortenson, Armstrong had personal wealth estimated at $125 million when he left the foundation and still harbors a faint hope of returning to the foundation that asked him to leave the organization.

“I spent a long time trying to build up an organization to help a lot of people,” Armstrong told the BBC. “And I can’t lie: It hurts that that has been put away, or almost forgotten, and almost, in some parts of the world, discounted as if it was a sham or PR. It wasn’t. That was very real. It meant a lot to me. And the deepest cut was Livestrong saying, ‘you need to step away.’”

It may still happen. Last year, the Livestrong executive director suggested he would be open to Armstrong’s return to the organization, and Armstrong himself hinted that he might form a new cancer charity if he weren’t allowed to come back to the charity he founded.

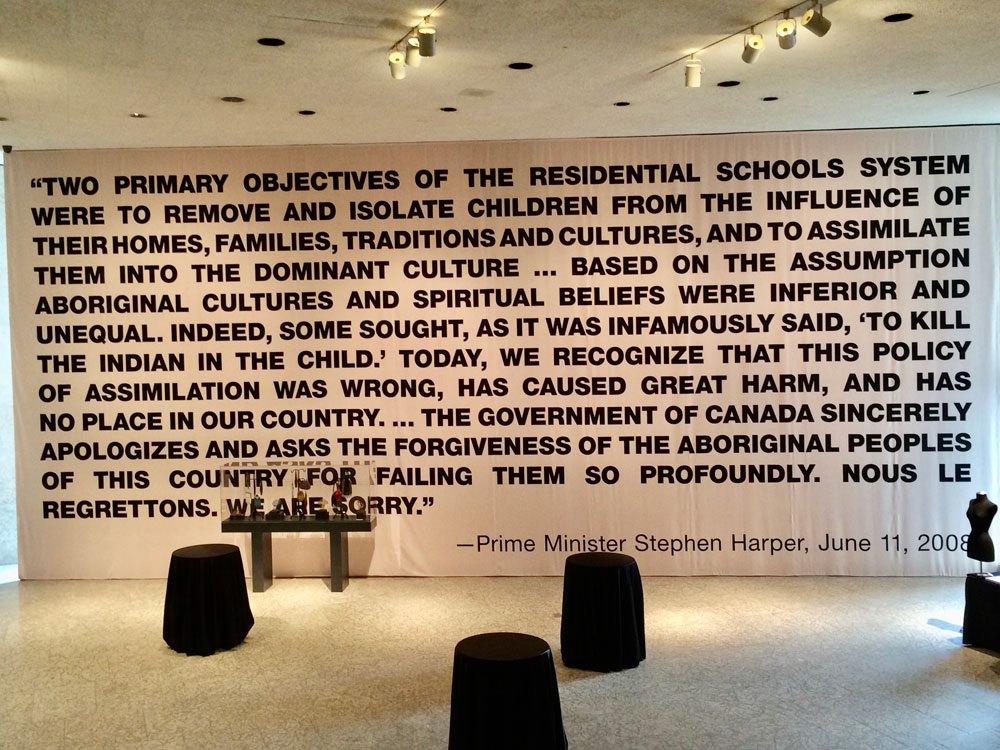

Americans are remarkably open to forgiving public figures who eventually publicly express their contrition. It goes to a famous statement of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.:

“We must develop and maintain the capacity to forgive. He who is devoid of the power to forgive is devoid of the power to love. There is some good in the worst of us and some evil in the best of us.”

To many, it is hard to forget or overlook the facts that Mam compelled young women to lie about their stories of abuse in order to impress international donors, or that Mortenson made up stories out of whole cloth about his personal adventures, or that Armstrong vilified his critics while defending himself against doping charges. However, it may well be that despite misgivings about their personal character and, in some cases, questions about the management of their nonprofits, American donors are willing to give clay-footed charitable icons second, third, and fourth chances.—Rick Cohen