October 12, 2020; Sports Illustrated and Daily Californian

As the viability of training and competition this year gets ever more doubtful, colleges and universities are cutting their sports teams at a rapid pace, leaving some students wondering what paths for their education and training will be left open to them. At Stanford, 11 programs have been cut, and seven are eliminated at George Washington. These programs typically include such things as wrestling, swimming, track, and tennis…in other words, not football. Emily Giambalvo of the Washington Post writes:

The novel coronavirus pandemic has financially strained athletic departments. Schools didn’t receive their usual distribution from the NCAA after the men’s basketball tournament was canceled. They have lost revenue from student fees and donations. Most conferences are playing a shortened football season, with limited or no fan attendance, hurting yet another revenue stream. Many smaller schools are no longer receiving the payouts from nonconference matchups against Power Five programs. Schools have responded to these deficits by eliminating teams.

These kinds of decisions can have far reaching effects, however.

Stanford has historically touted the athletic department’s vast array of varsity programs. Athletes with ties to the school have won 270 Olympic medals, so Stanford’s decision to cut 11 programs alarmed those invested in Olympic sports.

As a case in point, Minnesota’s Board of Regents voted three days ago to discontinue three teams by the end of this academic year. One of those is men’s gymnastics; this means the elimination of one of a few competitive collegiate teams at the national level, which harms the field.

Typically, athletes in men’s gymnastics come up through gyms, training intensively for many years while looking to gain a place on one of the Division I college teams in the hope they can move from there to international competition including the Olympics.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Minnesota athletics director Mark Coyle was asked by regent Michael D. Hsu how much the plan to cut these teams would save. “I believe that number will be $1.6 million,” Coyle responded.

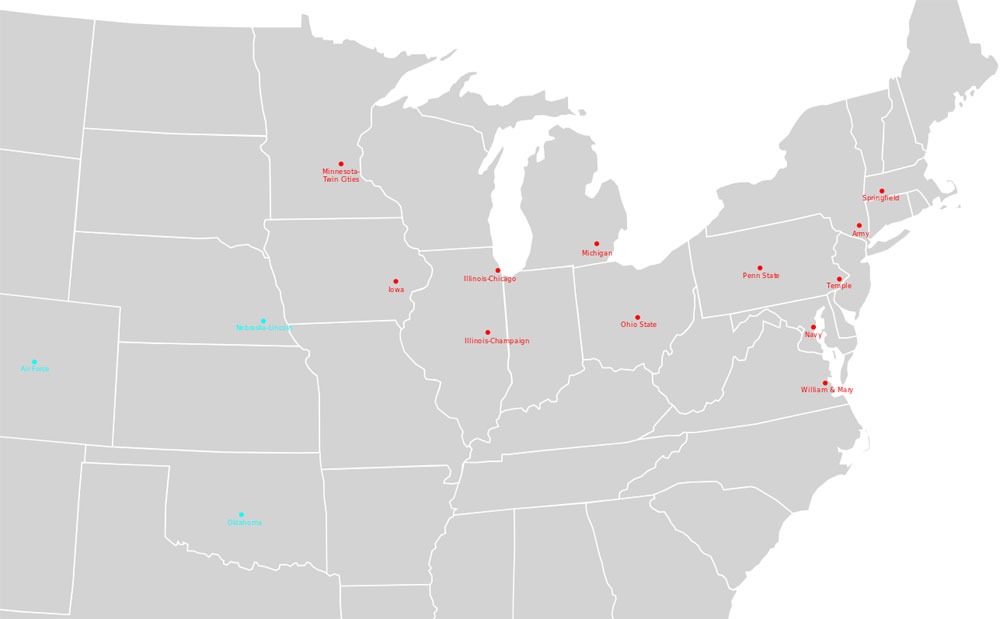

Men’s gymnastics programs in higher education institutions are already few and far between. Where there were more than 200 men’s gymnastics teams at colleges and universities in 1969, there are now only 14. With Iowa and William & Mary ending their programs, and Minnesota’s program on the chopping block due to the stresses of the pandemic, there might soon be only eleven.

The NCAA programs are one of the two main pipelines for the USA Olympic team, says Jason Woodnick, vice president of men’s gymnastics at USA Gymnastics. Male gymnasts, in fact, tend to peak and compete on the world stage later than women, which fits the mold for their development in collegiate programs.

Woodnick has been scenario-planning with others in the network. “So if NCAA programs are gone, or are going,” he says, “that changes our entire focus, our entire structure, and where does that new pipeline come from and how we can develop it.” In the short term, there’s a question about whether or not virtual meets are possible this year; in the long term, perhaps a reconstruction of the pipeline is needed, and there are a number of proposals floating around about that.

The Daily Californian quotes Daniel Ribeiro, vice president of the College Gymnastics Association and assistant head coach of men’s gymnastics at the University of Illinois, as saying, “I still have a true belief in my heart that what’s happening here is wrong. We are not a profit industry. So I am fighting both sides. While I’m fighting the system and trying to raise awareness, I am also working to fit the system at the same time.”

Meanwhile, the athletes themselves are faced with finding their own way forward in athletic fields that are in change mode. At Dartmouth, where both the men’s and women’s swim teams were cut, among a number of other sports, Connor LaMastra, who has been swimming since the age of five, was faced with the difficult decision about whether to stay or go. He eventually transferred to Northwestern.—Ruth McCambridge