February 4, 2015; Electronic Intifada

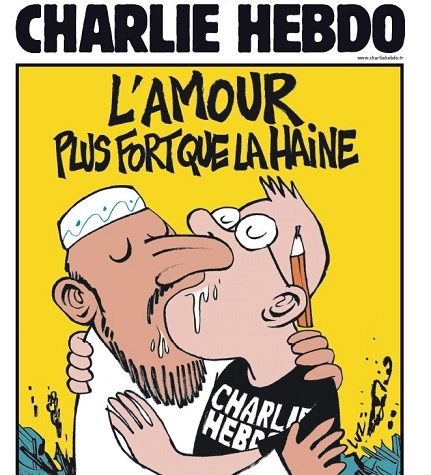

If being a journalist is dangerous in many parts of the world, being a cartoonist is worse in some ways, not to mention the risk of simply being killed by terrorists like the Charlie Hebdo staff. There’s something about political cartoons that make them particularly powerful. They hit you full on with one image and sometimes a caption. It doesn’t take much to get their import or for some people to misconstrue and misinterpret the message.

In the case of Palestinian cartoonist Mohammad Saba’aneh, the message is all too clear. Once jailed by the Israeli government for his cartoons, Saba’aneh is now under attack by Mahmoud Abbas and the Palestinian Authority for a cartoon that is alleged to depict the Prophet Muhammed—albeit, unlike the Hebdo cartoons, with a positive meaning and message. The cartoon was published, oddly enough, in a newspaper run by the Palestinian Authority itself, al-Hayat al-Jadida. Despite having marched in Paris with other international leaders against the killings of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists, Abbas initiated an investigation into the publication, called for “deterrent measures” against it, and demanded “respect for sacred religious symbols.” The newspaper says it has suspended the staff who were responsible for publishing the cartoon and conducted an “internal inquiry,” with the results passed along to Abbas himself.

Why such visceral and sometimes violent reactions to political cartoons? Many political cartoonists are aware of the power in what they do.

“Visual imagery is very powerful,” Kevin “Kal” Kallaugher, the longtime editorial cartoonist for the Economist once said. “Cartoons can be very effective. We are trying to make people think – using humor to deliver a message.”

The Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic artist and author of Maus, Art Spiegelman, explained the power of cartoons to Amy Goodman and Nermeen Shaikh of Democracy Now! in this way:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“Great cartoons…put…things in a high relief. And when they’re in a high relief, you can see them. You can then surround them with lots of words trying to contain them. But the images cut past all that. They move so directly into your brain that there’s no place to avoid them. They’re in there. Then you try to, like, put this salve around them, which is language. And that’s where we got that—whatever the currency rate has, a thousand words for each picture? Takes 10,000 words, because pictures keep leaking out in ways that weren’t intended even by the artist making it, but that are thereby functional—functioning as Rorschach tests for what actually are we living through right now.”

The editorial cartoonist for the Evansville Courier and Press, James McLeod, explained the role of cartoons in the Charlie Hebdo killings:

“I’m pretty sure there are probably hundreds of thousands of pieces of text out there that lampoon Islam and probably hundreds of thousands of visual images, Internet memes and so on, that are dismissive of Islam. But they don’t provoke much reaction. Cartoons, for some reason, have provoked this extreme reaction. Of all the things that these highly motivated, highly organized guys could have gone after, they went after a bunch of cartoonists. I think for me the attack illustrated once again the power of the cartoon, still, to have an enormous impact… Both sides of the equation, I think, were a testament to the enduring power of cartoons…. I think on one level we’re very visual [creatures]; we react to images. […] Political cartoons, I think, are maybe drawing on that, on something that’s almost hard-wired in us…”

Saba’aneh must clearly understand both sides of the equation, for sure. In 2013, he was jailed by Israeli occupation forces in the West Bank and held in detention for five months. The charge was that he had collaborated with Hamas, because some of his cartoons were included in a book by his brother, who happens to be a member of Hamas. Saba’aneh told the Israelis that he was collaborating with his brother, not with Hamas, and that Hamas actually hates him (due to a cartoon of his that criticized Hamas member Ismail Haniyeh, who had been a prime minister of the P.A.), but the Israeli government didn’t buy his explanation.

Now, Abbas has Saba’aneh under investigation for a cartoon that the cartoonist says doesn’t depict the Prophet, but an image of a “Muslim spreading the prophet’s positive message.” According to Ali Abunimah, the author of the article and co-founder of the Electronic Intifada (which has published Saba’aneh’s cartoons in the past), Saba’aneh “was motivated to make the picture because of the frequent denigration of the prophet not only in the French magazine Charlie Hebdo but in publications and websites around the world.”

Saba’aneh is hopeful that at the end of the day, Abbas will end up on the side of free expression. Having experienced a jail cell with the Israelis, he probably doesn’t look forward to a comparable experience with the Palestinian Authority. But he does face the challenge of many political cartoonists, whose production of visual images generates powerful reactions. Consider the Syrian political cartoonist Ali Farzat, current head of the Arab Cartoonists’ Association. After an exhibition several years ago of his cartoons satirizing various dictators, he received a death threat from the late Iraqi dictator, Saddam Hussein. Though he had his own independent publication for two years, government censorship shut him down. When he was critical of the Assad regime in Syria when the uprising started in 2011, according to a profile by the Human Rights Foundation, “masked gunmen assaulted Farzat and broke both of his hands and his fingers, in a clear message of intimidation and retaliation for his work.”

In the wake of the Charlie Hebdo killings, political cartoonists sometimes face great danger. It takes courage to produce powerful visual images, sometimes risking arrest and violence. We can only hope that Mahmoud Abbas’s walk through the streets of Paris on behalf of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists will inform his better judgment in the case of Mohammad Saba’aneh.—Rick Cohen