September 30, 2019; The Root and CNN

At the heart of the wrongful death lawsuit of Ismael Lopez is the question of just who is afforded Constitutional rights. According to the attorney for Southaven, Mississippi, who filed a motion to have the suit dismissed, Lopez has none. Why? Because when he was shot and killed by Southaven police, he was an undocumented immigrant.

As shocking as this argument might seem to some, there are many who would line up to support this concept—that the rights conveyed to “the people” in the US Constitution are limited in terms of just who gets them.

In the Lopez case, the drama plays from both sides. According to The Root, the police went to the wrong address to serve a warrant for domestic assault. When they arrived at Lopez’s mobile home, they did not announce themselves at the door, and Lopez died from a single gunshot wound to the head.

But the police, the city of Southaven, and their attorney claim Lopez was not a nice man, not worthy of citizenship, and therefore not entitled to any rights under our laws. The blame for his death lies squarely on his shoulders because of his prior conduct and actions—which, indeed, broke US laws. Lopez had been deported twice and reentered the country without permission, according to a report obtained by a Memphis paper, and he had an arrest record of domestic violence and DUI charges in Washington state in the 1990s. As one of the city’s attorneys wrote:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

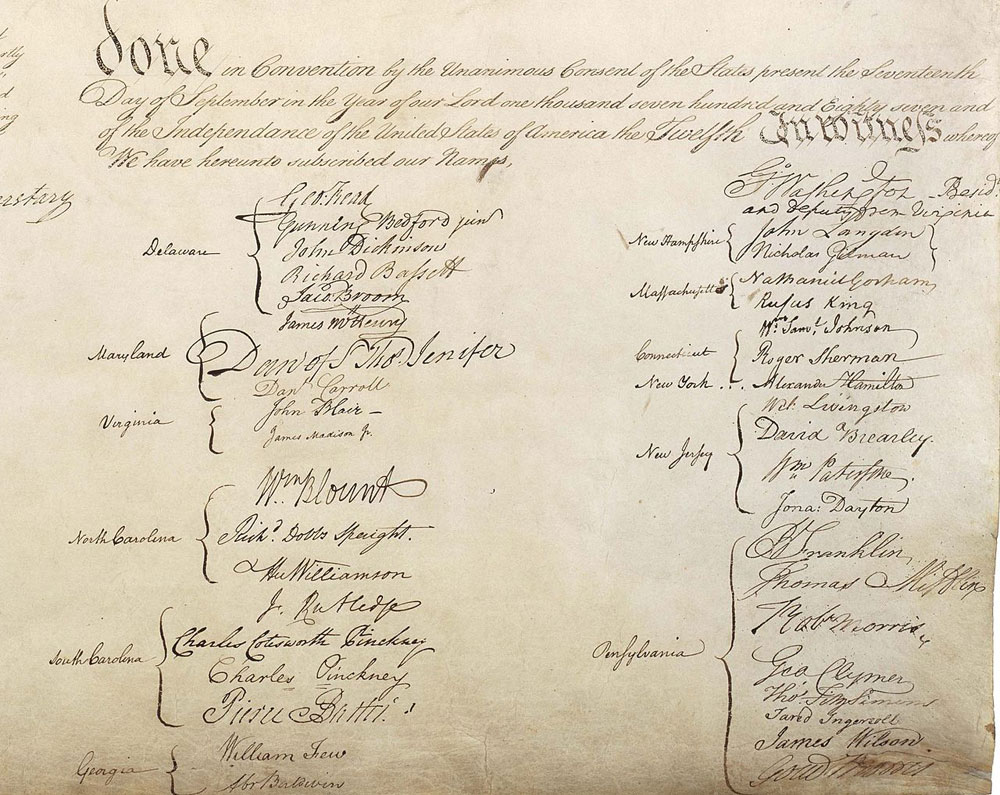

“If he ever had Fourth Amendment or Fourteenth Amendment civil rights, they were lost by his own conduct and misconduct. Ismael Lopez may have been a person on American soil, but he was not one of the ‘We, the People of the United States’ entitled to the civil rights invoked in this lawsuit,” a city attorney wrote in her motion.

In the conclusion, the city lawyer says, “Federal civil rights are not civil rewards for violating the laws of the United States.”

The Constitution, however, seems to say otherwise. It is hard to find the word “citizen” in the document. The writers much preferred the use of the more encompassing word “people,” which could encompass those who are documented and those who are not.

Being a non-citizen does not exempt you from the laws of a country, so it is hard to reconcile the logic (such as it is) of the Mississippi arguments. And there is case law, even Supreme Court decisions, that would uphold the rights of the Lopez family’s wrongful death suit. Often cited is the 1982 Plyler v. Doe decision that struck down a Texas law denying public education funds for children who were in the US illegally. The Supreme Court ruled that the statute violated the 14th Amendment of “equal protection of the laws.” There are many more lawsuits pending, based on the recent changes in immigration laws.

Much hangs in the balance here. There’s an alleged wrongful death at the hands of the police, who went to the wrong address and killed an undocumented immigrant. You have a cry for justice from his family and friends, and the response which followed from the authorities that his status and criminal background left him with no access to justice and no rights under our Constitution. The question posed of just who has constitutional rights in this country remains.—Carole Levine