February 4, 2020; Washington Post

Before HBO’s Watchmen put it in its premiere episode, not many people, including some residents of Tulsa where it took place, knew about this important piece of African-American history. But since we are in the middle of February, Black History Month, this is a good time to lift up the unseen drivers of the race dynamics and social disparities that persist in this country.

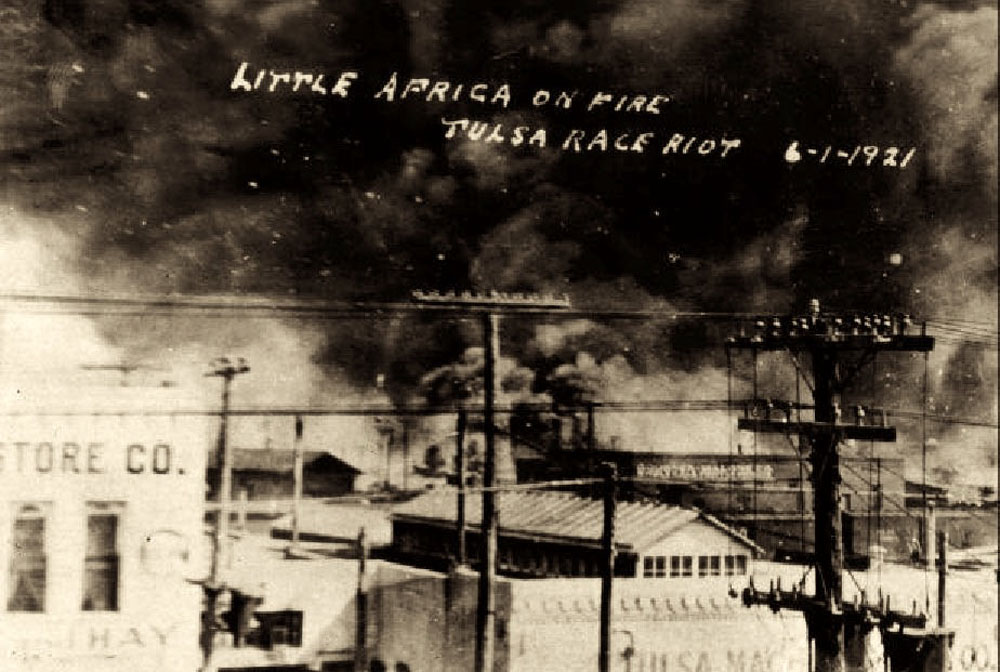

Forensic archaeologists, led by the Oklahoma Archaeological Survey at the University of Oklahoma, are on the search for possible graves where African American victims of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre were buried. During this two-day massacre, a white mob burned down multiple businesses and homes and killed more than 300 African Americans. Beginning in April, these archaeologists will investigate the Oaklawn cemetery where a “large anomaly” is believed to contain human remains. Machines will be used to remove the top layers of soil, and then the archaeologists will do the rest by hand.

“We do not propose to exhume any human remains during this phase,” said those leading the investigation. “However, any human remains that are uncovered during the excavation will be treated respectfully and with reverence.” Any remains found to be connected to the massacre, “will be further investigated by law enforcement and the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner.” The Mass Graves Public Oversight Committee, which includes community leaders, historians, scholars, and descendants of massacre victims, will decide on the steps to be taken when remains are recovered.

This search is happening after almost 20 years since the original search for the graves was closed. Tulsa mayor G.T. Bynum opened the investigation again because he believes the city should understand what happened before the massacre’s 100th anniversary next year.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The Tulsa race massacre started on May 30, 1921, when Dick Rowland walked into the Drexel Building, the only place in downtown with a restroom available for black people. As he stepped into an elevator, a white woman already inside started screaming. No one knows exactly what caused her to scream, but news broke out the next day, and Rowland was taken to the Tulsa courthouse after his arrest.

A mob assembled outside the courthouse, angry at Rowland for allegedly harming a white woman. So, too, did a group of black men who came to protect Rowland. Tensions grew, and shots were fired. The white mob marched to Greenwood Avenue, also known as “Black Wall Street,” and started attacking innocent people. The late Olivia Hooker, a massacre survivor who was only six years old at the time, still remembered the horror of that day. “It was quite a trauma to find out people hated you for your color,” she told the Washington Post, “It took me a long time to get over my nightmares.”

If this anger was over one man, why destroy a whole neighborhood? It all had to do with success. In her NPQ article last year titled “How Black Reparations Differs from a New Economic Rights Project,” Cyndi Suarez quotes Ta-Nehisi Coates when he said “political violence was visited upon blacks wantonly, with special treatment meted out toward black people of ambition.” That was exactly what happened on Black Wall Street. Local white residents resented the “upscale lifestyle African Americans were having in Tulsa.” They attacked with the knowledge that it would damage the community financially.

Also, as Suarez says in that same article, “the debt that the US owes black people is not simply financial, but social and psychological.” Successful businesses were burned down, and hundreds of families lost loved ones and friends all because of hatred from white people. Children like Olivia Hooker had to live through that time, and we are positive she wasn’t the only one who suffered from nightmares.

The search for these victims has taken too long, but we are glad their families might be able to get some closure before the 100th anniversary. NPQ will be following this story to learn if they will be able to find the remains of victims. We are also curious to see how these remains will be honored and commemorated.—Melissa Neptune