July 8, 2020, WBUR News

“We will never allow an angry mob to tear down our statues, erase our history, indoctrinate our children, or trample on our freedoms,” President Trump exclaimed to a crowd of supporters in front of Mt. Rushmore over the July 4th weekend. This speech was made while Native American protesters were being pepper-sprayed and told to “go home,” COVID-19 took over 129,000 American lives, and movements continue in the wake of the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and countless others.

Whether the president, his administration, and supporters disagree, there is a palpable reckoning of the nation’s history of structural racism occurring in the present. It’s clear the White House will not lead the movement towards national realignment, but policymakers, advocates, and local governments are looking at global experiences of reconciliation in order to act locally.

District attorneys in Boston, Philadelphia, and San Francisco announced early last week that their cities would form “Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commissions.” These commissions, fashioned similarly to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission within post-apartheid South Africa, would review racial inequities of police violence and misconduct within the legal system. The project will have the assistance of the Grassroots Law Project, and will hopefully be part of the process of garnering community trust to reimagine their relationship with the law.

Boston’s Suffolk County D.A., Rachael Rollins, states, “We’re going to ultimately reimagine what the interaction between law enforcement and certain communities can be and this is one way we’re doing that. We are going to do the hard work to document. To atone. And I believe that we’re going to move forward and be able to solve more homicides or get more involvement from communities because they’ll finally feel they’ve been respected and acknowledged.”

This is not the first domestic call for truth and reconciliation after the murder of George Floyd. Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA) proposed legislation for a nationwide establishment of a Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation (TRHT) commission that would investigate the effects of slavery, institutional racism, discrimination, and the nation’s unpacked history upon the present day. A broad coalition of supporting legislators and institutional leaders have backed the legislation, with Dr. Gail Christopher, executive director of the National Collaborative for Health Equity, stating, “NCHE believes that a TRHT Commission can help jettison the hierarchy of human value and launch a new era where all human beings are valued and have a capacity to see ourselves in one another.”

What would a Truth and Reconciliation Commission look like within the United States? Many experts believe true reconciliation occurs when two formerly hostile sides become respectful of each other, ideally leading to peace and even friendship. This can take the form of formal apologies, reparations, prosecutions, monument creations, and more.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

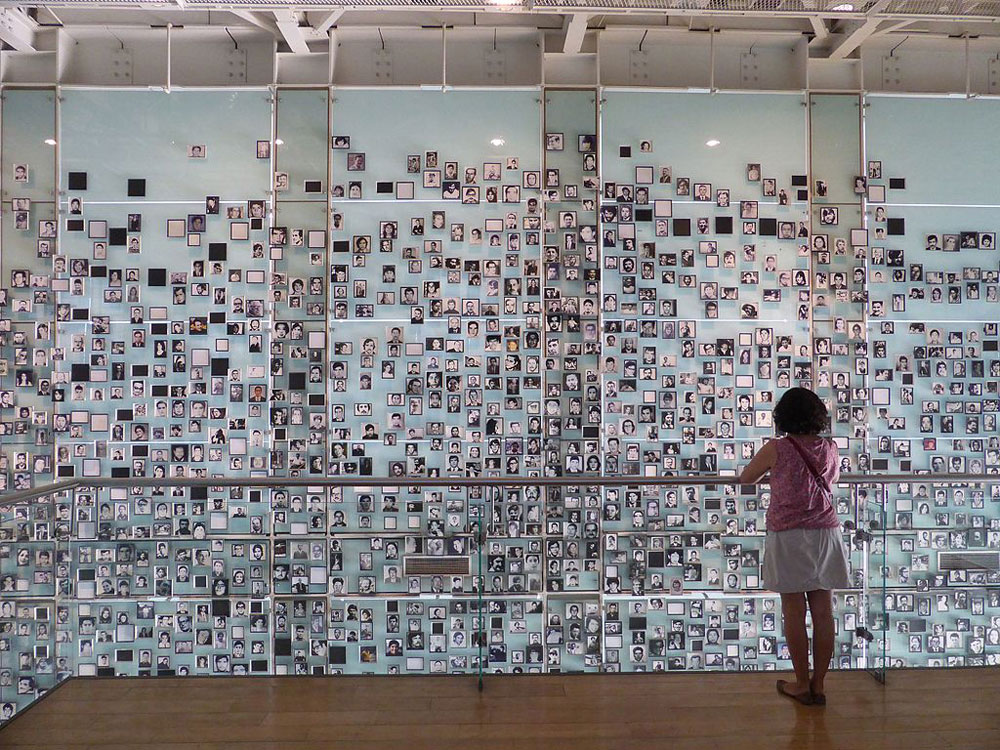

Many supporters look to the multi-year process started in 1995 post-apartheid South Africa. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission collected over 21,000 statements from victims of human rights violations, with much of the testimony broadcast nationally. The process was less of a post-WWII Nuremberg hunting down of perpetrators, but more of a talking through of grievances to try and heal historic divisions between the White and Black communities.

This took place within open forums where wrongs were disclosed, examined, and confronted through education—even prosecution in some cases. Compensation, or other forms of redress, were recommended in the seven-volume report of abuses under South African apartheid. Commissions such as these can reduce the likelihood of further violence, as well as provide large awareness campaigns within communities that were unaware of the depth of systemic issues affecting others.

Reconciliatory researchers mention that community reparations, such as funding for development programming, public spaces, hospitals, educational scholarships, and more, are effective concrete measures to spark the healing process. Reparations have made the national spotlight in the US with the proposal of HR40: Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act, sponsored by Texas Representative Sheila Jackson and the Congressional Black Caucus. Evanston, Illinois followed through with a reparations policy in 2019 with a municipal tax on marijuana products, with the three-percent tax creating a dedicated fund of $10 million to provide reparations for African Americans within the city.

However, commissions are far from a “magic bullet” for healing. If commissions are politically manipulated, don’t involve diverse perspectives, and lack concrete follow-up, what results can be a failure for durable reconciliation. Some critics of South Africa’s TRC called the process the “Kleenex Commission,” out of a feeling some offenders were seen to have gotten off too easily. Bishop Desmond Tutu even said the TRC left behind “unfinished business.” Similar dissatisfaction has been expressed with Guatemala’s Commission for Historical Clarification and Nigeria’s “Oputa Panel,” which had neither the public nor legislative buy-in to unpack violent histories. Rwanda’s extensive National Unity and Reconciliation Commission (NURC) was seen as more impactful because it worked in to memorialize victims while also having legal backing to hand out jail sentences, along with communal reconciliation.

Although South Africa has still not arrived at a truly reconciled present, what with the white minority still controlling massive parts of the economy and ongoing trends of political corruption, there are important lessons to take away on the truth-telling process.

“Our efforts at reform cannot only focus on police. Your district attorneys, state’s attorneys, and top prosecutors are failing you too,” Rollins recently tweeted. How far sentiments will investigate, and act upon is still unclear.

Laying bare hard truths can create stronger authentic foundations for reimagined policies, institutions, and cultural norms to prosper. This is not the first time the United States has been brought to a crossroads of either directly owning up to these damages or persistently disregarding them. Repeatedly ignoring these wrongs will continue to create real time dangers for Black and brown well-being in the present and across generations.—Chris Cannito