Throughout its history, the US has implemented federal infrastructure projects that have benefited certain communities while devastating others. During the colonial period, much of the nation’s early infrastructure facilitated trade and commerce for colonists, but it also exploited Indigenous civilizations. The $36 million Transcontinental Railroad project, begun in the 1860s, displaced millions of Indigenous people and destroyed their sacred lands. A century later, in the 1950s, the Interstate Highway System created an efficient mode of travel for some communities, but it also divided and razed other communities and exacerbated spatial segregation.1

At their core, the nation’s infrastructure projects have either reflected values of equity or the lack thereof. In this context, health equity is defined as the removal of “obstacles to health, such as poverty, discrimination, and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments, and health care.”2 Historically, health equity has not been at the center of decisions to build infrastructure in the US, exacerbating or creating social, economic, and political disparities, which can be observed in urban, suburban, and rural communities in every corner of the nation.

Despite past challenges, it is possible to build infrastructure that improves health equity. In 2009, for example, the federal government allocated $19 billion through the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) to improve and accelerate health information technology in the United States.3 More than a decade later, this digital infrastructure has proven instrumental in raising awareness of health inequities for people of color—in terms of both rates of infection and vaccination status—brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.[4]

Fortunately, with the newest iteration of federal infrastructure funding—the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) passed in November 2021—we have an opportunity to chart a new course and begin centering health equity where we build and restore infrastructure.

Implementing Health Equity Infrastructure

There are six main categories of infrastructure that the federal government is most interested in funding through IIJA: transportation, water, broadband, resiliency, energy, and legacy pollution. Although some of these categories do not appear to have an obvious connection to health equity, they all do. For instance, in the “water” category, addressing health equity could mean ensuring that poorer households have as much access to clean drinking water as wealthier households. The “resiliency” category could involve ensuring that experimentation with renewable energy solutions (such as constructing a dam for hydropower) in one area does not pollute or damage the ecological landscape of a neighboring area. Resources for navigating IIJA funding are increasingly available.5

The power to forge a more equitable future for all communities through infrastructure is largely in the hands of local, city, state, and tribal officials. But it also lies in the hands of community-based organizations, nonprofits, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who are stewards of the communities that IIJA funding is intended to serve. We should not underestimate the power of non-governmental organizations to direct federal funding towards projects that improve health equity, although the roles of these organizations differ from governmental entities in important ways. The main distinction is that NGOs are not always eligible for federal funding.

In general, many federal grants are available to state and local governments as well as community groups. Even individuals can occasionally receive federal grants for higher education and other pursuits.6 However, discretionary and formula funds specifically for IIJA are only available to government agencies. Private organizations cannot apply directly for this funding. Yet, grassroots community organizations are incredibly knowledgeable about what is happening on the ground in their communities and often hold a great deal of trust and respect in the community. For this reason, nonprofit organizations and NGOs are powerful gatekeepers, advancing projects that will improve health equity and advocating against projects that will not. They must have a role in guiding how this federal funding is spent.

The Power of Grassroots Organizations

Many communities across the country have already recognized the importance of grassroots organizations in making effective, equitable changes in the community. Among them are the members of the Healthy Regions Planning Exchange*, convened by the Regional Plan Association. The Planning Exchange is a nationwide partnership bringing together healthcare practitioners, planners, advocates, and community leaders from large metropolitan regions, mid-sized cities, and rural areas across the US to confront and redress health inequities in urban planning at a regional scale.

During the second phase of the Planning Exchange, participants from each region have collaborated to change their organizational infrastructure to create better health outcomes for residents.

- The Louisiana Fair Housing Action Center and Operation Restoration organized for legislative and administrative policies to improve housing access and health outcomes for people with criminal and eviction records. Their campaign resulted in the passage of a new state law that allows renters with eviction records to offer more context about their records during the application process if their evictions were related to a state or federally declared emergency, such as COVID-19 or a hurricane.

- In the New York metro region, Make the Road New York (MRNY) and the Regional Plan Association partnered to advocate for policies that promote housing security from a health and racial equity framework, centering undocumented people in available programs. This work has brought attention to the importance of legalizing accessory dwelling units (ADUs) and the right to Good Cause eviction in New York State.

- In the San Francisco Bay Area, SPUR and Urban Habitat supported advocacy to pass a regional employer parking fee to manage parking supply and fund transit and active transportation in under-resourced communities. Their Parking Census has created valuable new knowledge to inform parking policy decisions. This information was shared through a public program to discuss the project findings and policy recommendations.

- In Chicago, IL, the collective goal of the Chicago Department of Public Health, Illinois Public Health Institute, and Metropolitan Planning Council was to embed health equity as a value in city planning processes, specifically by operationalizing a health and racial equity lens as part of the We Will Chicago citywide plan. So far, the team has made great progress in pushing recommendations that take racial equity into account.

- The Multnomah County Department of Health convened public health and transportation officials to coordinate policy, strategy, and funding for safer street design and to reduce traffic fatalities, especially in communities of color. This work has strengthened relationships between public health and transportation agencies.

- In Pittsburgh, PA, Pittsburghers for Public Transit (PPT) and the Hill District Consensus Group researched and advocated for land use policies connected to transit improvements. Through this partnership, the groups won a long-standing campaign to divest from a private, autonomous shuttle project and have the city invest in affordable housing, sidewalks, and other community needs.

- Members of the Greater Buffalo Niagara Regional Transportation Council and LISC Buffalo advanced an equitable transit-oriented development process through internal organizational training around racial equity and meaningful partnerships with communities of color. The project so far has helped to strengthen relationships and collaboration between governmental agencies and the nonprofit community in and around the area of transportation planning.

- On the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation has developed a Regional Equity Initiative to create and implement a vision for addressing systemic poverty and eliminating health and economic disparities on the reservation. This work has a focus on women’s equality. The team is in the process of implementing their action plan with Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW), a nationwide movement bringing awareness and urgency to the thousands of unsolved cases of missing and murdered Native American women.

The latest research from the Planning Exchange, coordinated and authored by the Regional Plan Association in collaboration with Planning Exchange participants, strives to offer a how-to guide for centering health equity in infrastructure decisions. Investing in Infrastructure for Healthy Communities explores three case studies in Atlanta, GA, Rochester, NY, and the Umatilla Indian Reservation, OR, where organizations are leveraging federal resources to promote health equity by building soccer fields next to train stations, replacing a highway with housing and community assets, and expanding a rural bus network. The report connects each case study with the work of Planning Exchange participants who are striving to complete similar projects in Pittsburgh, PA, Multnomah, OR, and Pine Ridge, SD, respectively.

From Identifying to Fulfilling Community Needs

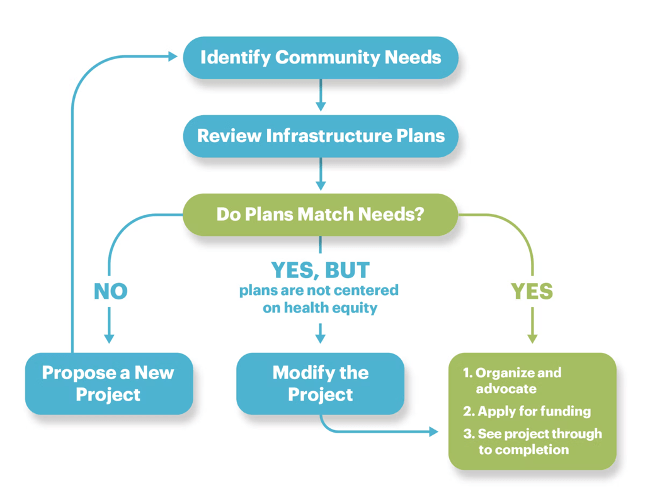

These six narratives illustrate that it is possible to build projects in the US with an eye towards health equity. The remainder of the report outlines in detail how other governmental and non-governmental organizations can follow in the footsteps of these organizations. The graphic below illustrates what the process can look like:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The first step is to identify community needs. Stakeholders need to consider the community’s characteristics and ask themselves: What sets the area apart from neighboring communities, for better and for worse? Given these disparities, what outcomes do we wish for the community? Do we want it to be a more accessible place? A more commercially vibrant place? A safer place?

The second step is to review existing infrastructure plans. It is important to know which projects are already in the pipeline so that we do not undo or unnecessarily duplicate projects. With this information, stakeholders can then answer the question posed in step three: Do the community’s plans match the community’s needs? Depending on the answer to this question, community representatives will either need to propose a new project that does match the community’s needs, modify an existing project to better match the community’s needs, or, ideally, move ahead and promote the existing project to make sure that community needs are fulfilled as promised.

While this strategy is highly recommended to begin building health equity, gaining trust, and healing past harms, it is easier said than done. Existing examples and case studies are crucial because they help illustrate the nuances of the process in different regions facing different health equity challenges. Some important lessons from the case studies that can be universally applied include the need to form, maintain, and leverage relationships; be creative; and persevere.

Both members of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and Pine Ridge Planning Exchange participants are working towards recapturing land for their people by building self-reliable transit and energy systems. For them, forming, maintaining, and leveraging relationships means being in touch with their communities’ values and building trust from the inside out. Rochester, NY, and Portland, OR, are exercising creativity by reframing and redefining the ways that highways are utilized to ensure that they are safe, accessible, child-friendly spaces. Finally, by gaining community trust and leading with community values, Atlanta, GA, and Pittsburgh, PA, have been able to implement novel or unconventional ideas, developing infrastructure projects that push back against the status quo when it comes to what transit-oriented development looks like.

These examples demonstrate that communities in many regions across the country are already envisioning a world where health equity dictates where and how infrastructure projects are constructed. This is one of the first steps toward building a more equitable society. This vision can only be realized, however, with federal buy-in and resources, including the IIJA funding that will be made available to localities over the next five to eight years. To accomplish this feat, it is critical that governmental and non-governmental organizations form and maintain partnerships with one another. It is equally important that community advocates are creative in their design of infrastructure projects to meet the needs of their constituents, and that they persevere and hold one another accountable until projects are completed. To achieve true health equity and help communities move forward, we must recognize and heal past harms. This process begins when a choice is made to prioritize health equity in everything that we do.

*Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) provided support for the Healthy Regions Planning Exchange. Views here do not necessarily reflect the views of Bloomberg Philanthropies or RWJF.

Notes

- Mohl, R. (2002). The Interstates and the Cities: Highways, Housing, and the Freeway Revolt. Poverty and Race Research Action Council.

- Braveman, P., Arkin, E., Orleans, T., Proctor, D., and Plough, A. (2017, May 1). What is Health Equity? Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2017/05/what-is-health-equity-.html

- The Commonwealth Fund. (2022). “Early Federal Action on Health Policy: The Impact on States.”

- Reavis, T. (2020, Dec 2). Prepared and Ready: America’s HIEs and the Response to COVID-19. Journal of Ahima.

- More information on the implementation of IIJA funding can be found by visiting the websites of the National Governors Association, the White House Briefing Room, the United States Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, and other agencies.

- Such opportunities can be browsed at Grants.gov.