Editors’ note: This is the second of two parts of this article, the first of which appeared in NPQ’s summer 2013 edition. The article started as a paper titled “Promoting Passion, Purpose, and Progress Online”; it was first published online by Alliance Magazine, in February 2013. This half of the article addresses the realm of effectiveness measurements, a much worked-over concern in the sector. Do we need a more consistent set of standards by which we all judge the work of nonprofits, and if so, what should it include as foci and questions to be answered? Schmidt here takes a very complex and diverse system and tries to overlay general scaffolding for evaluation of effectiveness. Does it resonate? Do you have thoughts to add?

The Nonprofit Management and Reporting System

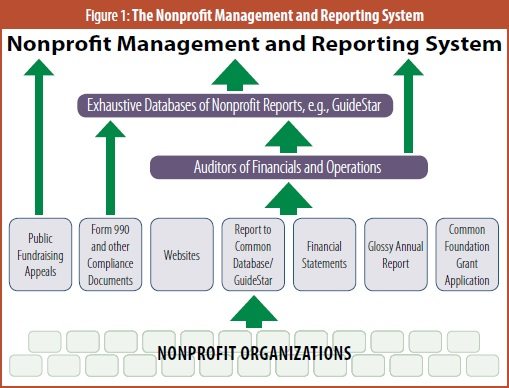

The nonprofit organization is the ultimate object of the attention of each system within the philanthropy ecosystem. As figure 1 illustrates, a reporting process that provides pertinent performance information to external stakeholders as well as to internal staff resides at the heart of each effective organization’s management process. In an ideal world, external audiences and internal organization actors would focus upon precisely the same information; the same objectives for output and outcomes, capacity development, and fiscal health and proper fiduciary conduct; and the same periodic reports that explain progress toward meeting those objectives. It is incumbent upon the trustees and senior management of nonprofit organizations as well as donors, transaction intermediaries, and evaluators to reinforce consistent reporting practices. If we are serious about realizing effective management practices at nonprofit organizations and working through them to achieve excellent results, we must all seek, review, and make decisions using the same managerial reports for past periods and plans for future periods.

To achieve that end, a common reporting core, such as that promoted by the Charting Impact initiative of Independent Sector, the Better Business Bureau (BBB), GuideStar USA, and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, should accompany all nonprofit reports. These critical questions, or a very similar set of reporting elements, are central to any useful planning, managing, and reporting system. In the spirit of common objective setting, rather than follow my own entrepreneurial inclinations to advance a new, proprietary set of questions, I will use Charting Impact’s model and five questions to make this point.1

- “What is your organization aiming to accomplish?” Charting Impact’s first question in essence asks the organization to state a vision for a distinct future (within a distinct time frame) that will result from successful completion of its work. This is the organization’s “intended impact.” It is also a question that must be revisited for relevance every reporting period, because it forms the essential rationale for the nonprofit and the cornerstone for its strategic plan. I would argue that the vision the organization offers should have external as well as internal characteristics: external with respect to what the organization’s good work will mean for society; internal with respect to what the organization will look like at that future “vision” date.

- “What are your strategies for making this happen?” Or, “What programs will you pursue to achieve this larger vision?” Or—maybe—“What is the organization’s theory about how it will achieve change (the intended impact)?”2

- “What are your organization’s capabilities for doing this?” This is the reality question, anathema to many a social entrepreneur. But an answer is essential for every serious effort, even if the answer indicates capabilities short of what’s required at the moment. A more useful construction might be, “What are your organization’s current resources and your plan to secure any additional resources and competencies required to achieve your objectives?” Ultimately, the resources and objectives must be reconciled, or, if not, objectives must be restated. This is an excellent exercise that must be conducted in one form or another each reporting period.

- “How will you know if your organization is making progress?” Though an important question, this requires some art to develop. It’s an unusual organization for which the actual “output” of its program activity will equal demonstrable progress toward the longer-term vision. With respect to tracking the organization’s progress against strategic objectives and toward achieving its vision, it is important to choose metrics that can be discerned easily and measured accurately; understood by staff and utilized in their own periodic internal reporting; and for which a reasonable case (theory of change) can be advanced for its correlation with the impact the organization intends to have.

- “What have and haven’t you accomplished so far?” The fifth and final question is the regular performance report. It must be emphasized that answers to at least one (and probably more than one) of the first four questions will change each reporting period. We should also expect the answer to question five to change, and when it does, the reasons for the change should be flagged and incorporated along with the progress statement in any reporting. Appreciation of these changes, regular restatement of answers to these questions, and faithful reporting of the results of the process are the hallmarks of a learning organization. Every participant in the philanthropy ecosystem must respect the central importance of this process.

Likewise, it is not enough for GuideStar USA, the Better Business Bureau, Independent Sector, and the Hewlett Foundation to commend the five questions to nonprofits as best practice. Nonprofit organizations’ answers to these questions must be thrust front and center in the information systems developed and displayed by each of these actors, by all other evaluators, and in the grant application and reporting forms required by all foundations, donor intermediaries, and other institutional philanthropists. Only then can we expect that the substance of the questions will be taken seriously and internalized in the sequential planning/ reporting/planning/reporting processes of each nonprofit.

In other words, the “audience” for the Charting Impact initiative must all be serious participants in the philanthropy ecosystem, and foremost among these are the nonprofit organizations themselves. Although the level of sophistication and quality that nonprofits bring to their reporting will vary considerably, every organization has ample opportunities to interject consistent responses to the five questions in every reporting venue.

What Is the Importance of This System within the Philanthropy Ecosystem?

To achieve its potential, the philanthropy ecosystem requires that nonprofit organizations operate and, just as importantly, report as effectively and consistently as possible. Without an expectation and fact of dependable reporting by nonprofits, the ecosystem will not move beyond its current dysfunction.

What Are the Bottlenecks or Impediments to Making This System Function Optimally?

The failure of the donors and intermediaries comprising the giving system to take nonprofit reporting seriously, agree on a common application for grants, and demand a common annual report that derives from the nonprofit’s internal planning/management/reporting process is the principal impediment to optimal functioning of the nonprofit management and reporting system. Unless nonprofits can count on donors to coordinate to reinforce the value of excellent and singular reporting, they cannot expect to benefit externally from consistent donor signals or internally from more effective management processes. Instead, they are more likely to spend scarce managerial time responding to multiple and disparate requests for information that may be impossible to internalize in any cohesive reporting system.

What Are the Principal Opportunities for the Innovative Social Entrepreneur?

We must do everything possible to focus the attention of donors and their intermediaries on the necessity for cohesion in the funding application and regular nonprofit reporting processes.

- Revisit the Charting Impact program. Redirect the promotion of the Charting Impact program from nonprofit organizations to donors and donor intermediaries. If every donor and intermediary demanded an annual report that featured the five questions, the quality of nonprofit reporting—and, as a consequence, philanthropy and nonprofit management—would improve immediately. Short of that, attempts to influence nonprofit reporting behavior will fail.

- Synchronize all standard nonprofit reporting systems. This opportunity will require social entrepreneurs to engage in a program of education and advocacy with established ecosystem reporting systems to reinforce the ethos of the Charting Impact program. For twelve years, GuideStar USA, the most ubiquitous and neutral reporting venue, has asked that nonprofits voluntarily enter answers to survey questions that are quite similar to Charting Impact’s. If GuideStar USA ensured that its own reporting form were precisely consistent with the five questions, and honored or featured the most faithful, multiyear nonprofit reporters, it would be an immediate boon to this movement. Additionally, even though the IRS recently revised its Form 990, it might be willing to include these questions in the next iteration if the principal ecosystem actors could converge around the five questions. The inclusion of these questions on the universal reporting form for all tax-exempt organizations would aid in the effort to create a common reporting formula benefiting nonprofits and the public in general. Further, associations of nonprofits could include the five questions in the best practices they promote to their members. Groups that honor the best annual reports could require that proper attention to the five questions become a central criterion for consideration. Finally, the principal nonprofit sector media could be trained to look for answers to the five questions in their reporting on individual nonprofits instead of focusing on financial ratios, as they do today.

- Use common foundation grant applications and annual reports. Any effort to cajole, coerce, or otherwise convince foundations to adopt common policies with respect to grant applications and subsequent evaluation of the performance of organizations would be well worth undertaking. To be meaningful, this would require that foundations first focus intently on the nonprofit organization as an entity rather than on its individual programs. Further, foundations should use the formal, annually revised business plan and annual report of each organization, both of which would emphasize the organization’s response to the five questions as its primary source of information about an organization. In this way, foundations would reinforce more effective internal management systems and strategic planning as well as pertinent reporting. They would also benefit from the receipt of better information and presumably more effective nonprofit interventions.

- Establish a service to audit nonprofit output/outcome reporting. The planning/management/reporting information environment envisioned here asks nonprofit organizations to self-report their accomplishments versus their objectives. Presumably, donors will identify organizations with work that coincides with their own purposes and values. In a well-functioning philanthropic ecosystem, both donors and nonprofits would have access to a robust philanthropy knowledge system, and donors would have the ability to reward organizations that pursue objectives that are most consistent with community goals and expert opinion about effective solutions. One concern would be how to determine whether the organization’s reported accomplishments are accurate. We rely now on accounting firms to audit the veracity of a nonprofit’s self-reported financial statements, and we can expect the development of firms that audit and validate reported organization accomplishments. Such developments would add appreciably to the integrity of the ecosystem.

The Nonprofit Evaluation System

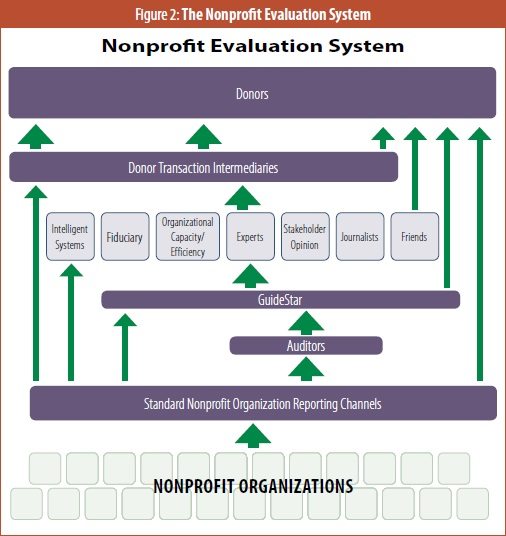

Figure 2 depicts the entire flow of information about nonprofit organizations reported directly and indirectly through intermediaries from nonprofits themselves as well as content-contributing intermediaries to donors and donor transaction intermediaries. Most nonprofit self-reporting is made through standard reporting channels.

Some nonprofit reporting, mostly promotional, finds its way directly to individual donors. Some of it, grant applications and performance reports, flows directly to foundation program staff. The financial statements of substantial organizations are audited by public accountants. Data flows directly to regulators (including the Form 990 to the IRS and state charity officials) and finds itself posted at neutral online data services, notably GuideStar. From these channels, data flow to third-party evaluators, and then, along with what is still a limited quantity of evaluative content, to donor transaction intermediaries and donors. The system comprises the evaluation methods and strategies shown in the middle of figure 2.

Evaluation Methods

Online initiatives promoting more generous or intelligent philanthropy seek to evaluate nonprofit organization worthiness from distinct points of view. It could well be argued that evaluation is as much a function of the evaluator’s values as it is of the substance of the organization’s work. Theoretically, there are as many ways to assess the worthiness of a nonprofit as there are evaluators or even donors. Seven evaluative methods, existing and theoretical, are covered below.

- Implementing intelligent systems. Intelligent systems recognize the pivotal importance of values and would enable individual donors to employ their own, using customizable evaluation algorithms and exhaustive data about the full population of nonprofits. There are no truly intelligent systems today, but with better data (maybe GuideStar x2) we could implement this intellectually attractive methodology.

- Assessing fiduciary and fiscal integrity. The BBB Wise Giving Alliance is an example of the second evaluative method, one largely concerned with fiduciary and fiscal integrity. It derives from the perceived need to protect the donor-consumer from fraudulent fundraising. This method does not address nonprofit operations and effectiveness.

Assessing organizational capacity/efficiency. Charity Navigator and periodic “best charities” lists focus upon the financial ratios of organizations as indicative of their efficiency, health, and capacity. While popular, this third approach lacks analytical integrity. Charity Navigator also evaluates organizations for accountability and transparency, and has recently announced analysis that will better reveal the impact made by organizations. The jury is out on this.

Assessing organizational capacity/efficiency. Charity Navigator and periodic “best charities” lists focus upon the financial ratios of organizations as indicative of their efficiency, health, and capacity. While popular, this third approach lacks analytical integrity. Charity Navigator also evaluates organizations for accountability and transparency, and has recently announced analysis that will better reveal the impact made by organizations. The jury is out on this.- Asking experts. Asking “expert” practitioners, academics, and funders to review the bona fides and work of organizations has significant inherent appeal. Philanthropedia seeks to assemble a body of informed opinion to help donors identify the most effective nonprofit organizations.

- Asking other stakeholders. Beyond seeking the point of view of external experts about the worthiness of an organization, is it not equally valid to seek and display input of other stakeholders of an organization—staff, beneficiaries, donors, etc.? Keystone Accountability has pressed donors and evaluators to adopt this fifth methodology. GreatNonprofits seeks to capture broad stakeholder sentiment about nonprofits.

- Journalists. Journalists have long been the principal public evaluators of nonprofits. Their evaluative method typically focuses on organization attributes the journalist deems “newsworthy.” We would be wise to remember the power of journalists and seek to advance their knowledge and sophistication accordingly.

- Friends. Friends have always been the most important implicit evaluators of nonprofits. Traditional philanthropy counts on the human tendency to share interests and preferences. Social network philanthropy initiatives are betting that reliance on friends will become ubiquitous on Facebook. Hopefully, these initiatives will bring objective system knowledge as well to this crowded venue.

What Is the Importance of This System within the Philanthropy Ecosystem?

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Theoretically, using intelligent systems, donors will one day manipulate data and generate their own custom evaluations of nonprofits. Even if this expectation is realized, we will doubtless witness increasing demand for third-party evaluations of nonprofit organizations. If these evaluators can reinforce proper and consistent nonprofit reporting (for example, the five questions), are transparent in revealing their own values, and contribute insight as well as adopt a cohesive philanthropy knowledge system, they will be an important and progressive component of the ecosystem. In fact, we need many more evaluators bringing many more perspectives and transparent values to this work. However, if evaluators encourage perverse economic behaviors by organizations (via overemphasis on financial ratios, for instance), erode the sophistication of donors by dwelling on irrelevant measures of worthiness, or let their perceived need for scale compromise the quality of their work product, they will be detrimental to the ecosystem.

What Are the Bottlenecks or Impediments to Making This System Function Optimally?

Perhaps the principal impediment to making this system function optimally is the failure of its practitioners to understand the practices, deficiencies, opportunities, and interconnectedness of the components and systems within the philanthropy ecosystem. Internet entrepreneurs are driven by a perceived need to achieve scale. When an Internet entrepreneur thinks about evaluating nonprofits, the first question faced is, “How can I evaluate large numbers of organizations so that I have sufficient scale to get noticed and influence behavior?” The inevitable result is the selection of highly “leverageable” methodologies (e.g., simple financial ratios, networked friends’ endorsements, Zagat-inspired stakeholder opinion, and wiki-like networks of experts), each purporting to be the most useful means of assessing nonprofit worthiness. Underscoring and encouraging this phenomenon, though, is the absence of more pertinent and readily available information about nonprofits and the environment in which they function, such as that envisioned within the philanthropy ecosystem.

Another barrier is the absence among evaluation practitioners of a clear understanding that this is not an ordinary sector to remediate like banking, book selling, music, or rummage sales. There is no first-mover advantage. This is no zero-sum game. There is nothing to lose and everything to gain through close collaboration among evaluators, helping new ones get started (especially ones with different methodologies), contributing to a common knowledge base, and reinforcing excellent nonprofit reporting practice.

A final barrier is reputational. It is easy for nonprofits and serious donors to discount the current work product of evaluators, particularly the online variety. The misconceived shortcuts taken by a few can hinder progress for everyone in this space.

What Are the Principal Opportunities for Innovative Social Entrepreneurs?

- The evaluator network. Serious evaluators should form an association to ensure high analytical standards (and encourage reinforcement of the five questions); identify opportunities in the evaluation space; attract others to the field; classify the association members by expertise (for those who specialize in nonprofit subsectors) and type of evaluation; and promote their work product through a common web interface. GuideStar USA could provide the most logical venue and organizing device for this service. It already has a head start through its relations with several online evaluators, although its recent merger with two evaluation agencies may compromise either its neutrality or the appearance of its neutrality in this regard.

- New knowledge/reporting-based evaluation algorithms. This approach would reconcile information from the philanthropy knowledge system and nonprofit management/reporting systems. From the knowledge system it would capture information about the most effective intervention strategies and community objectives. From consistent nonprofit reports (featuring answers to the five questions) and audited financial and output/outcome reports, it would capture information about the capacity and success organizations have in achieving their stated objectives. The resulting evaluative report would use the combined information to assess the extent to which an organization (1) established interventions and objectives based upon well-supported assumptions about the correlation of its expected operating outputs and community-valued outcomes, and (2) performed the stipulated interventions and achieved the stated outcomes.

- Establish a service to audit nonprofit output/outcome reporting. This opportunity was presented in conjunction with the nonprofit management and reporting system described early on in this article. Its inclusion here in the third-party evaluation section underscores the overlapping quality of these systems. But repetition is warranted in this case. The same energy that is now expended by an “evaluator” could very productively be devoted to verifying the programmatic representations of nonprofits. It would provide the philanthropy ecosystem with information of greater integrity, and reinforce conducive and consistent nonprofit reporting methods (the five questions again).

The Philanthropy Ecosystem

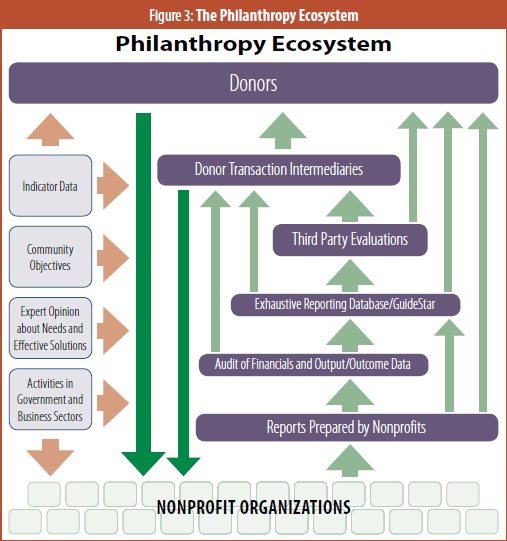

With vibrant subsystems each functioning well within the overarching ecosystem, we cannot help but enjoy more satisfying philanthropy, greater innovation, and better societal outcomes. As figure 3 describes, in this high-functioning philanthropy ecosystem, we will:

- Work from a common knowledge base;

- Seek consensus around community objectives and collective action;

- Require consistent reporting by nonprofits that is at once internally valuable for the organization and publicly transparent;

- Direct resources to organizations that do well the work society values; and

- Demand accountability not only of foundations, trusts, and intermediaries but also of ourselves—the vast population of individual donors who account for the great majority of charitable giving. As we build this ecosystem, we will introduce dependable market signals, establish consistent expectations, and instill dynamics that not only ensure mutually reinforcing progress but also demand and reward far greater innovation, online and otherwise, than we have witnessed to date.3

Conclusion

The positive implications of a highfunctioning philanthropy ecosystem are substantial. The success of the whole, as well as the success of each of the parts, requires successful innovation throughout. While expansive, the scenario developed here is hardly revolutionary.4 Rather, each component system described in this paper should be immediately recognizable. All of the ecosystem’s existing institutions will continue to play major roles. No legal or regulatory changes are proposed. Innovation and change will be evident at the edges; in the connective tissue linking people, institutions, and subsystems; and in greater accountability and a stronger ethos of common objective setting and collective action.

The frustrations encountered by today’s online social entrepreneurs will continue so long as we fail to recognize the systemic nature of the philanthropy universe and the need to embrace innovation throughout. We cannot blame nonprofits for being unaccountable if donors are inconsistent and unaccountable themselves. We cannot expect great results if the major players will not coalesce around common objectives and collective action. We cannot expect the success of innovative efforts by individuals to promote excellent philanthropy online if the rest of the philanthropy ecosystem is not functioning sensibly.

Finally, as we take on this surfeit of entrepreneurial challenges, we must remember why we are doing it. We do it to secure better outcomes for the causes we care about. We do it to build a stronger civil society and more competent and resilient nonprofit organizations. We do it to make safe the proposition that private initiative for the public good remains an essential facet of our democratic society. Narrow and “siloed” thinking as well as protection of turf, methods, brands, and the like have no place here. Instead, we must recognize this universe for what it is, embrace a common vision for a high-functioning philanthropy ecosystem, and set out together to build and link the components of that ecosystem. Only then will our frustrations dissipate and our ambitions ignite.

Notes

- For Charting Impact’s five questions, see www.guidestar.org/rxg/update-nonprofitreport/charting-impact.aspx.

- The Bridgespan Group may be the principal proponent of a planning/reporting language that places “intended impact” and “theory of change” at the heart of a good organization’s strategic plan.

- Today, it makes good sense to focus our attention on developing the philanthropy ecosystem as described herein. Nonetheless, it will soon be necessary to incorporate two other emerging systems into any future analysis (the online social entrepreneurs will make sure that this happens). One, the social network system, is shaping behavior in myriad ways. At a minimum, the Facebook and Twitter duopoly has become an essential venue for nonprofit organizations and a source of “friend-based evaluation.” The jury is out concerning the degree to which the ad hoc actions and associations of online social networks will supplant many activities and associations traditionally conducted and enabled by nonprofit organizations.

Likewise, a second emerging system, the social enterprise system, is capturing significant mindshare from a broad swath of society. Among its captives are many already committed professionally to the philanthropic ecosystem. What are the limits of this system? Can it realistically challenge the provenance of nonprofit organizations in our conception of a social action marketplace and in the hearts of donors? How can we most productively think about these developments?

For the sake of simplicity, I have avoided consideration of the extensive system of volunteer activity. Suffice it to say that implications of improvements of the philanthropy ecosystem that improve the participation, sophistication, and satisfaction of individual donors should hold true for volunteers as well. - A revolutionary solution might scrap the private foundation model for one less inherently autonomous and disconnected. It might scrap tax deductibility of organizations that operate in areas of dubious social benefit or simply don’t need the money. It might require accelerated payouts to defray the social cost incurred when foundations warehouse capital perpetually.

Buzz Schmidt is a visiting scholar at the Tuck School of Business, Dartmouth College. He is the founder of GuideStar and GuideStar International, the chair of the F. B. Heron Foundation, and a member of the boards of TechSoup Global and the Institute for Philanthropy.