“But what were you doing before?”

A young man, standing at the back of a lecture hall in Michigan, posed this question after a presentation I made in 2011 when I was president of the Heron Foundation. I was explaining with gusto that Heron was aligning all its assets—100 percent of endowment capital—with its anti-poverty mission.

But he was unimpressed. He thought he was coming to hear about “cutting-edge philanthropy.” And he learned that until recently, our supposedly innovative foundation wasn’t even doing what he thought all foundations already did: directing all their financial capital toward their missions.

And if I had shared more, I likely would have impressed him even less. He would have learned that Heron was and has remained an outlier for 25 years,1 and that the core business of endowed foundations is not mission-oriented; it is conventional investment management. And he would also have learned that foundations pay chief investment officers on average three times what chief executives make in salary, benefits, and bonuses.2

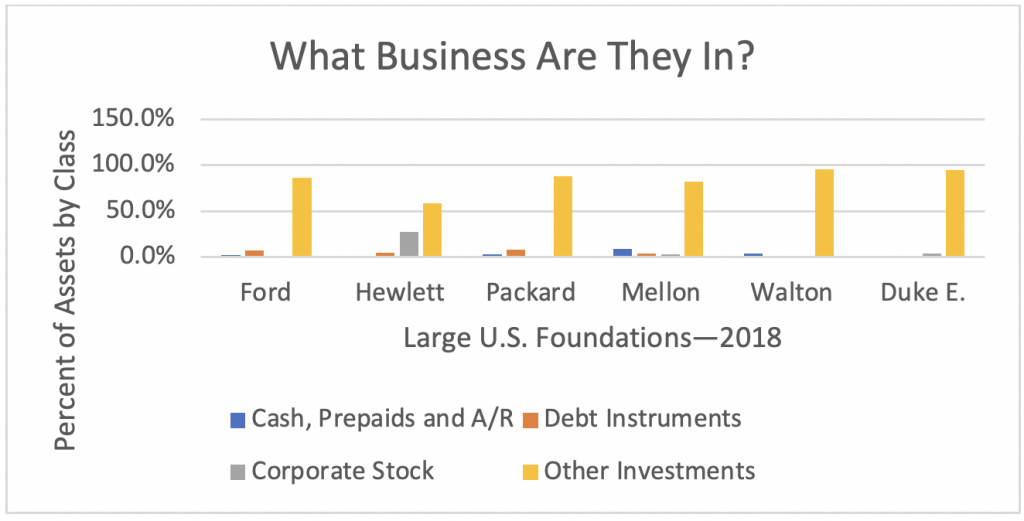

A graph of the asset composition of six large foundations reveals that from the point of view of capital structure, they resemble the business model of hedge funds, typically allocating 80 to 90 percent of assets to opaque, “alternative” holdings—private equity, distressed debt, partnerships organized in tax havens such as the Cayman Islands and similar. They have relatively small investments in either public companies or government.

Foundation boards’ usual justification for ignoring the mission-related impact of their investments is that only the maximum risk-adjusted returns available from a hedge fund-style business model make spending on grants—and therefore tax compliance—possible. In practice, foundations’ operating model and culture reinforces the notion, both within philanthropy and externally, that giving grants to nonprofits is the best and only tool for reaching philanthropic goals.

Most investment advisors, foundation boards, and grants officers believe that if an investment portfolio is aligned with mission, then poor financial performance will inevitably follow. But this idea of “either profits or purpose” is a false dichotomy. The interplay of varied time horizons, market vagaries, financially material “externalities,” unforeseen risk, and myriad other factors makes predicting returns far more complex than an either/or reckoning would imply.

At the very least, endowed charitable foundations, whose fiduciary duty of obedience to mission requires them to avoid investments that undermine their charitable work, should be working to do no harm. Ideally, they should do much more.

Here’s one example of “systems in need of change,” as MacKenzie Scott recently put it, at work.

Ford Foundation/JPMorgan: Collaboration on the Margins

In 2012, shortly after joining Heron, I attended a meeting at the Ford Foundation, convened by Darren Walker (then a senior executive, but not yet president) and community development bankers from JPMorgan Chase. Ford and JPMorgan were joining forces to go to bat for a Latinx community development financial institution (CDFI) in Los Angeles.

The CDFI had loans to homeowners totaling around $12 million in an L.A. neighborhood and hoped to nearly double its capacity by raising program-related investments (PRIs) of $10 million. The resulting fund would then top out at around $22 million.

Ford and JPMorgan were chipping in $1 million apiece in low-interest, long-term loans and hoped to help the CDFI raise the rest of the $10 million from prospects in the room. Those assembled included representatives of foundations working against poverty and homelessness such as Heron, Kresge, MacArthur, Casey, and Surdna. Such convenings aim to create “scale” by inviting collaboration to take on big challenges.

The CDFI’s neighborhood had been plagued by foreclosures. Muscular financial forces were working against them. The CEO of the CDFI mentioned one in particular: Colony Capital, a large private equity firm. Colony was rapidly acquiring foreclosed properties and either evicting the resident-owners or making them tenants.

To Colony and its investors, acquiring the foreclosed properties was a simple market opportunity. And to Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Reserve, the practice was seen as a means to fast-track the acquisition of a large backlog of distressed properties. This would remove these non-performing assets from large banks’ balance sheets so the banks could function again.

But to the people going through foreclosure, the process was crushing. For them and many others, the financial crisis marked the largest stripping of assets from working class and BIPOC communities in US history.

The CEO of the CDFI detailed the damage. After he spoke, both Walker and the JPMorgan banker cohost spoke in support. Every foundation executive in the room wanted to participate. I was no different.

Going to Bat for Economic Justice with Blended Finance

“We’re in!” I thought, applauding with the rest of the room. Later, I began to invent a sales pitch to our board in my mind, playing devil’s advocate with myself.

“Now, this CDFI has a loan fund of $12 million today, correct? JP and Ford are each in for $1 million. If eight more of us each lend them $1 million—long term and at low interest (in PRIs)— they will have a $22 million fund, mainly funded via debt from foundations and banks.”

My internal dialogue went on, this time with board members challenging me. “OK, but they’re bidding in this federal auction against a $30 billion private equity firm that is making cash-only offers on those properties and then turning them into rentals. Do we have a chance?”

And there was more. My imaginary board member moved in for the kill.

“Let me get this right. Here is JPMorgan Chase, a $2.3 trillion [then, now it’s $3.7 trillion] financial institution. And it’s working alongside a room full of foundations whose endowments together likely total around $20 billion. And together, you are trying to engineer a comparatively tiny Rube Goldberg of a ten-transaction, complex shared loan to a small CDFI to bid against the private equity firm? And you genius foundations and a mega-money-center bank think this is the best and quickest way to help homeowners in their neighborhood? Seriously, does JPMorgan really need help from foundations to de-risk a one-million-dollar loan?”

At the close of the Ford meeting, we had leapt to our feet applauding (myself included). I hadn’t yet thought of the obvious disconnect.

Why didn’t I figure it out and speak up then? At that point, I was a new president at somebody else’s meeting, and the CDFI leader was pinning his hopes on the solution he had presented. I didn’t want to be the skunk at his garden party. We all need allies, and these would be mine as well as his. Had I missed something? My imaginary board member seemed to be nodding.

The problem—and an alternative solution—began to seem both clear and unthinkable. Wouldn’t it be more effective (and straightforward) for the foundations and bank to organize their combined financial and social capital—possibly bring in some allies, even leveraging board members’ networks—and simultaneously help the CDFI and negotiate with Colony? What if the foundations thought of both their endowment assets and grants as being available for mission? What if banks stopped financing these activities by Colony and similar actors, and Fannie Mae stopped guaranteeing this debt? At any rate, why didn’t JPMorgan get involved in fixing this problem, or at least not contributing to it, if it was serious about its community development goals?

The whole Ford/JPMorgan/foundation exercise began to seem like a Kabuki drama. Both the big company and the big foundation were addressing this problem at the margins, without mobilizing the full power of their core businesses.

Serving the National Interest? Or Dabbling on the Margins?

Perhaps this tradeoff in government, corporate, and foundation policy could be justified by the exigency of the moment. Was this a time when speed and efficiency for the greatest number trumped all?

Alana Semuels, writing for The Atlantic, described it this way:

In 2010, at the height of the foreclosure crisis, the federal government watched nervously as hundreds of thousands of families lost their homes…. Without some kind of intervention, federal officials worried, the housing market would continue in its free fall.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

[…]

So the government incentivized Wall Street to step in. In early 2012, it launched a pilot program that allowed private investors to easily purchase foreclosed homes by the hundreds from the government agency Fannie Mae. These new owners would then rent out the homes, creating more housing in areas heavily hit by foreclosures.

[…]

It worked. Between 2011 and 2017, some of the world’s largest private-equity groups and hedge funds, as well as other large investors, spent a combined $36 billion on more than 200,000 homes in ailing markets across the country.

One could say that at least the homes and banks were preserved. Maybe this seemingly rapacious policy was necessary to avoid more damage.

Yet over the years, a new status quo prevailed. Fannie Mae drifted farther away from its mission, carrying on as a guarantor of debt for private equity investors. This allowed firms like Colony, Blackstone, and Cerberus to convert foreclosed homes into rentals, and in the bargain, build a market led by a few national mega-landlords.

The new landlords reportedly boosted profits by reducing services to renters while raising rents, creating a wave of evictions. A 2016 research paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta noted, “[an] analysis identifies large private equity investors and finds that some firms have uniquely high eviction rates. Some of the largest firms file eviction notices on a third of their properties in a year and have an 18 percent higher housing instability rate even after controlling for property and neighborhood characteristics.”

The rescued banks were willing participants. As the demands of the financial crisis ebbed, allowing banks to take stock and internalize lessons, did the “community development” side of JPMorgan interact with the business side to address the damage? Did they take a moment to see how they together might improve the odds of at-risk or disinvested homeowners? Not exactly. JPMorgan and other large banks continued, with government help, to finance these practices.

Hence our trouble in paradigm. The “trouble” is easy to spot. The paradigm, intentionally or not, is less visible. Its rules and customs guide investment decisions and corporate behavior in a way that disregards so-called “externalities” in the form of social and environmental costs, and in many instances, takes advantage of government and even charitable foundation subsidies and capital to accelerate them.

Are Things Changing?

Maybe today, a decade later, amid skyrocketing wealth inequality and a racial justice uprising, things can change. Leaders in both foundations and banks are certainly talking that talk. In August 2019, JPMorgan Chase’s chairman Jamie Dimon, speaking as chair of the Business Roundtable, noted, “The American dream is alive, but fraying.… Major employers are investing in their workers and communities because they know it is the only way to be successful over the long term.”

And, in October 2020, JPMorgan committed $30 billion to advance racial equity with Black and Latinx home ownership first on its list. Was this new? Not really. Back at that 2011 meeting at Ford, JPMorgan professed similar goals.

But what does performance tell us that promises and policies do not? JPMorgan continues to be among Colony’s and its parent companies’ lead bankers. And JPMorgan isn’t the only large institution whose public face is at odds with its core business operations.

Are foundations and CDFIs chumps—not the champs they like to think they are? With one exception, the large foundations in the room back in 2011—all with strong housing and community development programs—have maintained or increased their investments in opaque “alternative assets” as of the end of fiscal-year 2018, apparently without regard for mission. Many likely invest in the securitized products of Colony/Invitation or its parent, the private equity firm known as the Blackstone Group.

The point is not that this model is intentionally harmful to communities, or that there might not be some social positives in the “alternative” asset class. The point is that large holdings of alternatives that fund these kinds of activities call into question a charitable foundation’s, as well as a major bank’s, fundamental business behavior. No amount of grantmaking or lending through CDFIs, or public commitments to provide capital, can possibly succeed against these odds or paper over the fundamental damage done. The paradigm—the operating model, asset allocation, and culture—that segregates a foundation’s core investing business from its more marginal philanthropic operation must be integrated, or real progress, too, will be unattainable.

What Will Bring About Real Change?

Inequality’s roots as expressed in philanthropy’s business model have not been lost on Darren Walker, the organizer of the meeting back in 2011. Since becoming its president in 2013, he has worked to guide the Ford Foundation toward aligning grantmaking and its broader investments with the foundation’s global justice goals.

Walker has helped shift practices at Ford—no small task given the institution’s size and complexity. He and the board agreed to a carve-out of $1 billion (not integrated with the endowment of the foundation) that would be dedicated by Ford to program-related and mission-related investments. But there are roadblocks to full integration.

Those on the inside report consistent passive resistance. Even beyond the investment management staff, change is threatening to program officers, even when the goal is social change. Most program officers have bought into the narrative that financial returns will diminish if investments are aligned to program goals, and they fear reduction in their grant budgets. And they have little interest in acknowledging that the source of the grants they make to nonprofits to reform unfair financial practices, for example, includes the financial returns from predatory lenders, or that revenue from investments in fossil fuel projects may fund climate justice grantmaking, to name just two examples.

From my point of view, Walker is pushing ahead as fast as institutional complexities—and his board—will let him. But the board has a way to go to return to its creative, pathbreaking standard set over 50 years ago, back in 1968. That year, the Ford Foundation’s annual report noted:

In a major departure from past policy, the foundation this year began using part of its investment portfolio directly for social purposes. In the past, the Foundation has worked mainly through outright grants to nonprofit institutions. It will now also devote a part of its investment portfolio (through such devices as guarantees, stock purchases, and loans) to assist organizations, profit-making as well as nonprofit if necessary, working toward solution of social and economic problems of national concern.

Ford’s vision then, described as “a major departure from past policy,” seems like common sense today. But an approach that integrates giving, investing, influencing, and other powerful activities that could credibly address root causes in the larger economy has taken a back seat to the needs of money managers, as foundation assets continue to be effectively insulated from its mission, often undermining grantees and programs.

Can Philanthropy Lead, Not Lag?

The “sell-by” date on the paradigm dictating social and financial segregation in any business model has passed. In the immortal words of Walt Kelly’s cartoon character Pogo, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.” The trouble in paradigm goes beyond philanthropy to encompass business, the economy, and our own behavior.

This brings us to a stark reckoning. We are no longer in a world where harm and risk can be continually whisked away by ignoring them. Deals that drive high social and environmental costs—such as predatory lending followed by mass purchases of foreclosed homes for rental, or large carbon-positive extraction projects—threaten not only companies’ long-term value, but the livelihoods and survival of communities. That could be bad for business. As a Wall Street banker once said to me, “Who cares about the markets if everybody’s dead?”

Clearly, change is required. It is particularly troubling if foundations, while making grants and PRIs to CDFIs, healthcare programs, climate advocacy organizations, and similar, turn a blind eye to investments that undermine these efforts. The current segregated model enables this complicity, giving rise to social harm, undermining long-term market integrity, and contributing to systemic risk.

Foundation boards must act now. Here are four straightforward steps:

- Stop undermining grantees’ goals by investing in companies that work against them. Examine holdings with, at minimum, reducing harm in mind. Team up program leadership with investment managers to look for opportunities to shift investment or advocate where companies work at cross purposes to grantee goals. Grants to nonprofits alone can’t possibly compete, so don’t pretend.

- Add ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) performance to the compensation measures of all staff, including internal investment staff. Include portfolio ESG performance alongside financial performance goals in assessment of outside portfolio managers. And measure all performance, including that of the foundation itself, through third parties and standard, peer-comparable metrics.

- Use external muscle for mission. Foundation “capital” includes social capital along with financial. Networks of insiders, collaboration at the investment management level and similar can accelerate impact rather than deflate it.

- Stop lending your goodwill to provide cover for bad actors. We all wish that big companies would help improve things. Make sure their core businesses—not just their corporate responsibility programs—are effective in making this real. Otherwise, don’t invest in them and don’t help them by, for example, “de-risking” their loans.

Making the Paradigm Shift

If leaders of large institutions—from banks to companies to foundations and nonprofits—are sincere in their desire to either prevent or solve wicked problems ranging from global heating to wealth inequality and institutional racism, the field must change its paradigm, operating model, and the societal norms it supports.

In foundations in particular, the underlying structure, beliefs, and ways of working—or paradigm—is unfit for purpose, and it has made today’s large charitable institutions complicit in enabling rather than addressing these problems. Foundations must reset their paradigm, and with it, their ingrained model, culture, and operating rules. Only then will they merit a public license to operate and the multitude of public subsidies they enjoy.

Notes

- A relatively small group of US private foundations have gone “all in” for mission, aligning their portfolios with their social aims, despite Heron’s early demonstration of its feasibility. By December 2016, Heron had shifted 100 percent of assets to mission. See Charles Ewald, Heidi Patel, and Jaclyn Foroughi, The F.B. Heron Foundation: 100 Percent for Mission – And Beyond, Stanford, CA: Stanford Business, 2018, accessed June 19, 2021.

- The financial data contained herein both of salaries and foundation assets is based on author’s compilation of information from GuideStar published tax filings based on foundation fiscal-year 2018 data.