October 14, 2015; Fox News

As NPQ reported a few weeks ago, California Governor Jerry Brown signed legislation that allowed physicians to assist terminally ill people by administering lethal doses of drugs to hasten their deaths. California is now the fifth state to legalize the right to die. (The first was Oregon, where right-to-die legislation was established 1997.)

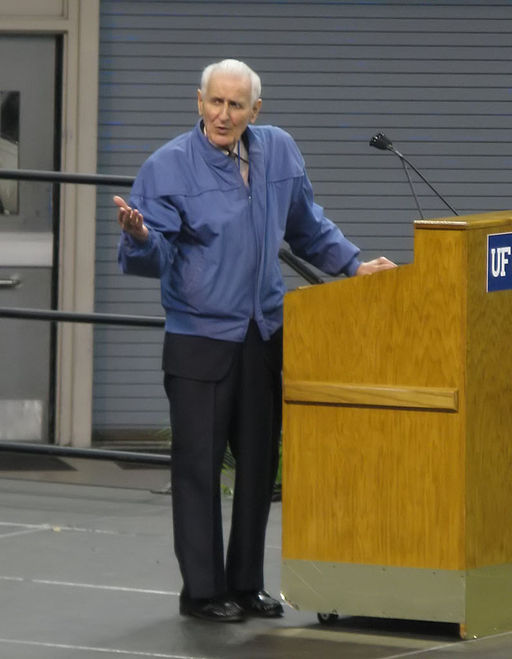

Ironically, this event comes at the same time that the University of Michigan’s Bentley Library announced the acquisition of a collection of papers and other materials from Dr. Jack Kevorkian, or “Doctor Death,” as the media dubbed him. In the 1990s, Kevorkian, a radical spokesperson for physician-assisted suicide (which he called “medicide”) sensationalized the issue. However, the collection will show another side of Kevorkian—a child of Armenian immigrants, a musician, and an alumnus of the University of Michigan Medical School.

The collection, donated by Kevorkian’s niece Ava Janus, includes papers and other material from Dr. Kevorkian, including video and audio recordings of his consultations with assisted suicide patients as well as historical documents from the Kevorkian family. The university said in a news release that the video recordings from patient consultations, often with family members present, consist of conversations about the history of their illnesses, the current quality of their lives, and their reasons for wanting to end them.

“Many of Kevorkian’s ‘medicide’ patients and their families—who remain very close to this day—are still advocates of their family member’s choice to die, so anonymity was not an issue,” said Olga Virakhovskaya, Bentley’s lead archivist who processed the materials. “We felt very strongly that by not providing access to this collection and to the medicide files, we would be choosing to hide a very important story.”

Virakhovskaya goes on to say that the lesser-known material about Kevorkian’s personal pursuits and family history is intriguing. “He was a brilliant student who graduated high school early. He spoke several languages and he was very artistically gifted,” she said. “Much of his ‘dark’ artwork that focuses on the subject of death can be found in these archives, along with recordings of his musical compositions.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This very personal look may give others a new understanding of Kevorkian and the corresponding issue of physician-assisted suicide. The hope is that a more personal look into Kevorkian’s life could lighten the dark persona of “Dr. Death,” who has become somewhat of a caricature in the intervening years.

“The release of his papers will allow scholars and students to understand the context of and driving forces in an interesting and provocative life,” said the Bentley’s director, Terrence McDonald.

Indeed, the collection shows what many modern assisted suicide activists already know: he was a pioneer in medical ethics. The university said that in 1952, as a graduate of the University of Michigan’s medical school, Kevorkian earned a reputation as a radical when he advocated for prisoners condemned to death to be given the option of euthanasia so that their bodies could be used for medical experimentation, as well as for harvesting healthy organs. It marked the beginning of his life-long advocacy for “medicide.” His defiance of established laws and protocol became a catalyst for opening up a vociferous national debate about what constitutes personal freedom in medical treatment and in end-of-life decisions.

Kevorkian acknowledged his first assisted suicide in 1990, after which authorities tried to stop him. The reverse effect happened, and the number of cases soared. He was charged four times with murder, but was acquitted of three with the fourth ending in a mistrial. In 1998, Kevorkian was found guilty of second-degree murder of Thomas Youk, who had Lou Gehrig’s disease. He served eight years in prison, and he died four years after his release.

Today, some consider Kevorkian the “godfather” of the Right-to-Die Movement. No doubt his bombastic style sensationalized the issue. However, nonprofit organizations like Compassion and Choices have been working for decades to advocate for end-of-life choice and to educate people about options that give them more control and comfort at the end of his life. Assisted Suicide fights for the rights of competent adults who are terminally or hopelessly physically ill. The Hemlock Society, which assists people in committing suicide, was already ten years old when Kevorkian first came onto the scene.

Many such groups have been on the forefront of helping enact tangible change, not only in the mindset of society, but also on the legislative level, as in the End of Life Option Act in California. The issue of assisted suicide remains as contentious as ever, and it’s uncertain whether a window into Kevorkian’s life will help alleviate the current tensions surrounding assisted suicide. But, just as importantly, it will certainly keep the issue a topic of heated conversation.—G. Meredith Betz and Shafaq Hasan