July 29, 2020; New Yorker and the Washington Post

This past spring, as the COVID-19 pandemic took off, the United States Postal Service (USPS) took an unexpected center-stage role as both an answer to the difficulties of protecting polling workers and voters from contracting the novel coronavirus—and as a political pawn.

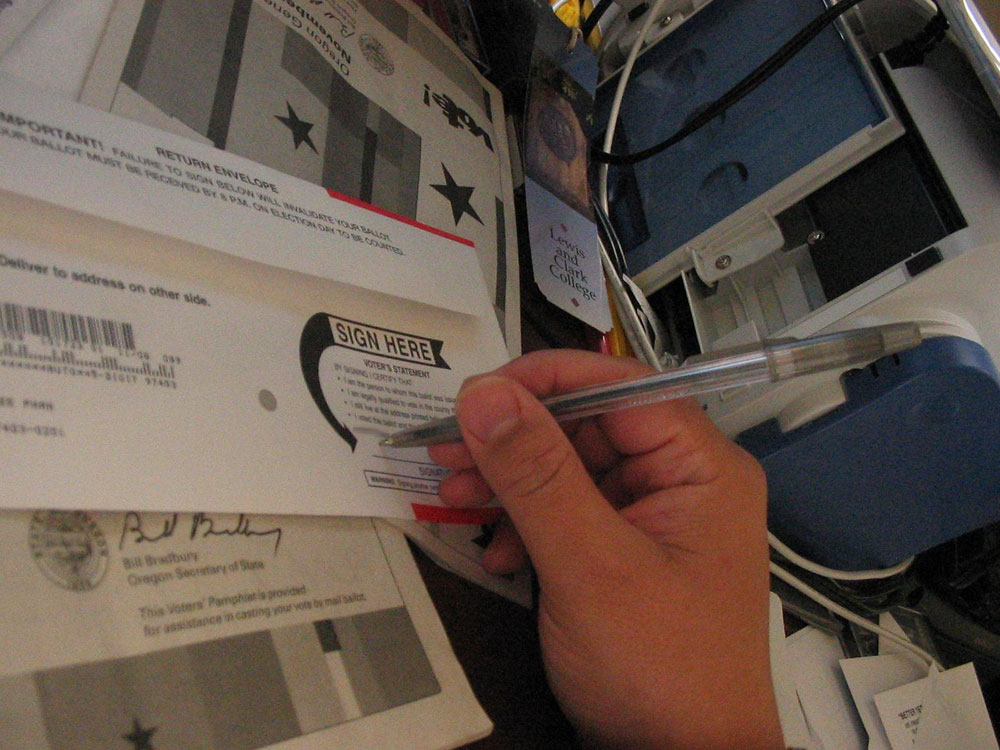

There are more than 8,000 counties and towns that administer voting in the US, placing the election system in very local hands with a variety of methods and guidelines. This patchwork system has contributed to systematic racist voter suppression in various ways over the decades, and this year, COVID-19 adds fear to the mix. When primary season came in the spring, use of absentee voting ballots skyrocketed. In April, Wisconsin’s primary saw a million people vote by mail, five times the 2016 level.

The Postal Service has been under financial stress due to a 2006 law that mandates that the agency fully fund its post-retirement health cost 75 years into the future to the tune of $72 billion—a requirement no other business has. Nevertheless, financial challenges and all, the Post Office remains an essential service.

A study by Microsoft found half the country does not have broadband or adequate internet access, and with many families house-bound by the pandemic, some individuals cannot pay their bills—or even receive them—online. Many other Americans, especially seniors, also prefer “snail mail” for bills and other communications. For many, the Postal Service remains a lifeline—sometimes literally, such as for those who receive medications by mail.

“The Postal Service has never been more important in modern times than it is today,” Devin Leonard, the author of Neither Snow nor Rain, a lively history of the institution, tells Steve Coll of the New Yorker. “You can’t have stay-at-home orders and not have efficient and equal home delivery…you need a governmental postal service to do that.”

To address financial shortfalls, however, the Postal Service has slowed its service. It started with standards that let first-class mail take up to five days to be delivered, a measure taken during the Obama administration. Now, mail that’s not ready at each day’s deadline for delivery waits until the next day to avoid overtime expenses. Bins of mail that could be delivered just sit there. If the hand-sorted mail is misdirected and the carrier brings it back, it can take an extra three or four days for the mail to arrive. Delays now mean no time to catch up, as the mail-heavy voting season and holiday season are just a few months away.

In addition, the majority of states will not accept ballots that don’t arrive by Election Day. Georgia disallowed more than 7,000 of the mailed ballots (three percent) in 2018. Some states further complicate the issue with ridiculously short timelines. Michigan and Georgia only allow four days to mail out the requested ballot and get it back.

“Mail delays meant that voters who did everything they were supposed to do” were nonetheless disenfranchised, Wendy Weiser, who directs the democracy program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, tells Coll. “We saw a lot of ballots that were rejected that shouldn’t have been rejected, cast by eligible voters, because of [deadlines] that don’t make sense during the pandemic.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Now more than ever, under a pandemic, the states have to find a way to work with the Postal Service. The 75th Postmaster General, Louis DeJoy, has only been on board since May. He is a businessman, and a longtime donor to President Trump and the Republican Party, having given $2 million in the last four years. He was approved unanimously. Immediately, he mandated changes, including those drastic cuts in overtime. DeJoy’s relationship to Trump puts his decisions and goals into question; the president has been vocal about his contempt for the USPS and mailed-in ballots, falsely claiming they’re a major fraud risk.

Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-NY), whose primary outcome in July was delayed for more than a month, sent a letter to DeJoy on July 20th, saying, “Increases in mail delivery timing would impair the ability of ballots to be received and counted in a timely manner—an unacceptable outcome for a free and fair election.” In a separate letter to DeJoy ten days later, four Senate Democrats demanded information about the new “questionable” procedures delaying the mail:

Your failure to provide Congress with relevant information about these recent changes or to clarify to postal employees what changes you have directed as Postmaster General, undermines public trust and only increases concerns that service compromises will grow in advance of the election and peak mail volumes in November.

DeJoy has implemented such a hard timeline that the mail sorting machines are shut down early in some regions to save money, meaning there is mail for carriers to hand sort, and then leave to make deliveries whether or not they are done sorting. It is purported that workers call the new Postmaster General “Louie DeLay.”

“The question of the day,” asks Wendy Fields, the executive director of the Democracy Initiative, a coalition of groups that advocates for voting rights, “is, will the leadership of the Post Office—the Postmaster General—understand that this is not just about vote-by-mail but about the whole infrastructure of our voting system? Is the Postmaster General going to do it proactively and be open to having a historic election that really embraces every single voter, or are we going to have more chaos?”

David Partenheimer, spokesperson for the USPS, says these changes are meant to fiscally stabilize the agency, not to delay the delivery of ballots.

“Of course, we acknowledge that temporary service impacts can occur,” he says, “but any such impacts will be monitored and temporary.”

Voters have noticed that mail is taking longer and the problems this creates, such as cutting by a week the time allowed to pay bills. All eyes are on the Postal Service. Can the Post Office perform in this year’s election? What’s more, can they prove Kris Kringle is real?—Marian Conway