Memphis, according to the 2020 census, is home to about 633,000 people, of whom 64.5 percent are African American. As a new report from the Black Clergy Collaborative of Memphis (BCCM) and Hope Policy Institute—the policy arm of Hope Credit Union, a Delta-based community development financial institution (CDFI)—demonstrates, Memphis is also home to an astonishing 114 storefronts of predatory lenders. That is more than one storefront for every 6,000 people.

Those 114 storefronts, the report’s authors emphasize, works out to “more than twice the number of Starbucks and McDonalds combined” citywide (2). This is just one finding in the two organizations’ new report, titled High-Cost Debt Traps Widen Racial Wealth Gap in Memphis, which examines at the micro level how daily extraction of wealth from Black Americans occurs in the city of Memphis, Tennessee.

Memphis, as census data also show, is tied for being the nation’s second poorest big city (500,000 or more people), with a 2020 poverty rate of 24.6 percent. By stripping assets out of low-income and especially Black neighborhoods, predatory interest-rates reinforce this poverty. In Memphis, 45 percent of Black households and over 50 percent of Latinx households are unbanked or underbanked, compared to 15 percent of white households (6). People who lack full bank services, of course, are the people most likely to turn to alternative sources of finance, including predatory lenders.

Memphis in Context: The National Reach of Predatory Lending

At NPQ we have written regularly about the racial wealth gap. Often, the focus is on how to build BIPOC wealth. But no one should lose sight of the fact that BIPOC wealth is stripped from communities every day. As Jeremie Greer of Liberation in a Generation wrote in Shelterforce earlier this year: “The racial wealth gap is a systemic problem, not a product of Black people’s personal choices. And no matter how many wealth-building opportunities we create for Black people and other people of color, these efforts will never deliver if we leave the wealth-stripping processes intact.”

One of the processes that Greer describes is predatory lending—loans with triple-digit interest rates. According to an article published by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “payday lending” is a $9 billion market. As economist Jeannette Bennett writes, on average “the typical $375 loan will incur $520 in fees because of repeat borrowing.” If one adds check cashers and related enterprises, the size of the predatory lending industry is even larger. One estimate puts the number at $19.1 billion. Black and Latinx families are disproportionately affected. And as a recent study by Jim Hawkins, a University of Houston law professor, and Tiffany Penner, a recent law school graduate, published in the Emory Law Journal documents, marketing is skewed to attract borrowers of color.

In their article, Hawkins and Penner found that in Houston, “while African Americans make up only 15.6 percent of auto title lending customers and 23 percent of payday lending customers, 34.8 percent of the photographs on these lenders’ websites depict African Americans.” They add that 77.3 percent of the advertisements at physical locations that they surveyed targeted borrowers of color.

How Predatory Lending Extracts Wealth from Communities

Predatory lenders go by many names: payday loans, car title loans, and flex loans being the most common. Regardless of the name, what they share are triple-digit interest rates and coercive repayment mechanisms. In their report, Hope Policy Institute and BCCM outline how these lending mechanisms work:

Payday loans: In Memphis, under Tennessee state law, a borrower can charge an annual percentage rate (APR) of 460 percent on a two-week loan. Some states permit even higher interest rates; Texas has highest in the country, with a 664 percent APR.

What does 460 percent translate to at a biweekly pace? Effectively, this works out to a fee of slightly more than $17.50 per $100 borrowed. As the report’s authors explain, “Payday lenders take access to a borrower’s bank account either through requiring a post-dated paper check or electronic bank authorization (ACH) as part of the loan transaction. This means that on the day a borrower receives their income – whether it be their paycheck, stimulus check, or Social Security check – the payday lender stands first in line for repayment” (8). These loans can—and of course regularly are—rolled over for a price; over 75 percent of payday lender fees are generated by people who borrow for 10 consecutive two-week periods or longer.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Car title loans: These are secured not by a paycheck, but by a vehicle. According to the report’s authors, a typical $300 loan will carry $66 in fees for 30 days, an effective APR of 267 percent. Like payday loans, these loans are typically rolled over—according to national data, on average eight times. In Tennessee, in 2019, the most recent year for which data is available, 45 percent of car title loans issued that year went into default, and over 11,000 cars were repossessed (9). Notably, 2019 was, relatively speaking, a good year for car title borrowers in Tennessee. Over the six-year period from 2014 through 2019, title loan companies repossessed over 101,000 cars statewide—an average of nearly 17,000 repossessions per year.

Flex loans: These were created in Tennessee in 2014 and act as an open-ended line of credit that can be secured either by a paycheck or car. While payday-loan borrowing is capped at $500, , flex loans allow you to borrow as much as $4,000.  Tennessee State law sets the interest rate for flex loans at 24 percent; however, borrowers must also pay a daily carrying fee, or “customary fee,” of up to 255 percent, resulting in an effective combined 279 percent annual rate (9).

The Geography of Lending

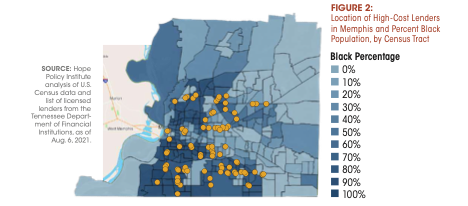

As noted above, marketing efforts by predatory lenders focus on attracting borrowers of color. Additionally, when you look at a map of Memphis’ 114 predatory lending storefronts, it is clear that the location of those storefronts is anything but random, with nearly all located in neighborhoods heavily populated by people of color.

In addition to tracing the geography of the storefronts’ physical location, the report’s authors also trace the geography of the storefronts’ ownership. As the report details, 74 of the 114 storefronts are owned by firms headquartered outside of Tennessee, with 52 of them owned by just two firms—Ace Cash Express (Populus Finance Group) of Texas and Title Max (TMX Financing) of Georgia. This means that over half of the profits generated by payday lenders, title companies, and flex lenders are extracted from the Memphis community entirely and end up instead in the hands of out-of-state investors and managers.

Policy Solutions

There are many complicated issues regarding economic policy. However, ending triple-digit interest rates is not one of them. As BCCM president Reverend J. Lawrence Turner says in the report, which he coauthored, the impact of charging up to 460-percent interest on loans serves to “effectively ensnare the working poor into webs of long-term debt” (7).

It’s worth noting that today’s predatory lending is a relatively recent development. As Pew Charitable Trusts has documented, while it may seem that payday lenders have always been with us, that’s not the case. Starting in 1916, and continuing for many decades, states limited monthly interest rates at 3.5 percent; annual APR ratings varied throughout the states from 18 to 42 percent. This changed with deregulation of consumer protections in the 1970s and 1980s. As Pew puts it, “As this deregulation proceeded, some state legislatures sought to act in kind for state-based lenders by authorizing deferred presentment transactions (loans made against a post-dated check) and triple-digit APRs. These developments set the stage for state-licensed payday lending stores to flourish.”

Even today, just 18 states and the District of Columbia cap loans at annual rates of 36 percent or less. They include many states in the Northeast (Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Maryland). But many others have also acted. For example, in the South, Arkansas, West Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia have passed similar laws. In the West and Midwest, similar laws exist in Illinois, Montana, South Dakota, Nebraska, Colorado, and Arizona. A recent American Banker article adds that similar legislation is currently being debated in four more states—Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, and Rhode Island. There is also pending federal legislation introduced by Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) that would create a 36-percent maximum rate nationwide.

The report’s authors add that even if the Senate blocks legislative action, the federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau could use its regulatory authority to act. “The CFPB,” the authors insist, “has the ability to issue new rules that ensure high-cost lenders, such as those in Memphis, do not endlessly trap people in unaffordable cycles of debt as they do now” (7).