Credit: Amy Costello

Amy Costello: Welcome to Tiny Spark, a podcast of the Nonprofit Quarterly. We focus on what is required to build a more just society—in matters of race, health, the environment, and the economy. I’m Amy Costello. Today, we’re talking about how to ensure housing for all. The Department of Housing and Urban Development has reported that in the United States last year, nearly 600,000 people experienced homelessness on a single night. So, we’re going to spend time with a nonprofit that has a theory about why so many are without a place to live and what to do about that.

Let’s take a spin.

I’m in my hometown of Austin, Texas, riding in a golf cart with Alan Graham. He’s CEO and founder of Mobile Loaves & Fishes and he’s giving me a tour of this 51-acre master-planned community. It’s called Community First!

Alan Graham: So, a lot of people come out here, this is a 3D printed house right here. And you know, a lot of people come out here and they, they wanna, we wanna see the 3D printed house. We want to see the cute tiny homes.

Costello: We’re passing dozens of well-kept tiny homes, dressed up in perky colors: tangerine and turquoise, sunshine yellow. And even the names of the windy streets we drive down are pleasant, too. There’s Mi Casa Drive. Just off of Goodness Way, you can take a right onto Grace and Mercy Trail. Many residents have grown gardens in front of their homes. There’s a park and plenty of green grass around here. In addition to the tiny homes, some residents are living in large RVs that are lined up neatly along the side of the road.

This place is home—quite literally—to more than two hundred men and women. All of them have previously experienced homelessness for years and years. Alan Graham has a theory about why so many people in cities across the nation are living on the streets and in shelters.

Graham: The single greatest cause to homelessness is a profound, catastrophic loss of family. And it kind of turns out that this is the one thing that people don’t necessarily want to hear.

Costello: Why do you say that?

Graham: Because I think it opens up complexities in our culture, because if you go upstream to where all this is happening, it—to us—is the fundamental breakdown of the family, and we’re not talking the nuclear family of a mommy and daddy and all that—that’s a component of that—but the breakdown of community. And then our other foundational belief is that housing alone will never solve homelessness, but community will. Because it’s imperative that you and I be in relationship because I know—and you and I have never met—that there are two things about you that are a guarantee. You desire as a human person to be fully and wholly loved, and you desire as a human person to be fully and wholly known.

Costello: And if you’re struggling with addiction say, as around half of those experiencing homelessness in America are, you might not want to be fully known by anyone, certainly not by family, not by neighbors, and unless you’re fortunate enough to have a really solid safety net, you may very well go off and isolate yourself from anyone who loves you or knows you.

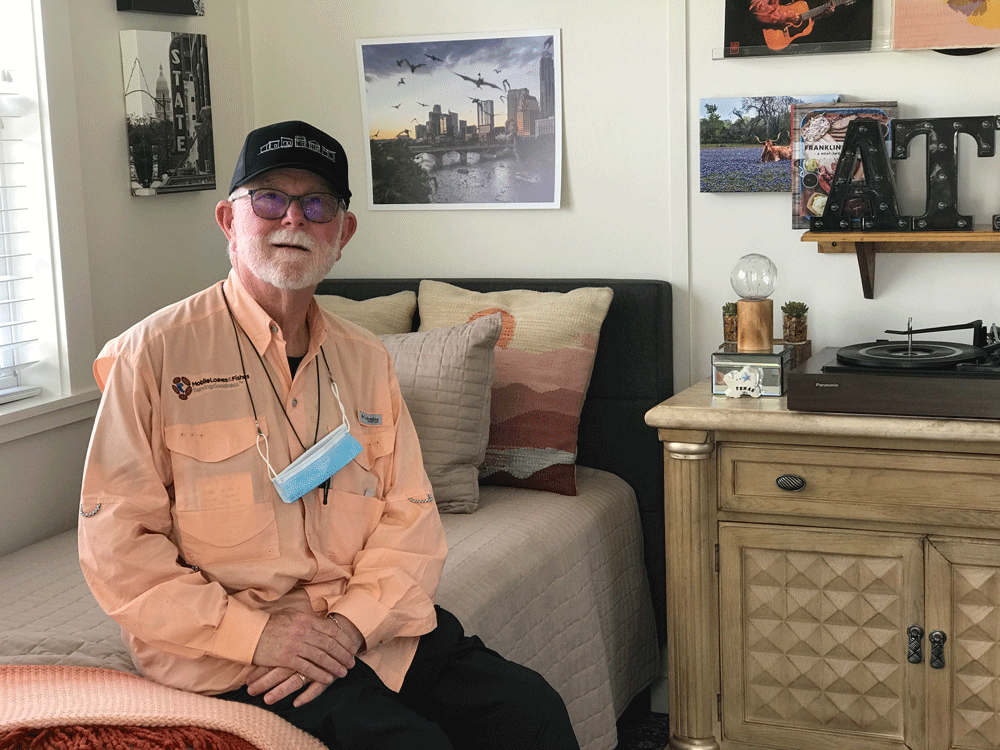

Tim Shea has been living at Community First! for six years. He’s got a ginger-colored beard that’s turned mostly white now. And he has laugh lines around eyes that have seen a lot of hardship over the course of his lifetime. Tim says back when he was using, he didn’t want anyone to miss him or feel concerned about him.

Tim Shea: As I would get more strung out, I would push people away, ‘don’t come by.’ And I would do things to hurt their feelings. ‘Yeah. Good. You’re mad. I’m glad.’ You know, that type of thing.

Costello: So, I don’t have to deal with you.

Shea: Yeah, I don’t have to deal with you. I don’t have to deal with the shame that I know that, or the, not shame. I felt shame, but they just felt disappointment. And you get tired of disappointing people, you know, and when I would move, you see, back in the 50s, 60s, 70s, you can move and like, just assume another character. It’s pretty easy, you know, and I’ve done it. I’ve moved all over the country. And you start all over and everyone you meet thinks you’re, you’re a cool, dude, you know, you’re that. And then when I relapse, like, I can’t even face them, you know, they don’t even know what I’m doing, but I know what I’m doing. And so, I start destroying the relationship. And that’s, I think, pretty typical of addicts. You know, he’s just a miserable S.O.B. You know, he’s, he really probably cares more than you think, you know, it’s just that caring is what makes them want to push you away from, you know, especially the real close relationships, you know like kids and wives and whatever.

Costello: Kids and wives, Tim has had both during his lifetime, but he lost them during his many decades-long battle with addiction. Today, when you look at Tim, his eyes are clear and a deep shade of blue. And he says he’s in a better place now, because he knows there’s a difference between simply being clean, and actually enjoying life.

Shea: I’ve been clean for a long time, but just not using isn’t as fulfilling as when you are surrounded by a community of people that are encouraging and nurturing and stuff. So, that’s what I’ve gotten here.

Costello: We’re sitting on the back deck of Tim’s neatly kept home. And just over a low wall, you can see another tiny home, where his neighbor lives.

Christina Hite: I’m Christina Hite and I am one of the missional neighbors here at Community First!

Costello: And what does it mean to be a missional neighbor?

Hite: So, in our village, we have about 80 percent of people who have been chronically homeless. And so, then our missional neighbors are those of us who feel called here by God to live intentionally here, and just to come alongside our neighbors in whatever way that looks like, a lot of friendship-building, relationship-making, just being present to be diverse and present to people.

Costello: And what does intentional living mean to you?

Hite: Well, for our family, so my husband and my two girls live here, they’re nine and eleven, and for us, it looks like just being around the village as much as possible. We love being outside. We spend a lot of time on our porch, get to know our very closest, nearby neighbors a lot because everybody’s porch faces inward. And so, kind of just being around a lot helps people build trust. And then, kind of from there you get to hear people’s stories, get to understand some of their needs, some of their unique background, and then you know, help them connect to resources, whatever they need. So intentional neighboring looks different every single day.

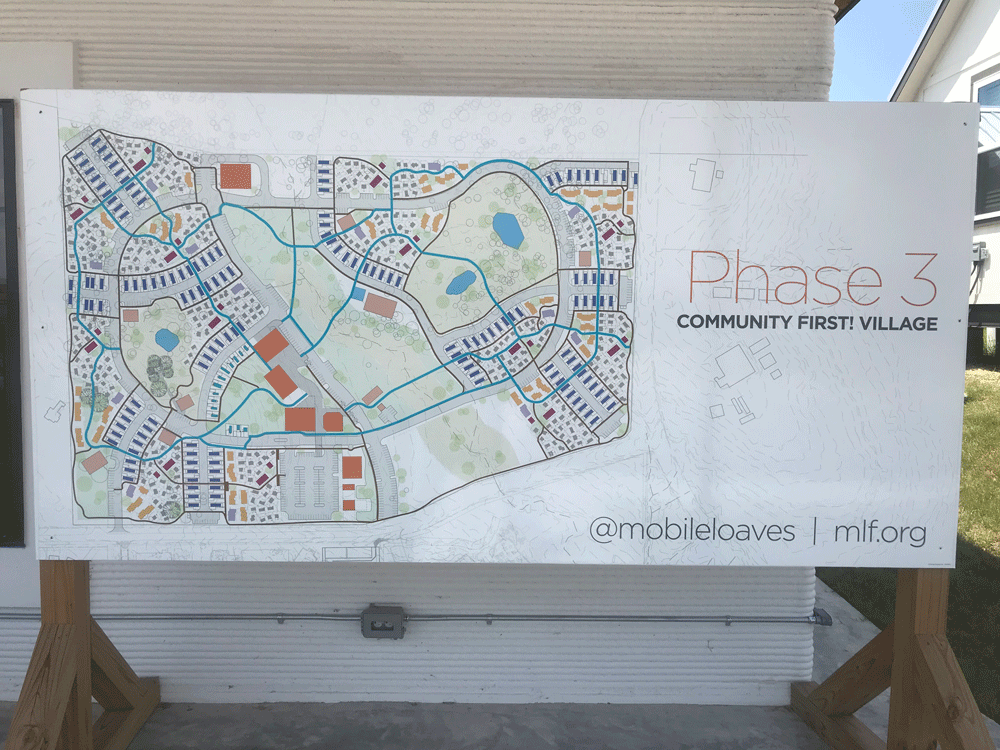

Costello: Founder and CEO Alan Graham says missional neighbors like Christine and her family, who make up about 20 percent of the residents here, are key to the success of Community First!, which continues to expand since the village opened in 2015. They’re currently in Phase Two of development and they’re adding 310 more homes to this community. And soon they will unveil the next phases which will comprise another 1400 homes.

Alan says other nonprofits around the nation regularly take part in Mobile, Loaves and Fishes’ training sessions which help organizations adapt the Community First! model to their own cities.

As he was showing me around, I could tell Alan just wants more people to live this way. In fact, he and his wife live here themselves, in their own tiny home.

Graham: This is literally the best neighborhood I’ve ever lived in. The most diverse neighborhood I’ve ever lived in. And it just, a day doesn’t go by that doesn’t provide entertainment. Some of it, you know, the human struggles of people that are battling addictions and mental health issues. Love this place.

Costello: This community is located outside of downtown Austin, about eight miles from the State Capitol. Google maps shows that it would take anywhere from an hour to an hour and a half to get here by public transportation. And this is one of the challenges in cities across the United States: finding large tracts of land—near enough to city centers—on which to build new homes for people who’ve spent years living on the streets. And even converting existing structures into ones that could provide affordable housing is also a huge challenge.

Alan says there’s one reason why in cities and suburbs across the nation, we haven’t built more homes like the ones Alan has built here: NIMBY.

Graham: Not in my backyard. Never, ever in my backyard. And until we overcome that singular impediment. Period. We’re going to be stuck in this calamity forever. This is an issue of human beings saying yes in my backyard.

Costello: Here at Community First!, families who’ve never experienced homelessness have said an emphatic ‘yes in my backyard.’ And as we sat on Tim’s porch, I wondered how these neighbors—who in another world, might never have met—get along day to day.

I want to talk about the missional families. And of course, we have Christine’s house right here, next door to yours. How important are the missional families to you and your experience here, if at all? Are they important or and…?

Shea: They are essential to me.

Costello: Why?

Shea: Well one is, it’s just amazing how people can be so willing to give of their time and their effort and everything, their emotions for other people. It just blows my mind, you know, because addiction is a very selfish thing and you’re not going to make it in that world if you’re not, you know, just totally focused on yourself all the time, getting high and fighting, whatever. And these people have come here and they’re successful people, have great lives and choose to live with us. I mean, that is just, you know, I can’t get people I know who love me, want to live with me, you know?

Costello: So, this is what founder Alan Graham is building here, or rather rebuilding for residents. The thing he says is the single biggest cause of homelessness: a loss of community.

And you can hear the way that Tim is finally getting to experience a taste of what it’s like to live in community. He says as a kid he was left on his own a lot. But now, when he turned 71 recently, he got to experience the sweet taste of community-living with his neighbors, the Hites.

Shea: Because we sort of have developed a relationship, their kids—my birthday cards—they made for me. And that’s the way the Hites are. You know, the kids aren’t gonna, they won’t go buy a birthday card. They make a card, you know, and they’re sitting on my refrigerator.

Costello: What homelessness expert can measure the meaning or transformational impact of a handmade birthday card, drawn by children and given to a man who hasn’t often experienced a sense of community in his life? And what does that simple act of love do to a man like Tim, who has so often just pushed away those kind of relationships when he was deep in his addiction?

Could it be that intangible things like a sense of family, community, love, even, are in fact, necessary ingredients to keep more people in permanent housing?

Alan Graham is betting on these small gestures, these tiny interactions, and deeper relationship-building will keep people like Tim in his house, and off the streets forever. When people move here, they’re given a home permanently. And it’s older folks who tend to live here. The average age of residents is 58.

And while most of them live in tiny homes, Tim’s is one of the few here that was made with a 3D printer. He takes me inside. The walls are textured in puffy white strips. It’s kind of serene, like you’re surrounded by marshmallows or something. There’s a rickety ceiling fan turning. And I asked Tim to describe his home to someone who couldn’t see it. And without missing a beat, he replied, ‘Encapsulating.’

Shea: You feel encircled here, the way it’s set up. There’s no sharp corners, no edges. It’s all circular and the high ceilings, the big windows, what do I got? One, two, three, four, five windows in the living room. Pretty cool, huh? Very airy. And with the white Lava Crete walls. And I didn’t think I thought maybe it would be dirty or, you know, get dirty really easy. It doesn’t seem to be happening and I’ve been in here a year, and it looks great! It’s easy to clean. The counters are all slate, real nice. Everything just seems to, I don’t know. It’s wonderful and I love…Sometimes I just sit in here and I just look, you know, just, just taking it in. It’s just a great place to live in. I feel comforted. I feel safe. And, I don’t know, just sort of makes me wish I had found it, I got here a lot earlier. You know, I had a good 20 years in here, but…

Costello: Maybe you wouldn’t have been ready, though.

Shea: Yeah, maybe I wouldn’t have been ready, yeah. You just never know about something like that. And, and I wouldn’t want to take a space for someone who really was at that place. So, it worked out for me. It was just the right time at the right place.

Costello: There are plenty of men and women in Austin who would like a place like Tim’s. Alan says there’s about 170 people on the waiting list, and about ten new residents are welcomed every month. And the neat houses that residents live in are hand designed. Before residents arrive, they’ll be asked about their tastes. What do they love? Maybe it’s pro sports or country music. And then staff here go and find pictures and objects that reflect those passions of the incoming resident, so that when they arrive here, they walk into a home that, well, feels like home. So much of what goes on here is aimed at making residents feel a sense of pride again after years and years of just barely getting by in life and being disparaged by so many segments of society.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Residents—or neighbors, as they are known—must pay rent here. In fact, the number one rule in the Community First! village is that rent, which ranges from $225 to $500 a month, must be paid on time. And you can’t move in until you can show a sustainable payment plan. Like Tim, some use disability payments and social security, or as Alan explains, others might be able to get a job with the so-called Community Works program right here in the neighborhood.

Graham: We are currently on pace right now to probably see our neighbors earn around a million one, to a million two, this year in what we call dignified income. People want to work. That’s the bottom line. So, if you see the panhandler on the street corner and you want to call that lazy, come spend an hour with me panhandling and you’ll realize what a miserable life that is. They would prefer to sell you bottles of water. We just don’t let them do it.

Costello: So, you’re saying in the past year or so, you’ve paid out about a million to people who live here through the work that they’ve done?

Graham: That’s correct.

Costello: Do the residents have any say in terms of like how this organization operates, do you have them on, I don’t know, let’s say the board or do you have, do they have input on the decisions about how, what goes on in the community or what is their role in that regard?

Graham: There’s a community council that gathers once or twice a month. It’s an elected group of people. I think we kind of lost that during the Covid deal because of all the gathering stuff, but that will make its way back and there will be input that will be taken into consideration. But they’re not on the board. They’re not, you know, necessarily making decisions or giving advice and counsel, and many times that advice and counsel is listened to. But you know, we, we run, we run this deal.

Costello: Has there been any discussion about bringing some residents onto the board?

Graham: To be on a board of this magnitude is very complicated, and we’re dealing with men and women that come from extraordinarily traumatic backgrounds. So, the average age here is 58 years old. The average number of years on the streets is ten years. Sixty five percent of our neighbors have two or more comorbid diseases. The average age of death is under 60 years old. There are tremendous addiction issues. There are tremendous mental health issues here, and it would not be an environment that would be conducive for them. But I have spent my life with these men and women. I have spent over 250 nights on the streets sleeping with them. I live in the middle of the community. Many of us do. And I value who they are and their advice and counsel. And this community was built upon those relationships that we have. So just gratuitously adding them to some thing would be difficult. Mostly, what our board needs to do is raise millions and millions of dollars in order to keep this machine moving forward and getting more people up off the streets.

Costello: What is your annual budget?

Graham: The annual operating budget would be currently probably $8.2, $8.3 million. Capital budget’s going to be extraordinary. We’re probably going to be approaching twice that amount. So it’s a lot of money, and we’re about to move into a campaign that will ultimately need to raise about $150 million. So, we need those relationships of people that can come in and leverage their halo to help us do that.

Costello: And I don’t want to touch on this too long, but my understanding is, and I might be misinformed, which is entirely possible. I think that in a lot of like, homeless shelters for instance, or other places that might be a spot for people without homes, there are very strict policies about it, I think. You know, no drinking, no drugs, very punitive in that sense. And you could have, I imagine, made that rule here too, right? If you’re going to live here, there is no drinking or there is no drug use, and just, you’ve talked about it a little bit, but why didn’t you go that route?

Graham: Well, there would be no one living here if I went that route.

Costello: Christina Hite and her husband Dustin were working as pastors at a church in Peoria, Illinois when they visited Community First! Christina says it took her about two and a half hours to fall in love with the place. When I spoke to her, they’d been living here for about six months, and she told me that in that time, they’ve learned so much from their neighbors.

Hite: I mean I already knew this a little bit but there’s such generosity. It’s overwhelming sometimes, first of all, because we don’t have space to put things. So, I don’t, we don’t need any more toys. But second, because it’s people who you assume have had so very little, they want to give. They want to share what they do have. They want to bring you something that they’ve made, a treat that they’ve baked. They want to share, you know, flowers from their garden, cut you some fresh ones and bring them to the girls. It’s like generosity is almost what they lead with. And I think we all can learn so much from that instead of like, what’s mine is mine and I’m going to save it, I’m going to hoard it. It’s almost the opposite here. It’s like, I finally have things, and I definitely want to share them because I know what it was like to be without. It blows me away. Pretty much every week we’re like, Wow, I can’t believe how generous that was.

Costello: And do you think you’re a different person today than you were a year ago?

Hite: I’m sure I am. I think one of the big changes for us coming out here is that we were used to being leaders and being in charge of things. And what we’re doing here now is we’re just showing up as our regular everyday Dustin and Christina-selves. And there is a lightness and a freeness that comes with that, where you don’t necessarily, our missional team is amazing and we can get a lot done, but we also can just be. And there’s something about just being with people that is enough out here. You don’t have to find a task to do. You don’t have to organize another event. If you just come as yourself, that’s enough. And for somebody who has been in charge a lot growing up, and led all the clubs and all the organizations and then, you know, led, helped lead churches. It’s, I’m, I’m different because of that where it’s just I’m freer and lighter. And while some people might think, how is that possible, moving to a community like that, it completely is. It feels like a load off to just be present with people, and to have ministry look like that rather than organizing it all. And so…Hi, how’s it going?

Costello: And just like that, Christina’s wish to live intentionally in the community, comes to fruition when a neighbor pops by.

Neighbor: Honey, I’m sorry to bother you and I don’t have my mask, so I’m having an issue with getting to the market. I was just informed you were a missional.

Hite: Yeah, the one, the one right here on, on site?

Neighbor: I just need to get to the store.

Hite: Oh, to like JD’s?

Neighbor: Yeah, that would work.

Hite: OK. So, we’re, I am finishing up an interview, would I be able to come by your house in a little…

Neighbor: Yeah, I’m over here at 1300.

Hite: Oh, OK, yeah, that sounds good.

Neighbor: Sorry I bothered you.

Hite: No, you’re, no problem. Yup. Yeah, we’ll come back in a little bit. Uh-huh.

Costello: Tell me about what just happened there.

Hite: OK, so we had a neighbor who we talked to a few times. She’s actually brought gifts for our girls before, Barbies, and she just asked if she could get a ride to the grocery store. So, there is a bus system that comes out here, but you know, busses in big cities can take a long time. So, a lot of times people ask for rides to the closest grocery store. So, yeah, we’re happy to do that. So probably just do that in a little while. It’s nice to have a free schedule. There’s, one of the values out here is flexibility. So, there are times when we aren’t able to do that because we have stuff going on with our kids. But if we’re able to, then we just jump right in. It’s a pretty easy task.

Costello: And easy tasks to Christine can help a neighbor experience a level of security that was very hard to come by when living on the streets. For Tim, after six years as a resident of Community First!, he treasures the consistency that life here affords him.

<<

Shea: I don’t really ever have big ups and downs now. You know, it’s always just sort of level. You know, I know I’m bored sometimes, and that’s when I got my cat. I got my motorcycle. You know, you find other ways to fill those little holes in your life, you know?

Costello: And you say you, now you’ve got a lot to lose, right? Like, you know, and you’re aware of that. And when you look around here and you think about your life right now, like talk to me about some of the things you really cherish that kind of keep you grounded in this space, like what do you love about your life right now?

Shea: Belonging. I really feel very strong about the relationships that, I can’t say I developed. The people here, especially the missionals and staff and the residents. But the missionals and the staff reach out to us, to connect with us, to try to, you know, open us up a little bit because my, my main go-to is isolation. So just to get a house or an apartment, just shut the door, close all the blinds. And that’s when I get devious, you know. I can get high for a week. And then, you know, well if I don’t show up somewhere in a couple of days, someone’s going to come knocking on my door, not because they’re worried about me going back to drugs, but they just notice that I wasn’t there. And that’s a sense of belonging that, either I didn’t have, or I didn’t permit myself to have because I didn’t them want to know my secrets, you know? And now I can let people into my life. And that’s another very strong thing for sobriety is to know that you have let these people in, because all during the addiction, it’s pushing people away. Their disappointment, their whatever. So, even when you stay clean for a couple of weeks, you don’t want to tell anyone because you’re afraid if you go back and that’s another time you failed in your friendship, you know. So now it’s like, come, knock on the door, I’m wide open for anybody. And if you don’t see me in a couple of days, feel free to knock on my door and call me or whatever. And there’s a ton of people here that that will do that. And it’s not all me being the outlaw or me being this character, you know, because there’s, every one of us here is a character. Every one of us have, has a major story, and it’s not all popcorn and lollipops. And so, that’s why I think is such an important factor here is the missionals and the staff and how the mentality of just, you know, connecting with us and nurturing us and trying, just modeling a good lifestyle. And I love that.

Costello: And Alan Graham and the folks at Community First! hope even more people will get to find a better lifestyle with them. As the community, and indeed the United States moves forward from the Covid-19 pandemic, President Biden has launched the American Rescue Plan Act to deliver direct economic relief to those in need. In September 2021, Travis County Commissioners here voted to allocate $110 million to fund around 2000 affordable housing units in Austin. Nearly half of that will go to an initiative to house 700 residents through a collaboration that Community First! is involved in.

This article is a transcript of the Tiny Spark podcast.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

Community First! website

Nicole Foy, “Austin plan calls for spending $515 million on homelessness over three years,” Austin-American Statesman, October 25, 2021.

Usha Lee McFarling, “The uncounted: People who are homeless are invisible victims of Covid-19,” STAT, March 11, 2021

Chris O’Donnell “How we treat homeless people with mental illness and addiction must change,” The Irish Times, October 26, 2021.

Ben Thompson, “Austin’s Community First Village for the formerly homeless announces 127-acre, 1,400-home expansion,” Community Impact Newspaper, April 14, 2021.

Tiny Spark Podcast: “Should We Give Our Cash To The Homeless?,” December 22, 2017.