July 12, 2019; New York Times

Last month, the state of New York passed a strong climate change bill, the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act. The goal of the legislation is to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions by 2050—specifically, to reduce emissions to 85 percent below the levels in 1990. The city of New York passed climate change bills of its own in April that has the same zero-emission goal as the state. Hitting the ground running with that objective means reimagining one of the most iconic skylines in the world.

A 2017 report calls out the city’s buildings, mostly residential ones, as guilty of producing two-thirds of the greenhouse gases that are warming the planet. Accordingly, the NYC legislation has strict pollution rules for the approximately 50,000 buildings that are 25,000 square feet or more. It charges fees for noncompliance and offers loans to install renewable energy modernizations.

All the real estate—every piece of the housing market, old to new, affordable homes to penthouses worth multiple millions—is involved. Even older buildings will have to be brought into compliance. That skyline will come to include “green roofs” with plants and grasses, solar panels, or even wind turbines.

“I look out the window of my New York office, and I get a little panic attack,” said Lois B. Arena, a director at Steven Winter Associates, a design consultancy, about the scale of the new green mandates. “Oh, my God, all of those buildings?”

Those on opposite ends of the fiscal spectrum will probably having the easiest time adapting. Those who live in affordable housing will receive government incentives to enhance their real estate, and the wealthy can surely cover the costs of changes. The challenge will be for those in the middle of the income scale.

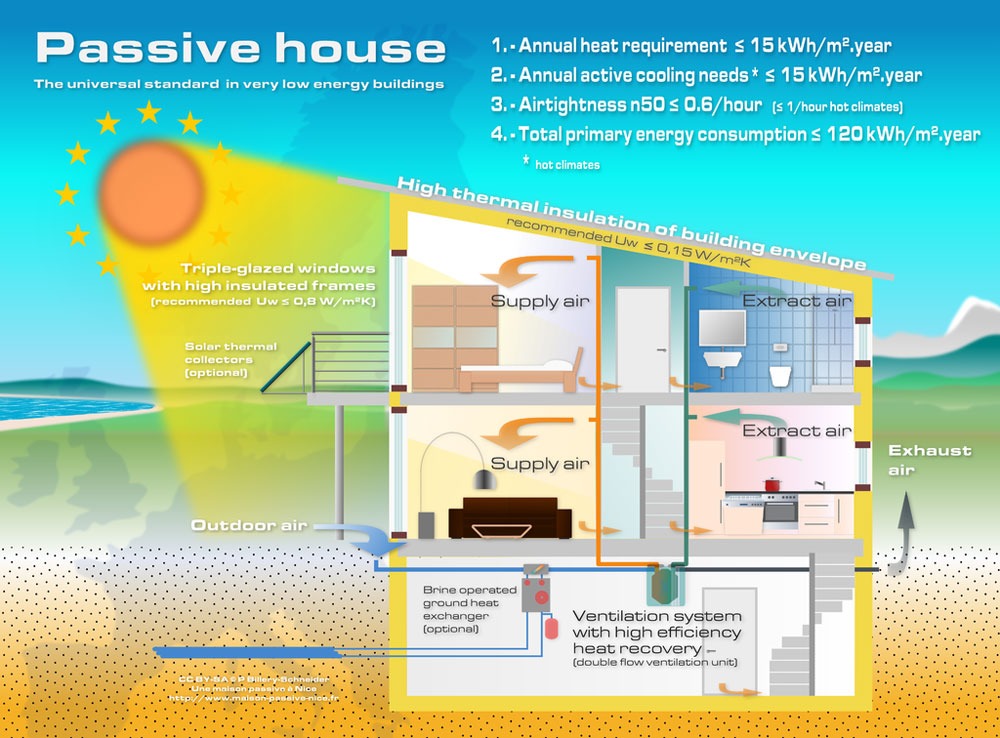

Andreas M. Benzing, architect and the president of New York Passive House, which promotes ultra-energy-efficient building standards, says 119 passive house buildings—again, mostly residential—are complete or becoming so. New York Passive House received its ruling as a 501c6 business league in 2014. Benzing says that interest in passive houses is growing, and the two- to five-percent upfront costs are recouped. Others say the changes needed to make a house passive-compliant can cost a builder 10 percent more.

Urban planner Jonathan Rose says “affordable housing has the largest penetration of greenness of any building sector.” Passive energy systems cost less to operate, which is a critical point for any developer building affordable housing. In Far Rockaway, Queens, government subsidies partially funded a new project on land that was severely damaged by Superstorm Sandy. The first floor is seven feet above the sidewalk, along with an elevated patio that can serve as a rescue boat dock, and the whole thing follows German passive house guidelines, with better insulation, less glass, and more opaque walls. About a third of the first 360 affordable units will go to the lowest income renters, families of three that make less than $29,000 a year, with some reserves for people who were formerly homeless. Another affordable apartment complex, 709 units being built in East Harlem, may be the largest passive house complex in the United States.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Luxury real estate is more problematic when it comes to cutting emissions. It takes more to heat or cool apartments with floor-to-ceiling windows, especially when the ceilings are overly high.

“It’s like saying a 12-cylinder Ferrari is more efficient than it was yesterday—they still use a lot of gas,” said Stephen V. DeSimone, the chief executive of DeSimone Consulting Engineers, who has worked on several supertall and high-end buildings. Luxury and sustainability, he said, are “sort of at odds with one another.”

The city rules will place annual penalties on those who have not cut their carbon emissions, with the aggregate first target of 40 percent by 2030. The city is hoping the penalties will be the deterrent needed.

While developers building new structures are working the requirements into their projects, the majority of the work to meet climate change goals must be done on existing buildings. The director of the mayor’s Office of Sustainability, Mark Chambers, estimates that retrofitting will cost landlords around $4 billion.

“Quite honestly, a lot of people are less focused on green energy and more focused on putting food in their mouths,” said Scott J. Alter, a founder of Standard Companies, which is renovating a 151-unit affordable rental building in Hell’s Kitchen. He commended the city’s goals, but is concerned that green updates, like new boilers and windows, can snowball into costlier projects because of the age of some buildings.

New York is behind cities like Los Angeles when it comes to solar installations, even with the country’s largest solar panel installation on a Manhattan apartment complex in Stuyvesant Town—Peter Cooper Village. The Bronx’s Co-Op City is next in line.

In June, New York reduced owners’ incentive to make capital improvements in their buildings with rent control reform. Rose says, “It will take them longer to do basic upgrades, much less transform them into climate responsive buildings.” Also, some will never be first to take the risk, and will wait to hear how much it costs to retrofit similar buildings and how much is really saved in energy costs.

Now, let’s see about improving that electrical grid.—Marian Conway