Editors’ note: This article, which comes from the fall 2008 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “Working Nonprofit Style,” discusses tools to improve organizational decision making. These tools can identify who should make critical decisions and how participants should make them. The authors explain these tools and offer a case study in how these methods helped diagnose a decision-making challenge, clarify zones of responsibility, and streamline decision making. Decision-making tools of the type discussed here have been in use from at least the 1970’s (an early approach to this can be seen in Vroom and Yetton’s 1973 piece entitled “Decision Making and the Leadership Process”). The tool discussed in this article, RAPID,1 is one of several models currently available to help organizations formalize and make conscious choices about how decisions are made.

How decisions are made can reveal a lot about how an organization performs. Consider some of these decision-making scenarios:

- Without consulting any of those who will actually do the work, an executive director promises an old friend that his organization will take on a complex project, leaving his staff feeling out of the loop and disgruntled.

- Twelve busy staff members spend numerous hours discussing whether their organization should hire a summer intern, but no one knows who has the final say, and every meeting ends without resolution.

- Several organizations work together to support a single initiative, but none of the participants understand where their responsibilities begin and end. When they disagree, no one has overall authority to decide. In addition, there’s overlap in the work done.

Do these situations resonate? If so, you are far from alone. Decision making is difficult for many reasons, including vague reporting structures and the inherent complexities of a growing organization that suddenly has to accommodate new stakeholders sitting at the leadership table.

The result is often wasted time, confusion, and frustration. Individually, everyone’s intentions are good, yet the whole performs poorly. And in the worst case, decision-making problems create a climate of mistrust and undermine an organization’s mission.

What can be done? One way to address the issue is to diagnose the source of the problem by mapping out how difficult decisions are now made. Another is to map how future decisions can be made. Several tools can facilitate these processes and help people become more thoughtful about how decisions should be made.

The Benefits of Decision-Making Tools

The core purpose of most decision-making tools is to untangle the decision-making process by identifying all activities that must take place for a decision to be made well and within an appropriate time frame. At their best, these tools give real accountability to the right people, enabling power to be shared but also setting useful boundaries. Involving the right people, while minimizing the involvement of tangential players, saves time and creates better decisions.

What’s more, by simply providing greater clarity about who is and isn’t involved, such tools can generate greater buy-in for decisions; nonprofit leaders who have experience with these tools can attest to this. “Even though there are people who aren’t involved, they’re ecstatic just to know who is involved and what the decision-making process entails,” says Joyce McGee, the executive director of the Justice Project, an advocacy nonprofit. “They feel more engaged just from understanding something that had been opaque to them before.”

This clarity can also generate additional indirect benefits. “We were able to hire higher-quality people for key senior management positions as a result of being transparent about how decisions are made,” says John Fitzpatrick, the executive director of the Texas High School Project. “I was able to sit down with top-tier candidates and demonstrate the clear lines of authority and responsibility they would have, and it allayed concerns about the chain of command and their scope of decision making.”

While most organizations can benefit from decision-making tools, they first need to look hard at how a decision-making tool can address their needs; they also need to understand how the tool they select works and assess whether the timing is right to introduce it.

Finding the Right Time and Place

Is your organization ready for a decision-making tool? To answer this question, you need to ask the following questions. (Even if your organization determines that a particular tool isn’t the right choice, the process of making that determination helps clarify how your organization functions.)

Is there is a shared sense of frustration with decision making across the organization? If many staffers believe that their organization’s current decision-making process is flawed, tools can add great value. If this concern isn’t shared, however, introducing these tools can generate more heat than light. Those who believe that the decision-making process is fine will be resistant.

Is decision making the problem? If the leadership and management team are strong but frustrated with how decisions are made, mapping tools can help. But if the real problem is a lack of leadership alignment on mission or values, decision-making tools won’t solve the problem. If an organization is in flux, it may also be the wrong time to introduce a new tool.

In the case of one organization with which we’ve worked, for example, the management team was in the midst of a massive overhaul. Suddenly, new teams were developed that hadn’t worked together previously, and team members were unclear about their roles and authority. Initially, they thought that mapping decision making would help them gain clarity. But once they began the actual process, they realized that they would need a better understanding of the organization’s new structure first.

Is the organization’s leadership ready for a tool that reveals how decisions are made? If those in power are uncomfortable about making power and roles explicit, they should not use a tool that makes these dynamics public. Many organizations function with the original founder and a familial set of relationships. Mapping the flow of power in this “family” formalizes informal relationships. If the organization isn’t ready for these kinds of changes, using a tool may be counterproductive.

Can you allow enough time to decide how to decide? Changing the decision-making process strikes at the heart of how an organization does things. As noted, outlining the decision-making process means making power explicit, which is unsettling. It may mean empowering some and taking others out of the loop. Working through various stakeholder views to get to the right solution takes time.

The RAPID Method

Organizations and teams of various sizes confronting various situations have effectively used the tool RAPID (which stands for recommend, agree, perform, input, and decide); we’ll profile that tool here.

RAPID is an acronym for the roles or activities that participants can take on in the decision-making process. Each letter stands for a specific role or activity; but participants can have more than one role assigned to them, depending on the context of the decision and the size of the group. The order of the letters is not important, but the acronym “R-A-P-I-D” is a device to remember these roles. In fact, the reality is iterative, although the roles and activities are likely to appear in the following order during any decision-making process.

- R stands for recommend. A recommender initiates the decision-making process. A recommender is the go-to person who participates in the process from start to finish, ensures that others understand what they need to do, and keeps things moving until a decision has been made.

- I stands for input. An I stakeholder must be consulted before a decision can be made. Although an I has the right to be heard, he has no vote or veto power. Including someone as an I says that an organization values her or his opinion.

- A stands for agree. An A stakeholder must agree to or approve a decision. An A stakeholder is essentially an I, but with vote and veto power (such as a CFO, who needs to approve financial decisions). Generally, the more As who are involved in a decision, the more time a decision takes.

- D stands for decide. A D stakeholder has final authority and is the only stakeholder who can commit the organization to action, such as hiring someone, spending money, or making a legally binding agreement. Generally, the D role is held by one person. But a board of directors in which each member has voting power can be a collective D as well. (Ultimately, if the committee head is a true D, it’s better to be explicit up front. Everyone knows where the power lies, anyway.)

- P stands for perform. Once a decision has been made, Ps carry it out. Often, those who are Ps are also Is.

The acronym RAPID captures a key benefit of the tool—the ability to make decisions more swiftly—but it’s important to note that the name can also suggest that decision-making processes should be rushed, which they should not be.

Side Effects and Tradeoffs

There is no denying that implementing decision-making maps and instruments can be messy. In the short term, the tool will test the resilience of the management team, particularly if it exposes an existing process that is convoluted or sorely imbalanced or reveals a complete lack of process. And its tradeoffs can make people uncomfortable.

Implementing tools like RAPID, for example, can mean trading a highly participatory decision-making culture for a faster and more efficient one. The nature of the decision determines whether the tradeoff is appropriate. Sometimes a decision is better made by consensus (where everyone is an A), or even by voting (such as requiring 51 percent of the board for a D). But most organizational decisions are best made quickly and efficiently, using one D and only a few As. Consider an executive director who needs to select and hire key staff members at his discretion. In this kind of situation, a clear, streamlined decision process is likely the best alternative.

Using decision-making maps also means trading ambiguity for transparency. Some organizations prefer to leave some control issues ambiguous. For example, what constitutes a strategic change (that needs to be reviewed by the board) versus a tactical decision that is within the purview of the executive director? In reality, each decision requires a judgment call. Someone must decide whether to move a decision into the RAPID process. Once a tool is introduced, ambiguity is no longer an option.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Lessons Learned

What follows are lessons we’ve learned in our experience with RAPID and from our observation of other organizations using RAPID.

Make the case for the tool before you introduce it. First, act like an R. Outline what you want to do and why, the process, the instrument to be used, and inform stakeholders when they will be involved. Make sure that everyone understands the tool.

Start by carving out a few key decisions. It’s great to start by tackling a handful of decisions that cause the most pain. But at the outset, don’t put more than a dozen on the list; overloading may cause the process to stall. Your organization will not miss the irony if the exercise you’ve introduced to improve decision making merely creates analysis paralysis.

Pacing is important. Tool implementation is worth getting right, so lay out a formal work plan for the process. Decisions that result in big changes need managing, so you need to know when you will make key decisions and put them into action.

Stakeholder anxiety and adjustment is part of the process. In the case of RAPID, the process of assigning roles is best done iteratively and expeditiously. But without firm leadership, managing stakeholder inclusion can be tricky, not least because people can feel excluded when they are no longer involved in decisions. Others can be vulnerable because their power is exposed. One executive director described the meeting, for example, someone asked, “So who is responsible for communicating the decision to those who aren’t involved in the decision making but still need to know the outcome (i.e., an R, A, P, I, or D)?” The executive director was quick to clarify that none of these roles had been assigned this responsibility; that decision would be made in a separate process.

Once a decision-making instrument has been used, review the whole. Take the time to get distance and see how it all fits together. Does the new way of making key decisions make sense? Do responsibilities and accountabilities match roles? Does the work balance fairly? Do you have buy-in from key leaders?

Decision-making maps and diagnostic tools can be useful even when they are not used in their entirety. As we noted earlier, after introducing a tool, some organizations use it only for problem diagnosis. Others take these ideas and build on them to create their own unique decision-making processes. And some use the tools simply to map out how prior decisions have been made.

RAPID in Practice: Aspire Public Schools

Aspire Public Schools, an organization that opens and operates public charter schools in California, initially used the RAPID (recommend, agree, perform, input, and decide) method as a diagnostic tool and then began to use it to plan future decision making. Aspire’s experience demonstrates how the tool works in practice.

Founded in 1998, Aspire opened its first school in 1999 and grew quickly; by 2006, it operated 17 schools across California, primarily serving low-income students. One of the hallmarks of Aspire’s culture was its mantra that everyone in the organization—teachers, principals, staff at the national level—was accountable for the schools’ performance.

As Aspire grew, however, its leadership team—CEO Don Shalvey, Chief Academic Officer (CAO) Elise Darwish, COO Gloria Lee, CFO Mike Barr, and VP of Secondary Education Linda Frost—came to realize that while everyone felt a sense of accountability, allocation of responsibility was unclear.

When it came to making decisions about Aspire’s high schools, the confusion was most acute. Aspire originally focused on elementary and middle schools and was successful using an outcome-based and process-driven academic model. The organization had expanded into high schools as more of its middle-school students approached high-school age. But producing top-tier educational outcomes at the high-school level presented a whole new set of challenges. High schools, for example, require curricula for many more subjects than do elementary and middle schools. And Aspire’s high school-age students had more issues influencing academic performance than did middle school-age students.

The position of VP of secondary education had been created to guide the holistic development of the high schools. But the addition of a new person to the leadership team blurred already informal boundaries concerning decision making. For example, CAO Darwish, who had created Aspire’s successful K–8 academic model and process, believed that a similar classroom model and process could work well at the high-school level. But it was unclear whether her role was to run the classroom model at the high-school level. While Frost agreed about the value of the model, she found herself swamped with school-level issues and responsibilities, such as establishing a college-bound culture, building relationships with local community colleges and businesses, and developing a standard model for the administration of the high schools in Aspire’s portfolio. Both Darwish and Frost felt responsible for success and worked extremely hard. But their positions overlapped and also left gaps in responsibility.

The leadership team believed that RAPID could help clarify these positions’ roles and responsibilities and create an organization-wide decision-making process for the future. And so, along with other members of Aspire’s steering committee, they embarked on a process, in CEO Shalvey’s words, to “decide how to decide.”

The process began with several high-level conversations with the CEO, the COO, and the CAO about what makes high schools successful. These initial conversations resulted in a strategic context for Aspire’s organizational processes. It became clear that, for Aspire, there were two different levels of success. There was success in the classroom, which included course materials, teaching methods, clear outcomes, and a process of testing and adaptation. And there was success throughout a school, which included the school’s culture and operations.

Subsequently, the COO, the CAO, and the VP of secondary education engaged in additional discussion to define the CAO and VP roles more specifically. They realized that being responsible for and making decisions about these two spheres—in the classroom versus throughout the school—required different skill sets and that these two skillsets fit naturally with the CAO and the VP of secondary education roles.

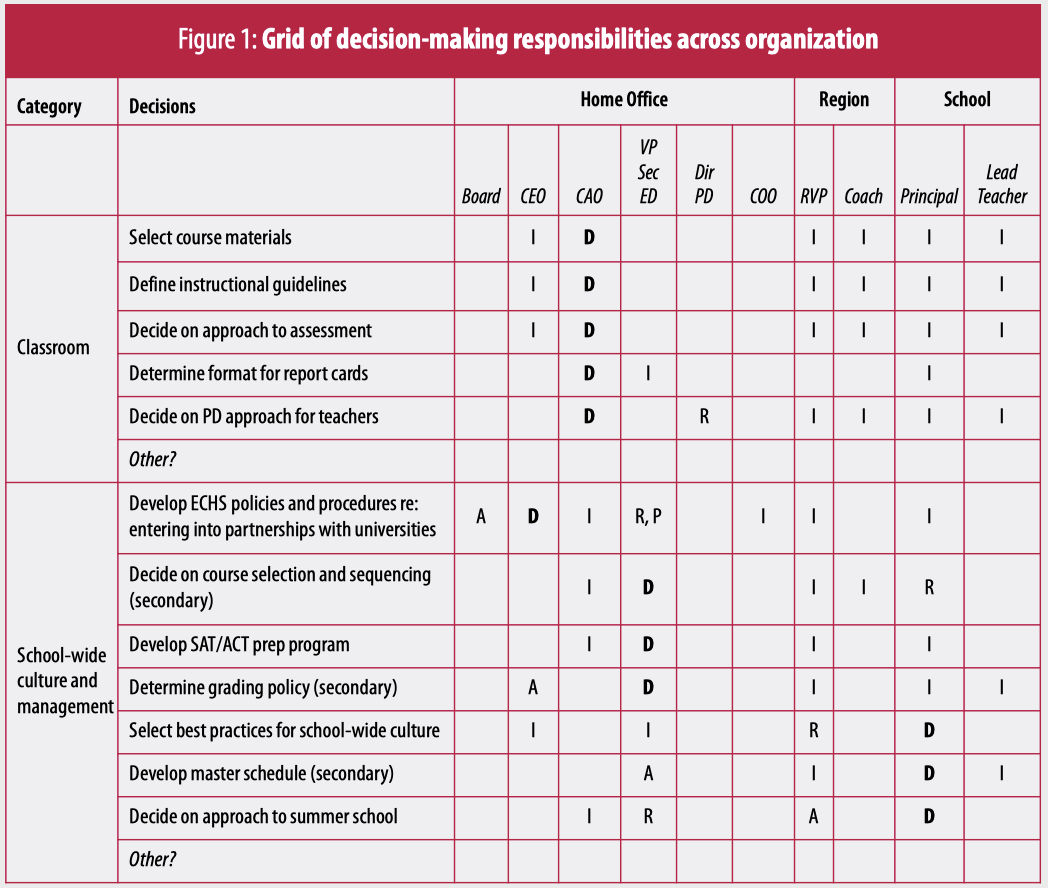

This realization led the larger team to articulate an overall “accountability chain.” The team didn’t want to lose the idea that everyone was accountable for something (and thus was a stakeholder in Aspire’s success). But they needed to create boundaries. Expressed in a chart, this accountability chain gave teachers responsibility for what happened in their classrooms, gave principals responsibility for what happened within their schools, gave the CAO responsibility for what happened within the classrooms throughout the entire network, and gave the VP of secondary education responsibility for what happened outside the classrooms within the high schools (See Figure 1). It also clarified the responsibilities and boundaries that would accompany a new layer of positions—regional vice presidents—going forward.

Once any decision-making tool is in use, the genie is out of the bottle. Much of the value comes from unveiling how decisions are made. And once roles are clear, it is hard to put things back under wraps. If your first foray with these tools is successful, however, your team will want to use them again. And if your organization is clear about where the power to make decisions sits, it can grow. Complexity can spark collaboration, not confusion. While some may feel excluded, we bet that the candor about decision making will engender respect. Your team can use its passion to strive for even greater impact.

Note

- RAPID is a service mark of Bain and Company.