Editors’ note: This piece differs from those previously published on collective impact in that the implications stem from several decades of empirical research on networks. Although collective impact is often portrayed as a relatively new phenomenon, years’ worth of network research suggest insights that may be useful to the all-important early step of determining an initiative’s common agenda. The article also elaborates on an often underexplored area of collective impact. Although some parts of the collective impact framework have gotten increased attention (the backbone organization, equity in collective impact, strategies for mutual alignment), the notion of a common agenda is often taken for granted, when in fact it poses a real stumbling block for networks in their early stages.

This article is from the summer 2016 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly magazine.

Agreeing on a common agenda is one of the chief tenets of collective impact—and one of the prerequisites for moving collaboration forward. However, our experience working with collective impact initiatives and other similar networks suggests that collective impact leaders often struggle to get buy-in from various community stakeholders in the crucial early stages. Specifically, we’ve seen that insistence on a common agenda sets a high bar, and may derail partnerships early on. More important, the common agenda may create barriers to entry for diverse partners if they hold views at odds with “mainstream” values and assumptions.

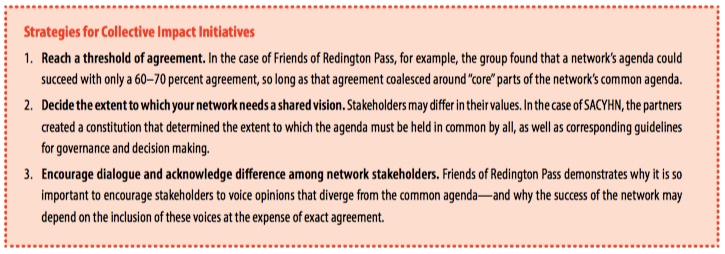

Although we agree that a common agenda is important, we suggest that collective impact leaders should treat it as an aspiration rather than a destination. We draw upon several decades of network research and exemplar networks to suggest instead that focusing on the process of creating a common agenda allows for diverse perspectives to impact the initiative’s trajectory. To that end, we identify common barriers to agreeing on a common agenda, including the “birds of a feather” tension and the “two hats” problem. We then offer suggestions for reaching a threshold of agreement that moves initiatives forward—even if total agreement can’t be achieved. There is much to be said for a principled agreement to disagree on some elements of a common agenda.

Birds of a Feather

Over thirty years of network research has demonstrated that the easiest way to form a social network is to recruit people who share a common experience based on characteristics such as race, class, gender, or education.1 This is the principle of homophily, or “birds of a feather flock together.” Because partners with similar backgrounds can relate to one another, they bond more easily than those who don’t. This means that the quickest way of building a common agenda is to rely on like-minded individuals.

This sounds dismal for those of us who value diversity and inclusion, but it needn’t be so—there is another powerful finding from network research that helps mitigate the principle of homophily: Although bringing people together in the first place is made easier through similarities, networks are more innovative when diverse partners participate. Through the interaction of stakeholders with diverse goals, expertise, and backgrounds, networks become more innovative, effective, and resilient. In other words, effective networks adopt the principles of both “opposites attract” and “birds of a feather.”

The question of which principle networks honor—and when—poses a dilemma; however, leaders should recall that dilemmas cannot be solved—only managed better or worse. Therefore, one of the most important network management tasks is balancing the need for networks to have enough cohesion to hold themselves together, but not so much that they exhibit “groupthink” that causes them to reject new ideas and practices. From the standpoint of network research, managing the “birds/opposites” dilemma is one of the keys to network effectiveness.

One way that networks manage this tension is by explicitly acknowledging and accounting for differences. For example, in research conducted on the Southern Alberta Child and Youth Health Network (SACYHN), we discovered that the network dealt with this dilemma by having two “tables.” One table included the network members in the healthcare arena who created the network (“birds”), and the other included members who had interests in education, members who had interests in social services, and members who represented diverse constituencies (“opposites”). The network acknowledged differences between the “birds” and the “opposites” by creating terms of reference that specified different obligations for the two groups. Core members, the “birds,” shared a common agenda, whereas “opposites” shared some, but not all, of those interests.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Both network evaluation and participant observation concluded that acknowledging this “birds/opposites” dilemma and creating an institutional structure to mitigate this tension was one of the keys to SACYHN’s success. Over the life of the network, SACYHN has been viewed reputationally as the most successful child and youth health network in Canada.2

Two Hats

In addition to creating a bias toward “birds of a feather,” the common agenda standard doesn’t address the “two hats” problem, which is a shorthand way of saying that members have interests in their organizations and the network. This tension can lead to hidden agendas, which are toxic in networks.

The “two hats” problem cannot and should not be wished away. Network members may be torn between their own organizational agenda and the agenda of the network itself. Network research teaches us that there are two fundamental tasks that every manager in a network must adhere to: managing the network, and managing his or organization in the network. One way to manage this tension is by creating a threshold of agreement, rather than insisting on a completely common vision of the desired outcome. For example, in rural Pima County, Arizona, a group of individuals created Friends of Redington Pass, a collaborative named for the public lands joining the Santa Catalina and Rincon Mountains. The collaborative’s first task was to recognize the legitimacy of the interests of all concerned. In this case, a common agenda took a back seat to respect for the differing interests of a group of other individuals: environmentalists, property owners, a cattle grazing permittee, horseback riders, hikers, off-road vehicle owners, and gun enthusiasts—a group with diverse views regarding conservation and availability of the Pass for recreational use. Their second task was to develop enough agreement so that they could negotiate a set of consensus recommendations to the U.S. Forest Service on how to better manage Redington Pass. In this example, recognition of the “two hats” problem was the basis for the more diverse group’s willingness to join Friends of Redington Pass and thus gain standing as a body that deserves to be at the table as a partner with the Forest Service.3

Implications of the “Birds of a Feather” and “Two Hats” Dilemmas for the Common Agenda

- The SACYHN example demonstrates that, rather than having exact agreement, it’s more important that partners speak honestly about their varying reasons for involvement in the network, and communicate clearly the degree of their commitment to the network.

- In the example of Friends of Redington Pass, people approach a common agenda with different stakes in the problem—and it is necessary and healthy to acknowledge those differences, as this discourages hidden agendas. We argue that it is better to air these differences publicly rather than keep them hidden. This allows network managers to manage the dilemma of the “two hats” in an open and frank way that views other agendas as legitimate and allows members to meet a threshold of agreement.

- Some organizations are more critical to collective impact success than others, as illustrated by the SACYHN network’s “two tables” approach. Agreement upon a common agenda may be more important for core organizations than for others.

- Some elements of the common agenda may have more relevance for the network’s success, while others may not. Group members disagreed on how open Redington Pass should be to the public (for example, the environmentalists argued for more protection of the Pass than the off-road vehicle group or the gun enthusiasts typically supported), but everyone realized that they were more powerful working together than separately to leverage their common interests for greater conservation resources to be dedicated to the Pass in the Coronado National Forest plan.

- The creation and implementation of a common agenda has negative implications for equity—there’s power not only in setting the agenda but also in forcing others to adhere to the agenda. Viewing the common agenda as a “continuing dialogue” makes it easier to encourage and accommodate diverse views as well as to make adjustments based on new information or changed circumstances.

…

Today, Friends of Redington Pass serves as an umbrella organization to bring together groups and organize events that allow and encourage shared use of the land. Their experience—and that of SACYHN—demonstrates that both common and divergent interests can be a powerful force for bringing groups together and facilitating change for those working to improve educational, environmental, or health outcomes in a collective impact setting.

Notes

- Janice Popp et al., Inter-Organizational Networks: A Review of the Literature to Inform Practice (Washington, DC: IBM Center for the Business of Government, 2014).

- Ibid.; and Robin H. Lemaire, Keith G. Provan, and H. Brinton Milward, SACYHN network analysis and evaluation report (Calgary, AB: Southern Alberta Child and Youth Health Network [SACYHN], unpublished document, 2010).

- Information in this section is from an interview conducted by Brint Milward, on May 17, 2016, with Kirk Emerson, professor of practice in collaborative governance at the University of Arizona School of Government and Public Policy, and board president of Friends of Redington Pass.