July 20, 2017; Journal Times (Associated Press)

Rules are useless if they’re not enforced. That truism is providing a handy escape for Texas-based refineries, which escape pollution controls through a combination of bad law-writing and poor enforcement by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

The Washington, D.C.-based Environmental Integrity Project (EIP) filed suits against permits for the ExxonMobil Baytown Olefins plant and refinery, the largest integrated petrochemical factory in the U.S.; Petrobras’s Pasadena refinery; the Saudi-owned Motiva Port Arthur refinery, the largest petroleum refinery in the U.S.; and SWEPCO’s Welsh coal-fired power plant east of Dallas, according to The Journal Times.

“For years, the group claims, power plant and refinery operations have polluted almost without penalty because of a loophole in Texas permits that allows for excessive emissions when machinery malfunctions or undergoes maintenance,” the Times added.

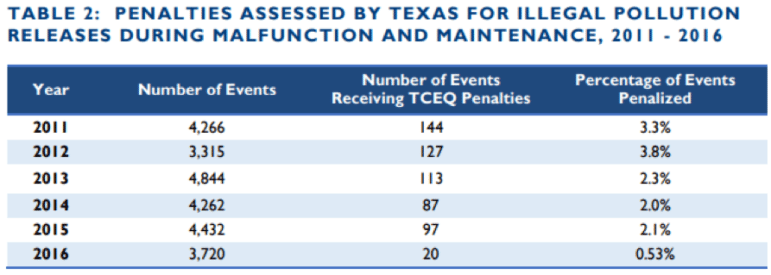

According to the EIP’s website, “The analysis of state records by Environment Texas and EIP reveals that Texas imposed penalties on only 588 out of 24,839 malfunction and maintenance events reported by companies from 2011 through 2016. The total fine for these violations of the law was $13.5 million, which averages about 3¢ per pound.” That hardly makes it worth it for profit-motivated companies to upgrade equipment or responsibly dispose of waste products.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

On top of emissions from the huge refineries, which are easy targets for environmental protection groups, according to EIP, “supposedly small sources of air pollution, like oil and gas wells, release as much pollution during equipment breakdowns as large factories, but escape factory-style regulation because they claim to be minor or ‘insignificant’ polluters.”

Enforcement of EPA standards, such as they are, has only gotten worse over the years, and the response of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality is rather pathetic. When EPI reported that only about three percent of the reported 25,000 illegal pollution cases resulted in a fine, Spokesman Brian McGovern argued that the state’s enforcement rate was actually seven percent, as if that were a defense. As EPI’s spokesman Tom Pelton pointed out, that’s a horrifying admission, “because this means the state admits it allows 93 percent of these illegal pollution incidents go without even a violation notice.”

Nonprofits have been crucial to any enforcement of environmental regulation that’s happened in Texas. The 2017 suit that penalized ExxonMobil $20 million for emitting 10 million pounds of pollutants from its Baytown refining and chemical complex was initiated not by the state government, but by the local residents working with Environment Texas and the Sierra Club.

It may be time for them to step into a more active role. The solutions recommended by EPI in the Breakdown in Enforcement Report seem fainthearted; they all depend upon more frequent inspections and stricter requirements for polluters, but what does that matter when TCEQ doesn’t enforce the regulations that already exist? Recommendation number one, for instance, suggests that violators prove that “malfunctions resulting in illegal pollution releases are not preventable before deciding not to pursue enforcement actions for penalties and cleanup.” Who is to determine what is preventable, and what will motivate TCEQ to go through even more enforcement steps when they hardly ever initiate the simpler process now?

Even the federal Environmental Protection Agency may not be much help, since, as NPQ reported recently, “the agency doesn’t seem to have a policy agenda in place” and director Scott Pruitt has not shown any interest in environmental protection. That leaves ordinary citizens and nonprofits to pay attention where environmental regulations are toothless or poorly enforced, and step in where they can. In this, we are all stakeholders, since it is our planet that suffers when standards slip.—Erin Rubin