August 4, 2015; The Guardian

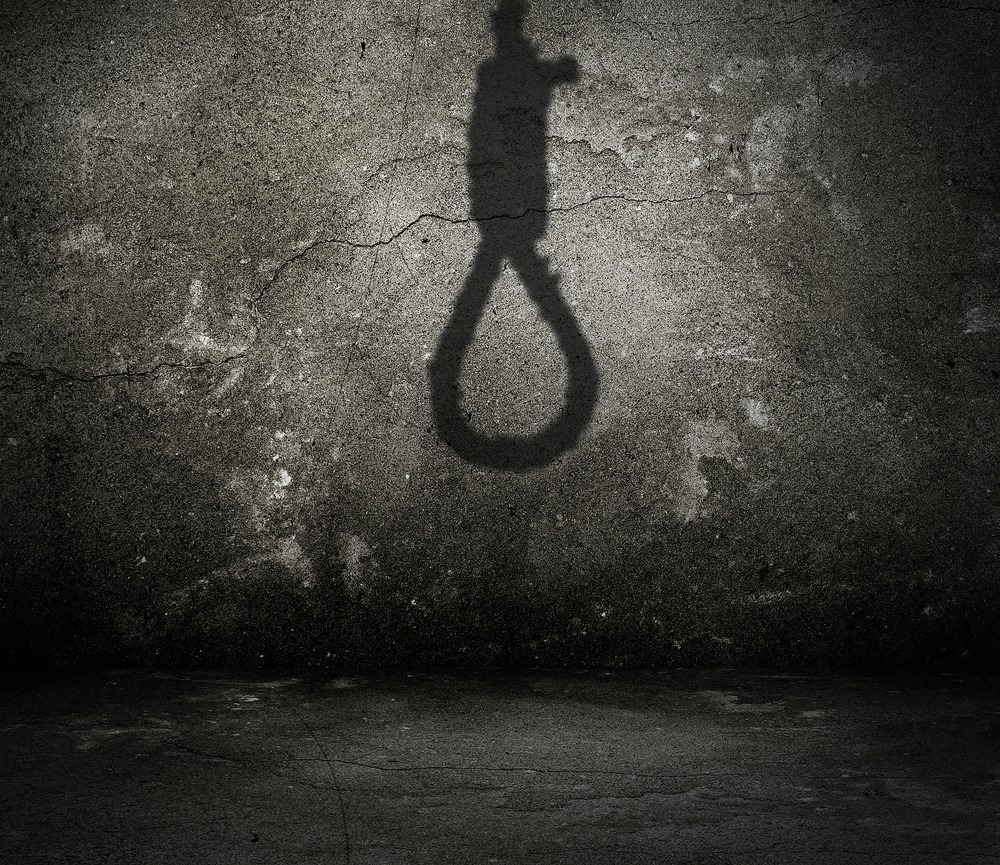

Since December, when Pakistan lifted its moratorium on the death penalty following the Peshawar terrorist attack that killed more than a hundred children, 180 people have been put to death. At that time, Pakistan had suspended the death penalty for seven years. Now, with more than 8,000 people on death row, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan has voiced concern over the pace that Pakistan is executing prisoners.

The purported reasoning behind lifting the death penalty was to allow the Pakistani government to get tough on terrorists. However, there are clear indications not just that the executions are not restricted to terrorists, but that they are too often the result of a flawed justice system. Human rights organizations and the UN have expressed outrage, but the executions continue unabated.

“We’ve seen time and time again that there is immeasurable injustice in Pakistan’s criminal justice system, with a rampant culture of police torture, inadequate counsel and unfair trials,” said Sarah Belal, executive director of Justice Project Pakistan. “Despite knowing this, the government has irresponsibly brought back capital punishment.”

One case in point is Shafqat Hussain, who was hanged Tuesday morning for a crime for which he was convicted in 2004. Hussain was found guilty of kidnapping and killing a 7-year-old boy and sentenced to death, but he and his international supporters have maintained for years that he was a teenager at the time and tortured into confessing, a claim of which Pakistani courts remained unconvinced.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“Pakistan authorities have never undertaken a proper, judicial investigation into either issue,” said the rights group Justice Project Pakistan, “instead seizing and refusing to release key evidence such as Shafqat’s school record, which could have provided proof that he was under 18 when he was sentenced to death.”

Supporters claim that Hussain was only 14 years old when he was prosecuted, a fact which his court-appointed attorney failed to bring forth any evidence at his trial. If it could have been proven that Hussain was a minor, then he would have been ineligible for the death penalty under Pakistani law. The police instead say Hussain was 23 at the time. Although it may seem simple, in a third-world country where records of births and deaths are routinely lost or disorganized, authenticating a birth certificate is easier said than done. In one hearing for Hussain, judges resorted to using pictures to verify his age.

Hussain’s execution was postponed four times alone this year, due in part to the controversial nature of his conviction. He quickly garnered support from human rights activists and groups. While Hussain was set to be executed in January of this year, Pakistan’s Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar called for a stay order to investigate whether Hussain was indeed a minor at the time he was prosecuted. Others similarly advocated for Hussain, including the human rights lawyers that took on his case, the United Nations, such human rights groups as Reprieve and Amnesty International, and the country’s own Sindh Human Rights Commission, which asked for an inquiry into the case.

“This is another deeply sad day for Pakistan,” said David Griffiths from Amnesty International. “A man whose age remains disputed and whose conviction was built around torture has now paid with his life—and for a crime for which the death penalty cannot be imposed under international law.”

There are deeper issues with the death penalty than those that can be seen in Hussain’s case. Some see Hussain’s execution as reflective of the many other wrongs in an already-flawed legal system that rushes to judgment and dispenses with justice. “The government’s decision to push ahead with the execution despite calls to halt it from across Pakistan and around the world seems to have been more a show of political power than anything to do with justice,” said Maya Foa, director of the death penalty team at Reprieve.—Shafaq Hasan