September 30, 2016; National Public Radio

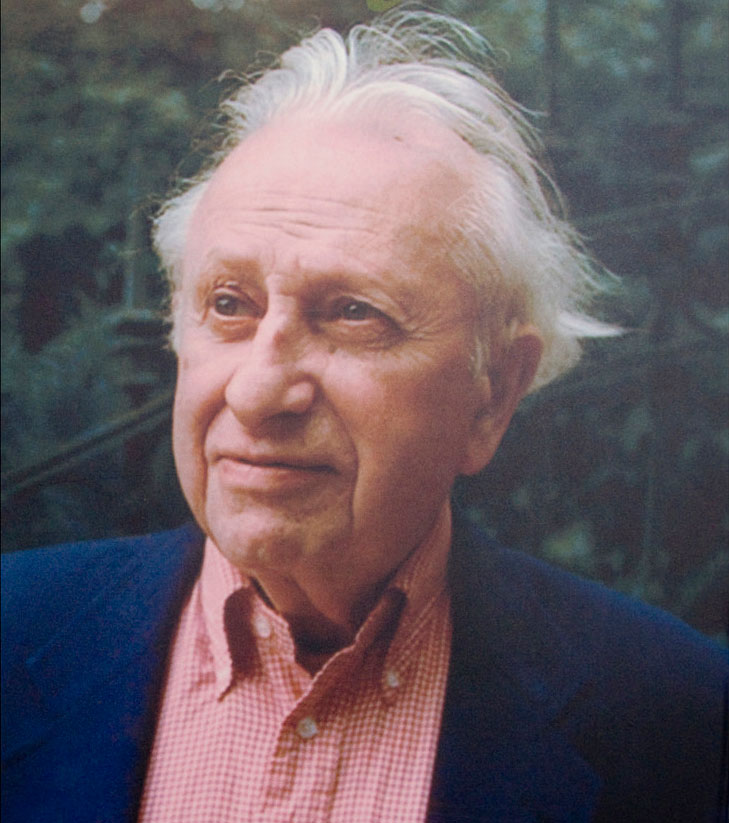

In the 1970s, author and broadcaster Studs Terkel embarked on an oral assignment to capture how ordinary Americans felt about a topic all of us can relate to—work. After conducting more than 130 personal interviews, Terkel compiled the various stories into a book entitled Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day And How They Feel About What They Do. Fast-forward to 2016; Radio Diaries and Project& have unearthed the recorded interviews and reconnected with some of the people who shared their stories with the late Terkel to revisit their feelings about their work.

While some snippets of Terkel’s conversations simply dove into the ins and outs of an average workday, like the process of a telephone operator helping a caller on the other line, others revealed a more profound connection between a person’s work and life. Renault Robinson, who served as one of the few black officers in the Chicago Police Department in the 1970s, co-founded the Afro-American Patrolmen’s League and went on to fight racial discrimination in policing. Robinson’s look back on his discussion with Terkel paints a somber picture that’s all-too-similar to how he views the same line of work today. In the ’70s, Robinson told Terkel:

Black folks or minority tolerance of police brutality has grown very short—they won’t accept that treatment, they won’t accept that dehumanizing, degrading treatment, that’s why more young kids are being killed by the police than ever before.

Robinson’s frustration is still appropriately intact today, telling NPR in 2016, “Whether it’s Chicago, or Baltimore or Detroit, the same thing is happening in all of these cities. It just feels like déjà vu.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While stories like Robinson’s remind us of an unfortunate lack of progress in certain areas, others illustrate how the past four decades have helped shape a much different American workforce. Forty years ago, the workforce held dramatically less diversity and opportunity for certain demographics. In the early 1970s, the rate of participation in the workforce among women stood at 38 percent, and though it has been slow to grow for at least the past two decades, women represent roughly half of the working population today. At the start of the ’70s, women earned 40.6 percent less than their male counterparts; some 40 years later, the pay gap has slowly closed to approximately 20 percent.

While the advancement of women in the U.S. workforce has made gradual gains, other populations have yet to see similar growth. A 2015 New York Times article reported that although the number of black Americans in executive and managerial roles has risen, the unemployment gap has remained stagnant over the last 40 years and income and wealth gaps between white and black Americans have in fact widened. Disparities do still exist, with the number of managerial and executive positions held today by the same type of worker too closely resembling the workforce back then and the proportion of earnings between male and female workers hardly catching up with the times.

The role of technology in work is perhaps the most significant juxtaposition between the workforce of the 1970s and today. A recurring theme in Terkel’s interviews was the fear that machines would someday replace workers. That question is just as relevant today as it was 40 years ago, as modern technology continues to evolve at a pace that would have been unimaginable decades ago.

In 2016, work in America is as hot a topic as ever. Whether the discussion is wages, unions, women in the workplace, or an intergenerational workforce, work remains an omnipresent and important preoccupation. Just like in the 1970s, work connects us all, even though the playing field remains uneven for many. And yet despite the political disconnect and social inequities that influence a person’s work, many workers—then and now—continue to pursue work that has greater meaning than a paycheck. As Terkel himself once said, “[Work] is about a search, too, for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash, for astonishment rather than torpor; in short, for a sort of life rather than a Monday-through-Friday sort of dying.”—Lindsay Walker