Editors’ note: Bill Ryan, well-known coauthor of Governance as Leadership: Reframing the Work of Nonprofit Boards (Wiley, 2005) turned his attention two years ago to a study of coaching. The study was commissioned by the Haas, Jr. Fund in California, and examined the methods and results of coaching within its Flexible Leadership Awards (FLA) program. Coaching is a short- to mid-term consultation designed to help a leader improve work performance, and was an integral part of the FLA program. In his report Coaching Practices and Prospects: The Flexible Leadership Awards Program in Context, Ryan documents not only the experiences within the FLA but also the fact that coaching is in increasingly widespread use in the corporate sector, to help further develop both emerging and seasoned leaders. Is it just the latest fad or an existing practice renamed . . . or is it an exciting new idea to integrate into our talent development practices? NPQ editor in chief Ruth McCambridge explored these and other questions with Ryan. (For those interested in a full discussion of coaching, we highly recommend the report, which can be downloaded here and can also be found on the Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund website, www.haasjr.org.) This article was originally published in the summer 2011 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly.

Ruth McCambridge: If coaching is the answer, what’s the question?

Bill Ryan: The question is, “If my organization wants to get to Point X, how am I, as a leader, in the way, and what do I need to do to get out of the way?” That’s a negative formulation of it. Another way to put it would be, “If my organization wants to get to Point X, what do I, as a leader, need to do to build on my strengths and manage my weaknesses to help it get there?”

RM: It was interesting to see in the report how vague and all over the place the definitions of coaching are. Can you talk a little bit about what people mean when they talk about coaching?

BR: There are lots of people attempting to nail down the definition. The practice of coaching is still relatively new, so everyone is trying to definitively type it, and, in particular, they’re very anxious to distinguish it from consulting or therapy. Some people, invested in the practice as a profession, want to put coaching on the map as something highly distinctive.

RM: But isn’t it kind of a weird combination of consulting and therapy?

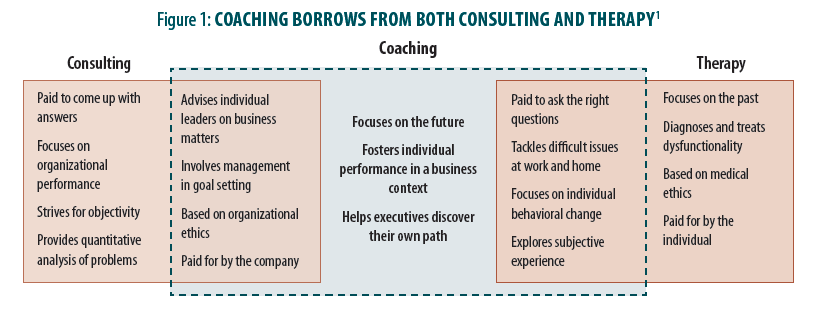

BR: That’s right—when I talk to coaches and they describe what they do, it reveals that they’re doing a blend of things, and there was a nice typology put together by editors at Harvard Business Review that did show the overlap [see Figure 1].

I think, probably, the big difference many are trying to emphasize is that consulting would be about trying to come up with the answer, therapy would be about trying to get to self-understanding by understanding the past, and coaching is in the middle.

[Coaching] should help you gain enough introspection to come up with your own solutions looking toward the future. [Leadership guru] Warren Benning was quoted as saying, basically, that the effort to distinguish it from therapy is partly just to make it more legitimate. No manager, certainly no for-profit one, is going to say, “I’ve got to stop our meeting now, it’s time for me to meet with my shrink.” But to say, “It’s time for me to meet with my coach” would be acceptable.

RM: In the report you talked about people using the term to refer to three different types of practice.

BR: When I interviewed coaches, and also spoke to “coachees,” and listened to what they did rather than how they describe what they do, three versions started to come into focus.

Version one is coaching as a profession, and that’s the way it’s described in the literature. So, these are “true” professionals who offer coaching to executives as their full-time job, and they have certification by a coaching accrediting authority of some sort.

More common among nonprofits are the people who are doing coaching as a practice. They may do this either full- or part-time, but the people offering the coaching are basically consultants who are drawing on their past experience in the nonprofit sector, maybe, and a specific skill set or perspective, but they don’t identify as professionals. They’re not certified. They don’t necessarily favor certification. This is something they’ve discovered they’re effective at, so they offer it.

The third practice I thought quite interesting, and I described it as best I could as coaching as perspective. This is where either managers or consultants (who could be strategy or fundraising consultants) consciously take a coaching stance in their work. So, their core work as a manager is actually reshaped by their understanding of coaching. Instead of telling people you supervise what to do and what you expect, you’re trying to help them think their way through the problem. You’re asking them, “What do you think, exactly, is the roadblock or the problem here? What were your first thoughts about coming to resolution?” You’re not only helping them arrive at a good answer, but it’s actually developmental; it’s really much more about helping them do things over time. How do you sustain that development over time? That’s what coaching as perspective is about.

RM: You suggested that some worry that there are organizations using coaching to outsource their management, but does the use of coaching always require that the coach be external?

BR: Say an executive director doesn’t really have the interest, the inclination, or the capacity to actually supervise a direct report, help that person develop, confront weaknesses. What they sometimes do is get a coach to take that work on. Now, there are different ways of looking at that. You can say, “Gee, that’s really not a good thing, that work is essential to management, and the ED in that case should just step up, learn how to do it, and do it.” But the other way is a bit more realistic. Some EDs are never going to get there, and as one of my interviewees said, “Look, if it works and it’s a relatively modest investment, what’s wrong with it?”

But your original question was, does the coach have to be outsourced? And I would say no. These coaching stances can be used internally, and some organizations have gotten quite carried away with this [approach]. I think it was Deloitte—the accounting consultancy—who a few years ago aspired to be what they call “the coached organization,” where everyone was developing and supporting their talent internally by consciously taking a coaching stance. It need not be [outsourced], and a lot of people would say it shouldn’t always be outsourced. If you have the skills and the capacity internally, it could be better to have people inside the organization coach each other.

RM: You said somewhere in your report that the coaches sometimes seem to be “outsourced suppliers of candor.” Is bringing in a coach just a less messy way to supervise somebody who is difficult?

BR: I think that that may be true, and I think that goes back to jargon, you know, “coaching as management.” I think it’s true that hiring an external coach can be a way of ducking the responsibility of helping a subordinate figure out the underlying reasons he or she is stuck. So, to me, that avoidance would be troubling. That would suggest that the person who’s overrelying on coaching to manage reports could probably benefit by some coaching herself. The question being, why does she not want to step up to the challenge of giving negative feedback or holding someone accountable? I wouldn’t say that’s the most prevalent pattern here, but I certainly think it’s something to keep an eye on.

I think this also relates to what I think I had called the “triangle.” I’m not sure how true this really is, but in the literature and by the accounts of people in corporations, the idea is that there’s a kind of three-way or triangular team. So, you’ve got a subordinate, a boss, and a coach. And, the idea in this model is that the boss is helping the subordinate identify some areas for development that are going to help that subordinate achieve some goals pertaining to his unit or the organization. So, there’s already been a conversation between a boss and a subordinate that says, “Okay, here’s where we’re trying to get, here’s where you seem to need to develop yourself.” Or, “Here are some weaknesses you’ve got to manage your way around. Now, here’s the coach who is going to help us do that.” This type of arrangement establishes a real goal and sense of accountability. The coach is not going to come and divulge everything she’s heard from the subordinate, but there will be check-ins along the way: “Boss, how do you think this is going?” “Is the behavior different?” et cetera. And, that’s very different from just having someone in an organization have a coach, who knows nothing about the organization’s reality—what it might do, how the person is perceived—and then just working with them on self-understanding.

RM: But many coaches claim confidentiality in the same way that a psychologist would claim confidentiality. How does that work in such a triangulation?

BR: I think any good coach is going to protect confidentiality. But I think what can happen at the outset is that a context can be set so there are some expectations that will help the coach focus the coaching and keep in mind where it is the “coachee” is trying to get. Number one is the context. The check-ins can be a way for the coach and “coachee” to hear how progress looks from the outside. And one of the riddles here is, “Wow, this stuff is so nuanced, so difficult to quantify and measure, how do we keep an eye on progress?”

You check in once in a while. You refer back to the goals originally set, and you might hear from a boss, “Okay, here is how I see it happening, here’s what’s going on,” and then the coach and the “coachee” think about the feedback, and that might inform their next steps.

It doesn’t compromise confidentiality but it does try to keep the coaching attached to organizational goals, because that’s what it should be all about. It’s not just about developing a leader—it’s about developing a specific leader in a specific place with specific challenges, and trying to gain an understanding of how to change behavior that will pull that all together.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

RM: But it does raise the question, “Who is the client?” Can you talk a little bit about that, because that seemed to me extremely confusing.

BR: I think it is confusing, and I’m not sure there’s a way to make it very tidy. I think coaches will say, “Okay, we feel accountable to the ‘coachee.’ ” That’s the most common pattern in the nonprofit sector. You don’t normally see, for example, a board bringing in a coach and having that conversation and then working with the ED. So, really, it’s a one-on-one. Those coaches are going to feel, “My client is the ‘coachee.’ ”

In the corporate sector, the coaches are going to feel, “This person is my ‘coachee’ but my client is the company.” Often they’ll be coaching more than one person, they work for HR, they’re part of an initiative, it’s very much driven by the business objectives of the company. So, what they’re saying is your division needs to increase market share, it needs to grow, it needs to reduce turnover of staff. You’re responsible for that. You know, we’re going to help you skill up—soft skills. We’re going to help you be a better leader to do that. But that is the pure business understanding of these relationships. That’s exactly what it is that the coaches are brought in for: to support the company’s business objectives by helping its individual leaders contribute better toward those goals.

RM: In the report, you suggested that business is less concerned about return on investment for coaching than those who would fund coaching in the nonprofit sector. Why would that be?

BR: Here’s my understanding of this (and I think you read my observation correctly): in business, purchasers of coaching are less worried about proving the impact of coaching than nonprofit funders of coaching would be.

For example, I think one of the studies reported that only 13 percent of businesses that hire coaches actually try to calculate any kind of ROI, strictly speaking: “This person got coaching and she reduced staff turnover by that percentage, and that saved us that money, and therefore one coaching dollar produced three dollars in benefits.” There are some firms that will try to do that, but the number is small—13 or so percent. That’s one stance.

The other stance tends to accept that there are just some givens. Here, the general practice of coaching is accepted as more or less plausible. Talent makes a difference; therefore, supporting talent makes a difference. Helping individual people understand how they work and improve their individual leadership will also probably make a difference.

Now, that doesn’t mean that those people aren’t concerned about the performance of coaches and the benefit of coaching, but they tend to have all of that in place and use the triangle model we discussed, where they’re trying to look at an individual’s performance related to specific goals they set together. And then they can start making a judgment on whether the coaching is working or not. There’s the pure ROI model, and there’s this “plausible judgment” model.

What I have encountered among nonprofits and foundations is a little different, where the question tends to be not “Is our investment in coaching paying off?” but much more abstract: “Does coaching work?” And that’s just something that’s not really asked in business, per se. In business, it’s “Does our coaching program for our people pay results for us?” That’s very different from “Does coaching work?”

They’re trying to ask for an answer to this global question on the nonprofit side. On the business side, they’re just trying to figure out “How do we make it work for us?”

For example, if funders are going to make a grant for strategic planning, they generally wouldn’t say, “Okay, give us the evidence that strategic planning works.” There is no such evidence. At some point, these things just get accepted—perhaps they shouldn’t be—as a tool in the repertoire.

I would encourage people investing in coaching to just be as thoughtful as possible about figuring out how to make coaching work in their own situation, and be really rigorous and systematic about what they can get their arms around, rather than try to figure out “does coaching work?”—unless they’re in a position to fund huge empirical research.

RM: As I looked at your graph about where coaching seemed to work well, I saw that one of the areas was executive transition, which in many organizations may mean the coaching of an older person on how he or she is going to build leadership capacity in the organization, et cetera. But then you also had in the report a lot about how business was looking at its use with younger employees. So, it’s almost like there’s an emphasis on two sides of the sandwich.

BR: Yeah. I think there’s some broad overlap. I just have a narrow view into this, obviously—I’m not sure what’s going on across the nonprofit sector, but in the cases I looked at, what I saw in [executive] transition was coaching to help an older leader make decisions about “how long is my tenure, how long do I stay here, how do I get ready to support the organization for my exit?”

It just also happened to be the case that a lot of the “coachees” I tried to learn from were participating in this program Flexible Leadership Awards of the Haas Fund, and a lot of them, in fact, were new EDs, and the coaching for them centered on, “How do I master this new role? What are my blind spots, what are my gaps, what do I need to figure out to jump in and succeed here?”

In general, though, the tone in business tends to be very much focused on the development of younger talent—by no means exclusively, but it’s understood that this is a good developmental resource. A lot of people in that field make the argument that new workers—whatever generation they would be at this point, let’s say Gen Y—expect a lot of feedback, support, counseling, encouragement. And you may look at that and say, “Well, they’re spoiled brats. Why should I throw coaching on top of it?” I think businesses look at it and say, “This is just the reality. If we want to attract and retain that talent, this is how these folks work, and this is one way of adapting to supporting that group.”

RM: Given the small size of most nonprofits, the lack of mobility within a single organization may mean that as you’re developing somebody, you’re developing their capacity beyond where their strict job description has them sitting. A lot of leadership programs in the nonprofit sector focus on individual leaders, develop them, and then the leaders leave the organization. The development of an individual leader can result in the organization’s losing that person. What do you think about that?

BR: That’s an interesting question. I guess my observation would be that there are two ways of supporting talent. One is to invest in someone’s general development—for instance, “You’re going to go to this nonprofit management institute, we’re sending you to these workshops, et cetera.” You’re really expanding someone’s repertoire in a way that they can also put on their resume and which makes them more marketable. There’s always a concern, and a feeling that if we invest all this in you, we want a commitment that you’ll stay and not run off with the new skills.

The same may be true of coaching but I think

the risk might be lower, because if it’s put together thoughtfully it is not just going to be a general way of becoming more effective as a leader or a manager; it’s pretty much anchored in a specific context. Given that we’re looking at coaching as a resource, hopefully it has those benefits of making better leaders in general, but that’s not necessarily the primary goal. [Coaching] is very context driven. I don’t know if that means that with coaching you would actually see less people getting skilled up and becoming more marketable and leaving. But I think there is that distinction related to being anchored in a specific context. This is a very hopeful view of it. I guess overall you hope there would be enough investment in coaching across the sector that that type of mobility would wash out.

RM: Is there anything else you would say about the coaching you’ve observed? Do you have any caveats? Anything that you would say not to do in the name of coaching?

BR: I think I would emphasize the importance of thinking of coaching as an initiative, like a project—particularly if you’re a funder who is going to help a number of people do coaching, but also if you’re an ED and you’re able to provide coaching. It’s not just about grabbing a coach and pairing him or her off with someone who needs help. It’s really trying to think through those initial questions of “What are the needs of the organization?” and “What kind of talent potential do we have on hand?” I think it’s also important to identify good “coachees.” Some people are at the right moment and have the right mindset to benefit. Some are either at the wrong moment or have the wrong mindset, and the investment wouldn’t be a wise one.

NOTE

- Carol Kauffman and Diane Coutu, “The Realities of Executive Coaching,” HBR Business Report, Harvard Business Review, January 2009.