As it turns out, the online giving revolution has not been televised. But it has been Facebooked. In fact, it may be less revolution and more evolution. Whether it comes quickly or slowly, individual giving online has definitely increased.

Giving USA estimates that in 2009 more than $227 billion was donated by individuals, but estimates of how much of that number is now contributed online vary widely. Blackbaud produces an index of 1,710 nonprofits of various sizes and business models and indicates that, on average, online revenue has increased more than 20 percent in the three months that ended in August 2010. Despite that large number—and the number has been on a substantial trend upward for years—Blackbaud reports that its indexed online revenue accounts for only about $406 million annually, which is a small fraction of total charitable giving.

Starting early with online giving and scaling later provides advantages, but don’t ramp down your traditional giving strategies just yet. Indeed, some innovative organizations have used Web-based transaction tools and social media to help boost their giving numbers. These increasingly trusted giving methods have helped lower the barriers to entry for new donors, encouraged existing donors to continue to give, and connected these groups to a wider network of engaged donors. While enhanced giving with Web-based methods is still in its infancy—and can easily be subject to hype—some have begun to see how these tools can do more than raise money. They have also successfully connected organizations more closely with their donors.

Anyone who has rued the day he turned down a purchase of the initial Google stock offering can vouch that getting started early can make a big difference in a meteoric rise. It is simply more important to understand how much can be invested in future growth and how much is needed to keep current donor relations alive and well during the transition.

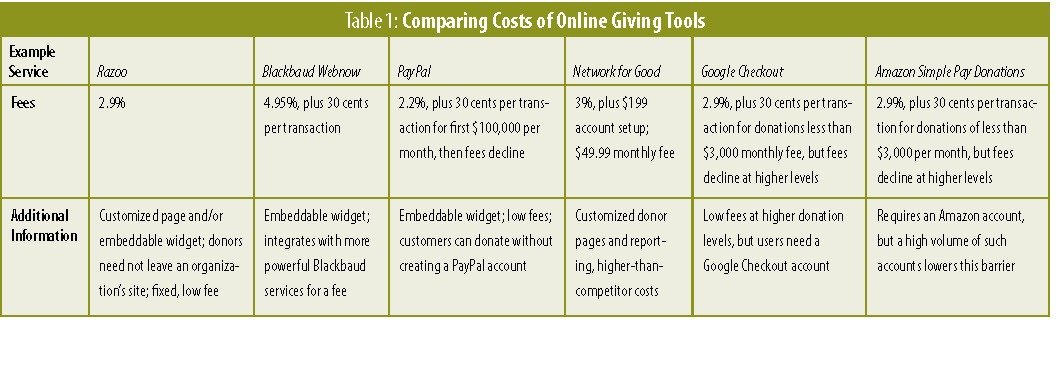

But unless nonprofits take an incremental approach, Web-based transaction tools can get pricey quickly.

A group of philanthropic groups in Minnesota recognized the barriers to entry associated with online giving sites. The Minnesota Community Foundation and others created GiveMN.org, a portal site for nonprofits to use free services to accept online donations. The site was originally launched with Network for Good’s software for transaction processing, with the foundation and corporate support to underwrite processing fees. Capabilities on the rest of the site, such as the ability to create customized donation pages for each nonprofit, were powered by Razoo. The result: nonprofits on GiveMN.org retained 100 percent of the donations made through the site at launch.

Table 1: Comparing Costs of Online Giving Tools – Click to enlarge.

GiveMN.org remains committed to providing an easy point of entry and now uses Razoo to provide transaction processing through U.S. Bank, as Razoo powers other site features. Razoo pre-populates the site using data from the IRS Form 990 reports. Any registered nonprofit organization can go to the site, search for itself, and “claim” its identity. Once verified, a nonprofit can use Razoo to build a donations page with giving levels, pictures, video and more. For smaller nonprofits, the page may in fact be their only Web presence, says Dana Nelson, the executive director of GiveMN.org. “One of our two main objectives is to build capacity for the nonprofit sector to help [organizations] understand the trend, why this is important, and then we serve as that on-ramp to the Internet,” Nelson says.

Razoo and Network for Good are only two of many options for organizations to delve into online contributions. As online giving levels increase, and as staff familiarity with the technology improves, a tighter integration with fundraising software through services such as Blackbaud may show the right return on investment. Until then, there are several choices to keep costs low while organizations explore this new service with their donors.

In November 2009, GiveMN.org launched with its Give to the Max Day event: a single-day donation drive designed to encourage nonprofits to try the site’s service. The drive made available up to $50,000 in matching funds for nonprofits that used the site. Funded by the site’s collaborators, the incentive match was an experiment that was originally envisioned as a first-come, first-served match to drive nonprofits to participate. “We raised over $14 million donated to 3,400 organizations in that 24-hour period,” GiveMN.org’s Nelson says.

But the success of the single-day campaign diluted the match pool. Rather than the starting proposition of nonprofits getting 50 cents on the dollar until the funds expired—which, given the unexpected donation levels that day, would have happened very quickly—GiveMN.org changed the premise just before the day of the drive, It ultimately decided to share the match with all participating organizations. The result was roughly 4 cents on the dollar in matching funds—rather than the original 50 cents—for each participating nonprofit.

The flood of donations taught two powerful lessons: (1) incentives to act immediately matter to donors, and (2) be careful what you wish for in providing incentives. There was one day—and only one day—during which organizations could apply for matching funds. Unprecedented levels of participation prompted some nonprofits to voice concern about the rules having changed so late in the game and some potential new donors to view the drive as a disorganized campaign. Uncertain about the changed match, some nonprofits continued to communicate the unchanged rules until the deadline.

It’s difficult to get reliable information on the number of donations that came from existing donors that gave early to meet the match, compared with the number of donations from new or increased donations. GiveMN.org and many other participating organizations did not track the funds generated by the drive. “We don’t have hard data. We’re going to measure more this year,” Nelson notes.

Give to the Max Day 2010 won’t offer matching dollars as an incentive for donors to act, but the collective marketing behind the endeavor will likely create a competitive sense of urgency within the community. Many nonprofits will reach out to donors simultaneously, creating a need to respond by a specific date. Also missing this year will be the donated processing fees that were part of the first Give to the Max Day. In 2009, the donated processing fees were a larger gift to participating nonprofits—in total dollars—than the match itself.

And to add fuel to the fire, Give to the Max Day will also hold a contest among organizations to drive the largest number of donors (not necessarily the most dollars). Every hour, one donor will be chosen at random to receive a $1,000 matching pledge to its cause. Each of these ideas helps drive the need to decide and act.1

GiveMN.org isn’t suggesting all the incentives come from it alone. The site promotes independent matching pledges from participating organizations’ existing supporters to bring in new energy through online channels. Each effort adds to others in creating a need to make the donation online, now, rather than wait and possibly not make the donation at all.

As foundation and corporate philanthropy continues to change, nonprofits such as Big Brothers and Big Sisters of Central Minnesota are still adapting to changes in revenue. Shari Whalin, Big Brothers and Big Sisters’ development director, has felt the pinch of declining revenue and has turned online for better ways to connect with new individual donors. In the process, she’s found a new way to connect with existing supporters as well.

“We think the number of new donors is mixed with existing donors using online giving,” Whalin says. Using Give to the Max 2009 as a starting point, Whalin and other supporters of the organization augmented the GiveMN.org site with small, individual efforts. They e-mailed existing supporters before the campaign began so these potential donors would be ready for the 24-hour drive. Each staff member was asked to include Give to the Max Day information in the signature line of every e-mail message he or she sent. Communications that didn’t specifically concern fundraising brought added urgency to the campaign. The organization used its Facebook page to spread the word virally and asked willing supporters to “like” the effort, thereby posting the information in the newsfeeds of other users who weren’t yet connected to the organization.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

But Whalin wasn’t going to let electronic communication limit the organization’s outreach and its potential for matching funds. “We sent perhaps 60 to 70 letters by postal mail, and we made phone calls to existing donors encouraging them to act for Give to the Max Day matches,” Whalin reports. The need to act by a deadline ensured continued support and helped spread the word to new donors.

As useful as the GiveMN.org site is, it still can’t do everything in donor relations and development. “We have our Bowl for Kids’ Sake event, but we can’t use GiveMN.org, because we need to charge participants and GiveMN.org doesn’t support that,” Whalin explains. Big Brothers and Big Sisters still uses online resources—FirstGiving.com in this case—to get their bowling teams registered and paid. That event collects more money online than via paper, and the trend is growing.

Part of what drives new donors is the relevance of the donation request. Requesting general-operating support is great, but a specific value proposition works in the world of clicks just as it does in the world of bricks. “Say there’s an organization working with young people at back-to-school time,” Nelson says. “Creating a project page that has a deadline around the start of school with targeted dollars to virtually donate a backpack [the dollar amount equivalent to allow the program to buy the pack] is very practical. It can generate a lot of new donors because they can give a fairly small amount.”

Blackbaud may have reported double-digit growth percentages in total online giving, but for younger demographics, the numbers skew much more heavily toward online donations. The Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project reports that more than 73 percent of young American adults use social media as a primary means of gathering information and decision making—and that includes where and how to give money. For this group, micropayments and small donations are an easier point of entry, and traditional wisdom holds that once a donation relationship has been established, successful charities have a much stronger opportunity to raise new dollars later.

A challenge for the development community, however, is understanding how to build this new relationship. Once an online donor is listed in the database, there is a natural temptation to send that prospect a regular-mail solicitation;? four pages, different-color fonts, and a large P.S. message after the signature line. Given its online preferences, however, younger recipients may be put off by physical mailings and assume that the charity doesn’t understand their needs and, in turn, discontinue this emerging relationship rather than respond to it.

Instead of reaching for the landline telephone or a preaddressed envelope to maintain and strengthen a relationship that started online, a more successful strategy may be to provide content value to a donor in his native space. Post a video to Facebook and YouTube (yes, in both locations) with details on how donations made a difference, then engage the potential online donor as a marketing advocate. With services such as AddThis.com—which provides a one-click way to share a Web site throughout several social-media platforms—it’s easy for nonprofits to enlist donors as partners in finding more supporters.

Katya Andresen of Network for Good emphasizes the importance of good old-fashioned communication in the online donor space. “This isn’t an ATM,” Dana Nelson says, paraphrasing Andresen. “You can’t just have this one-way interaction where you’re e-mailing people asking for money all the time.” Just as your paper solicitations can land in the recycling bin, your online requests may be more easily sent to the recycling bin or, worse, the spam folder. When building an online donor relationship, you need to use your donor site and tools to tell the story of how you make a difference and not just ask for money. Most of these donor sites can embed photos, for example, sharing the success of your campaign or demonstrating your need. You can also provide donor feedback by listing donors on the site, which builds a sense of commitment and urgency.

As much as existing nonprofits can’t simply enter a PIN and get back money, emerging nonprofits can’t go to established sources of funding and turn around a major grant in no time. Newer nonprofits—or new programs of existing nonprofits—may need twenty-first- century thinking and agility to meet costs and demonstrate success before they can be considered for larger, traditional funding.

The online venture Kickstarter is designed to provide new or startup funding for any venture. It can be a for-profit or nonprofit or an unincorporated company. The idea is to demonstrate a specific idea and set a minimum dollar amount needed to get that idea off the ground. Donors can pledge to a project, but if the project doesn’t reach the minimum amount needed before the funding deadline (no more than 45 days, often less), then no pledges are collected and the project folds.

Jeff DeBruyn, the cofounder of Imagination Station in Detroit, recounts his organization’s effort to get a new project funded online without using traditional nonprofit infrastructure. “We were outside the usual suspects” in terms of which organizations were funded by traditional donations and grants, he recalls. “We use a lot of volunteers but still had some costs. We decided to ask for $2,011 as a symbolic number for our work in razing a building.” Online donors outside the Detroit neighborhood served by the emerging Imagination Station were grateful to hear of work to support their former community, and pledges came in exceeding the goal. “I only sent five e-mails,” DeBruyn explained. “Others sent more, but we got to the goal ahead of schedule and stopped pushing on that project so we could focus on the next phase.” Imagination Station may request another Kickstarter project in the future—all projects have to be approved to participate in the site based on Kickstarter’s own criteria for appropriateness and likelihood of success—but for now, the organization is encouraged by how quickly online donations can get it the cash it needs.

Two substantial advantages for online work are speed and decentralization. It is, after all, why the Internet was built. Acting early to take advantage of quick response can mean the difference in millions of dollars of revenue for important nonprofit work. “There was an ice storm in South Dakota the same week as the earthquake in Haiti,” Nelson recalls. “The Bush Foundation asked if we could post it on GiveMN.org. Then Keith Olbermann on MSNBC did this scathing piece on how nobody knew about the storm and the devastation” because attention was focused on Haiti. “One of [Olbermann’s] staffers did a search and came across the matching page on GiveMN.org, and we raised $248,000 in 24 hours.”

When crisis strikes, or when a current media message stirs interest in an older problem, the nonprofits poised to accept help are those most likely to get it. Rather than quickly rushing to build a donation site to respond to need, using existing infrastructure meant the Bush Foundation could capitalize on an opportunity it didn’t know was coming. Sending a postal appeal weeks later, or even a phone call days after the event, simply doesn’t have the same impact as a donor being asked to give as soon as he hears about the need.

As any fan of history can tell you, the true speed of change never matches the original hype. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey promised us regular commercial flights to space 10 years ago, and we’re still waiting. The hype of online donations may be greater than the reality, but the trend line has clearly increased. Nonprofits wanting to seize the opportunity to build new, dynamic relationships with individual donors have the tools to begin accepting this new partnership in funding. But don’t pack up your mailing labels and event tickets just yet. The corporate sponsorship of your YouTube channel won’t quite make up the difference in lost revenue until our self-driving cars get in from Detroit.

1. For an update on Give to the Max Day 2010, go to www.dev-npq-site.pantheonsite.io.

Copyright 2010. All rights reserved by the Nonprofit Information Networking Association, Boston, MA. Volume 17, Issue 4. Subscribe | buy issue | reprints.