While diversity, equity, and inclusion, or DEI as the terms are collectively known, are discussed at almost every philanthropic gathering, what accompanying action is needed? Are these the building blocks destined to historically reshape the foundation playing field? Or are they just the latest foundation fig leaf for inequitable practices that started with the birth of the paternalistic, charity mindset?

“We have to be honest about the sources of wealth and how wealth was accumulated in this country—a great part of it was on the backs of people of color, and now those communities are benefiting from just a very small percentage of dollars,” writes Edgar Villanueva, a respected expert on social justice philanthropy. “Once you know, how can you not be equitable about how you’re distributing the money?”

The two of us have engaged in a series of cohort-based learning efforts with foundations of differing budget sizes, funding priorities, geographic areas of focus, and leaders on almost every level of a foundation organizational chart. Since last year, we have engaged foundation presidents and CEOs through the Presidents’ Forum on Racial Equity. These leaders, whose foundations control 15 percent of all US philanthropic assets, have participated in a series of in-person sessions and webinars that center racial equity in their professional development. As one participant said, “I’m trying to understand my own white privilege from a foundation where we are the recipients of extreme white privilege.”

The following are six leadership imperatives (and guidance for navigating them) for leaders who want to lead in ways that center racial equity and justice.

1. Don’t be a leader in name only

A leader has to be vulnerable, open, and actively engaged. Racial equity work is hands-on and requires co-ownership with board and staff. As Equity in the Center says, leaders must “model a responsibility to speak about race, dominant culture, and structural racism both inside and outside the organization.”

“You can have a conversation about diversity and never talk about racism. My staff needed to see me show up and be present in that space,” said one president.

The way forward

The biggest failing of internal racial equity efforts is that the leader is not seen as deeply engaged, vulnerable, and highly participatory with staff on every level.

This is a space where it is acceptable for the CEO to not be the lead content expert in the process. Still, staff members are hungry for the executive to set the tone in this space. We hear from early-stage leaders that they do not have time to be heavily involved in this type of work, while their more seasoned counterparts know that internal racial equity processes are as mission critical as strategic planning. One leader said, “I haven’t arrived, but I’ve certainly agreed to go.”

This can be challenging for a CEO who might herself be seeking answers, but it can be done. Practical steps include developing the leadership team with clear intentions, communicating about who leads the process and about when and how goals will be set, using cultural competency assessment tools like the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI) to establish a baseline, and then measuring progress intermittently.

But even more than practical leadership, emotional leadership is critical. The CEO should be accessible, deeply engaged, and the lead point of accountability. This includes being present and focused during meetings, expressing vulnerabilities and asking for help, being patient and responsive to the frailty of others, and otherwise signaling to colleagues that this work is mission critical.

When executives put themselves fully in the racial equity space, staff will follow.

2. Prepare for the mess

We live in a country with a history mired in structural racism. Because of this, few spaces exist where people can have honest, productive conversations around race and ethnicity. Though equity work is messy, it does not have to be dysfunctional. It will be disruptive. It will shift all internal dynamics and relationships with external stakeholders. It will surface tensions, frustrations, and resentments.

Yet it can be done intentionally and skillfully.

Centering racial equity and justice can result in deeper, more authentic relationships. It can bridge some of the deep chasms among us, and usher in far more power-balanced relationships between the sector and underrepresented populations.

“Our definition of leadership in white dominant culture is that one person decides what should be done,” said one CEO. “Leadership also comes from outside the ‘leader’ and there are examples of where leadership exists inside and outside of our organizations. Part of our role as leaders is to shift to see leadership outside of us.”

The way forward

The core problem in many organizations is what Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun have termed “white supremacy culture.” The traits they say to watch out for in organizational culture include “perfectionism, a sense of urgency, defensiveness, valuing quantity over quality, worship of the written word, belief in only one right way, paternalism, either/or thinking, power hoarding, fear of open conflict, individualism, belief that I’m the only one (who can do this ‘right’), the belief that progress-is-bigger and more, a belief in objectivity, and claiming a right to comfort.”

To address and ameliorate white supremacy culture in an organization, leaders need to recognize its traits in the way they personally operate and the way their organizations work. They must get their minds around the characteristics of the culture they are seeking to overturn.

Too many organizations spin their wheels for a while through internal fixes that focus on information sharing and awkward discussions about contemporary issues rather than delving into the embedded culture. At times, these exercises result in new nicks in old wounds.

Avoid the pitfalls of leaning solely on internal expertise or looking for highly motivated people in the organization to shoulder the load. You will need to have external support if this is to work.

3. Understand the dangers of white supremacy culture

White leaders and staff need to do their own work together. Most of them will be uncomfortable in the process, but discomfort is important for growth. If white leaders, board, and staff do not spend a majority of their time in a place of discomfort, the process is not rigorous enough.

Be conscious of a default mindset that centers whiteness in every activity. People of color already experience varying levels of discomfort every day in most organizations. Rather than placing the weight of racial equity-related organizational change on their shoulders, organizational leaders should make intentional efforts to develop the racial equity muscles of staff based upon their overarching and distinctive needs of how whiteness is experienced.

This means setting aside time for white people to ask questions and fulfill their curiosities among themselves. White staff members enter the process seeking information, clarification, and validation that they are decent people who are trying.

“I could sense the power of the racial caucuses. It was helpful to me to hear my story and reflect without having to be highly self-conscious about how it would land on the other side,” said one leader.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In mixed settings, these sincere inquiries can be triggering and undermine trust with indigenous people and people of color, who come into equity processes with distinctly different needs. They are often seeking space to be seen, heard, and validated in the context of ongoing offenses based upon their racial and intersecting identities. It is especially important to honor these needs by applying equitable support for them.

“The thing that is unsaid in our foundation right now is an aspect of whiteness. Almost since the time I took the job, there’s politeness, fear, and avoidance, and when I ask people to talk about it, there’s huge pushback,” offered one CEO.

People of color are all-too-often exposed to white fragility-centered training sessions that are painful and are not provided time and space for their own healing and safety. When done skillfully, race-peer conversations can be invigorating and a pathway to significant change.

The way forward

CEOs must cultivate a healthy internal culture for all staff. As one president said, “Organizational culture is ‘the way we do things around here,’ but much of it is invisible and shapes profoundly what we do and don’t do.” One way to move toward this is through regularly scheduled meetings that include caucusing by race. Breaking out staff by race has proven effective in helping organizations make progress.

Societally, we all need space to process the impacts of whiteness. In work settings, these spaces need to be crafted to allow for honesty and relate-ability. Different racial groups have different needs for self-disclosure, healing, and progress.

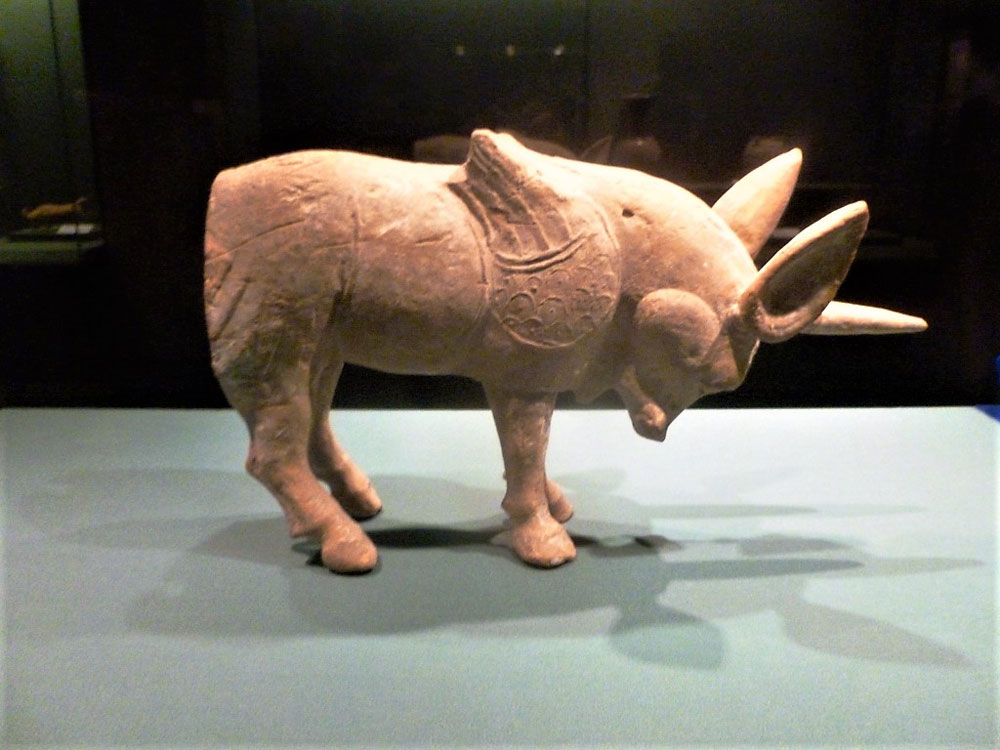

Other options include deep engagement in places of significance to the process (e.g., museums) as well as skill-building sessions around topics such as identifying and analyzing the root causes of racial inequities and how to set racial equity goals to track and measure organizational progress.

4. Do not rely on unicorns—either in staff or in processes

Also unhelpful to organizational change is over-dependence on highly motivated and accomplished “unicorns.” The term “unicorns” emerged from the technology industry and refers to those rare people with the ability to wear many hats and excel at varied tasks.

Leaders must ensure that people of color are not treated like workplace unicorns only around racial equity work and must avoid putting them on the frontlines of the change process without sufficient cover. If the leadership does not pay extremely close attention, people of color within the organization will carry a disproportionate burden of creating organizational change in racial equity processes. One person said, “The burden for some of our staff of color of constantly being in the space of code- switching. What is my responsibility and role?”

Another unhelpful practice is disproportionately stacking racial equity explorations with junior staff. This sets the stage for committee outputs that do not stick because the members lack clout.

Staff members of color cannot be expected to serve as the explainers-in-chief of all things racial equity. White people often think they do colleagues of color a favor by deferring to their “expertise.” It is, instead, an exhausting burden that may burn out these staff members faster than overt racism, especially for those staff members who are young, junior, and eager for change.

The way forward

Confront organizational norms that reinforce tendencies toward unicorn culture, perfectionism, worship of the written word, and excessive reliance on urgency. Then determine the new norms that will replace them.

As Jones and Okun say, “Many of our organizations, while saying we want to be multicultural, really only allow other people and cultures to come in if they adapt or conform to already existing cultural norms. Being able to identify and name the cultural norms and standards you want is a first step to making room for a truly multicultural organization.”

Cultivating an internal culture that values multiculturalism and brave space is essential. This can be done through identifying sources of power and race inside and outside the organization and holding regularly scheduled and facilitated meetings centered on topics that build skills in giving and receiving feedback.

5. Recognize the need for racial equity—in your organization, the sector, and the world

Most white people are still uncomfortable when confronted with the reality of white supremacy culture and their role in reinforcing it. Without deep learning around US racial history and the ability to see the powerful institutions and structures that support and maintain racial inequity, philanthropy is doomed to continue making the same mistakes, leading to the same inequitable outcomes.

The way forward

Lifting up the leadership imperatives around race is the hardest, most unskillfully addressed factor. When the racial equity expertise of top leaders is not explicitly addressed, silent suffering and unarticulated resentments tend to permeate an organization, roiling beneath the surface.

Centering racial equity is not a skill set. It is a progressive way to move an organization from diversity to inclusion and finally to equity and justice. For leaders to be effective, centering racial equity must touch every aspect of the organization’s identity and functioning.

As philanthropic leaders attempt to move their boards and staff through this process, the strengths and limitations of the existing organizational structure invariably surface and the need for improvement at the CEO and board level becomes clear. Those who want to be racial equity change makers must show up as brave leaders rather than dutiful managers. One leader asked, “What is the disconnect between the policies and practices and culture and how do you move beyond that? I think it’s about building trust and allowing people to be honest with one another from all sides. The policies may read well, and the practices may seem useful, but if you start having conversations with your employees, it may be very different.”

6. Engage with a spirit of discovery and joy

Racial equity work can cause a lot of discomfort because it challenges the dominance of whiteness in philanthropy’s norms in board appointment, hiring, investment strategies, grantmaking, and definition of impact. Making space for the contributions of other racial and ethnic groups is uncharted territory. As such, it can be far too easy to approach the culture change from a place of sadness, fear, or anger.

The way forward

Be curious and strategic, patient and urgent. As one president offered at a recent Presidents’ Forum meeting, “Our racial equity lens approach should be discovery, and that is a joyful thing. A racial equity lens should allow us to see one another, and that discovery should be joyful. There is so much anger and divisiveness surrounding race in our country. How can we turn this into a joyful thing? How do we show within the institution that we control what we would like to see in our nation as a whole?”

This work is messy, hard, and worthwhile. Developing strong leaders who center racial equity in their organization is the surest way to unlock the human capital that has been enslaved for hundreds of years by racial terror and oppression.

Getting to the heart of America’s original sin: racism

“At the heart of America’s history is this original sin of racism. How do we get at the heart of the issue, acknowledging this tension?” asked one Presidents’ Forum participant.

CEOs have different opportunities to gather with their peers at sector-wide meetings and content specific meetings around diversity, equity and inclusion. Many CEOs reported that they had attended multiple trainings within their own organizations on DEI-related skills. What they do not often have access to is planned conversations and problem-solving around what was called “this delicate issue” of being the internal leader to which staff and board look. As one participant said, “We are all the only one in our organizations who fill this space between board and staff, and we have no one to talk to many times.”

One CEO pointed out the growth needed for the sector. “There are tons of foundations in this country who have never had a conversation about race. We need to meet people where they are and start from there. I have a lot of grace from a family foundation board that has never talked about race.” For such CEOs, following these six leadership imperatives, we believe, is a good place to start.