This article comes from the summer 2011 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “Working Concerns: About Nonprofit Talent.” It was first published online on April 21, 2014.

Even before the “Great Recession,” nonprofit leaders were told that they needed to learn how to do more with less. The field encouraged nonprofits to tighten their belts and look outside their organizations for solutions. Convinced that these approaches were not the only way, the authors, as part of a “Leadership Learning Community” (LLC) team organized by the TCC Group, worked with leaders of twenty-seven civic participation organizations from 2008 to 2010 to explore an alternative: building shared leadership within an organization.

The Initiative

Strengthening Organizations to Mobilize Californians, a capacity-building initiative funded by the James Irvine Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, supported a “Leadership Learning Community” (LLC) that included peer exchanges for executive directors and senior staff, regional trainings, and comprehensive convenings. TCC Group, a national management-consulting firm, designed, managed, and facilitated the initiative. The twenty-seven participating organizations each started out with annual budgets ranging from $500,000 to $2 million; at least five staff members; eight board members; and one hundred volunteers.

After two years of experimentation with shared leadership, TCC Group conducted an evaluation, and found that 78 percent of participants had increased their awareness, knowledge, and ability to develop staff as leaders at all levels of the organization. The evaluation, which included event feedback surveys, a post-initiative survey of all participants, and two participant focus groups, also revealed significant increases in both staff involvement in decision making and clear and effective accountability structures throughout the cohort. Many of the organizations discovered that they were able to do more effective work with less or the same amount of funds, and reported that shared leadership eased the stresses on executive directors. Essentially, the organizations found that they could do more with less (funds) by doing more with more (leadership).

I. Shared Leadership…It Sounds Good, But What Is It Exactly?

Theories about organizational transformation have been pointing in the direction of shared leadership for more than three decades now. Experiments with “self-managing” work teams proliferated in the 1980s. In 1990, Peter M. Senge published The Fifth Discipline and popularized the concept of “learning organizations,” which called for leadership rooted in the roles of steward, teacher, and designer guided by continuous development of a capacity for understanding, action, and responsibility.1 In 1994, Jack Stack made waves with his book The Great Game of Business, where he championed the value of practicing “open-book management” and engaging workers at all levels in an ongoing process of innovation in the private sector.2 In 1999, Margaret J. Wheatley wrote in Leadership and the New Science, “Western cultural views of how best to organize and lead (now the methods most used in the world) are contrary to what life teaches. Leaders use control and imposition rather than participative, self-organizing processes.”3 And, in 2003, Joseph A. Raelin coined the term “leaderful” in his book Creating Leaderful Organizations, which describes an organization that intentionally creates the structure and culture needed to share leadership among staff, board, volunteers, and other stakeholders.4

In 2006, researchers Beverlyn Lundy Allen and Lois Wright Morton defined self-organization as the capacity that organizations need to solve the complex or “adaptive” problems they face today. One of the principal dimensions of self-organization they named was deeper diffusion of authority and responsibility into the organization.5 In 2007, Leslie R. Crutchfield and Heather McLeod Grant posited in Forces for Good that effective organizations share leadership across staff, board members, and external networks.6

Despite this dramatic shift in leadership theory, our combined research and experience with nonprofit organizations reveal that most organizations continue to accept a hierarchical structure, with the executive director shouldering an enormous burden of responsibility for organizational success. The LLC participants generally reported that this was true of their organizations. However, we found that this concentration of power was not because executive directors were power hungry. Nor was it even deliberate. It was due to a lack of familiarity with the alternatives. The executive directors were interested in exploring ways to empower staff through more formally shared leadership, given their growing fatigue and their commitment to promoting values of community engagement and empowerment. Senior staff, feeling stretched thin and yet underutilized, were also invested in this change, viewing it as a way to advance their careers and develop other staff in a manner that aligned with their organizations’ social justice values.

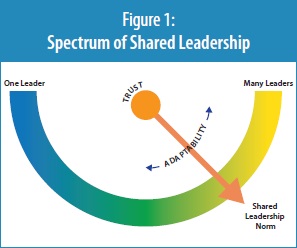

We came to understand shared leadership as encompassing a spectrum between more authoritarian models, which focus on one leader, and more inclusive models, which focus on the leadership of many (see Figure 1). We also discovered that there are dozens of ways leadership can be shared once authority is expanded beyond an individual position to the group—without fully ceding authority to that group. Among the participating organizations, authority—over what, with whom, and through which structures—varied significantly. However, three characteristics were common to all the organizations:

- Adaptability within the Spectrum. Knowing when a particular expression of leadership is appropriate, and being able to shift within the spectrum as needed.

- Orientation toward Shared Leadership. Expanding the problem-solving capacity of an organization without giving up the option of top-down approaches when necessary.

- Culture of Trust. Developing the relationships needed to shift within the spectrum when necessary, without any negative impact or mistrust.

Adaptability within the Shared Leadership Spectrum

Adaptability means being able, as a group, to occupy the right place in the spectrum for each situation. In a presentation to the participants, Ken Otter, Director of Leadership Studies at Saint Mary’s College of California, used the analogy of maps to illustrate this point. If one is in New York City and needs to get from Brooklyn to Staten Island without a car, a public transportation map is useful; if one wants to understand how public health resources are distributed in New York City, one needs a different map. Similarly, an organization needing to terminate an employee may need to use a top-down approach. When developing a new program, however, leveraging internal resources and external relationships is likely more useful. To achieve the best results, we need multiple maps and the ability to know when to use which one.

Orientation toward Shared Leadership

Shared leadership requires that staff be willing to see the big picture and take ownership for the whole organization. An executive director cannot decree this orientation; nor can it take root without senior leadership. A shared leadership orientation is more of an invitation for all staff to assume greater responsibility and influence. Not everyone wants this, however; occasionally, staff members will leave the organization when this approach is implemented. But if shared leadership does not become a broadly shared orientation, not much change is possible.

Trust as a Foundation for Shared Leadership

Shared leadership requires some trust, and then tends to increase trust. Allen and Morton, Patrick Lencioni, and many others underscore this point.7 The first step takes a certain leap of faith: “Will my staff follow through?” “Will my executive director give me room to try new things?” The participants reported that taking these sorts of risks helped build trust among staff and allowed for more flexibility to shift along the leadership spectrum. They also identified several helpful practices, including aligning values, clarifying accountability, explicitly supporting experimentation, and consistently working toward clear communication.

II. Prerequisites for Shared Leadership

Shared leadership requires a certain amount of individual and organizational maturity. The most successful participants started with four common characteristics (see Figure 2):

- An explicit commitment by senior leadership to change;

- An up-front investment of time to educate and plan;

- Fundamental management practices in place; and

- Engagement and accountability.

These characteristics provided the necessary foundation to support a shift toward shared leadership. Moreover, they tended to feed one another in a “virtuous” cycle, where improvements in one area led to improvements in others. When any of the characteristics were not present, we found that it was more difficult—if not impossible, depending on how many characteristics were missing—to achieve much change.

Desire and Commitment to Change

Designating at least one “champion” to encourage staff to take time to reflect, define problems and generate solutions together, articulate a common vision and agreements, and work out disagreements helped lay the groundwork for developing shared leadership. Each organization we worked with cultivated this commitment in different ways. At the Center for Community Advocacy (CCA), a farm workers’ rights organization, the executive director championed the idea of shared leadership and brought others along. At ACCESS, a women’s health justice organization, a senior staff member was introduced to the concepts and recruited the executive director to experiment with shared leadership. Meanwhile, the Alliance for a Better Community (ABC), a community-building organization, used its ten-year anniversary to discuss how to strengthen its capacity to implement the programmatic changes needed to deepen impact. The executive director and associate director then presented ideas to the board, and the board supported the effort.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Up-Front Investment of Time

Cultivating shared leadership takes significant time, and most likely reduces efficiency in the short term. After all, it involves changing (often increasing) the frequency and duration of contact among staff, shifting the nature and quality of these interactions, and developing the systems and structures that will sustain these changes. However, when faced with such complex challenges as the need to increase impact using fewer people and dollars, the time spent up-front helps organizations respond more effectively and efficiently.

At the end of the initiative, participants reported having saved time through improved problem solving, especially by generating alternatives that would not have been thought of by the executive director alone. Some also gained organizational efficiencies, as work responsibilities shifted and staff morale and satisfaction improved. Moreover, developing shared leadership often went hand in hand with a focus on “continuous improvement”—the drive to be more efficient and effective.

Fundamental Management Practices

Without the basics of organizational management in place, experimenting with alternative approaches to leadership is risky. The basics include appropriate supervision, effective communication and decision making, and having a clear strategy, sound financial management systems, and ongoing mechanisms for planning and allocation of work. These basic systems do not necessarily need to be exemplary, but they cannot be so problematic that a focus on leadership will not be sustained and supported. In fact, some of the participants used a shared leadership approach to improve their organizations’ basic management practices. The Environmental Health Coalition (EHC), for example, engaged a team of staff leaders from every level of the organization in planning for an all-staff retreat to develop the standards of a healthy, leaderful organization. At the other end of the spectrum, two organizations that attempted to shift responsibility to senior staff experienced problems because of unclear roles and responsibilities. When this happens, organizations need to stop what they are doing and work on basic management practices before continuing with their effort.

Engagement and Accountability

Senior leaders cannot be loners. Part of their responsibility is to actively work with other staff leaders to figure out how to make systems work better. This dimension of the job description must be explicit, and something for which people are held accountable. At East LA Community Corporation (ELACC), leaders within the management team met regularly to discuss how to engage all staff throughout the organization in leadership. Leadership responsibilities became part of job descriptions, were discussed at regular supervisory meetings and performance reviews, and were integrated into trainings for new and newly promoted employees. As a result, managers became more confident in their roles and shifted their departmental culture so that staff no longer expected the executive director to resolve all their challenges.

But sharing responsibility does not always make things better. Sometimes the “right balance” means less sharing. If an individual is unable or unwilling to handle leadership responsibilities, the executive director must recognize this and transparently limit the authority and discretion of the individual. At one organization, for example, the executive director found that too much independence and discretion had been given to program directors. To bring back order to the management team, the director quickly created sharper boundaries around roles and responsibilities. This meant a decrease in some staff’s ability to exercise leadership independently—at least temporarily.

III. How Did Participants Put Shared Leadership into Action?

While each organization found its own path toward putting the shared leadership concepts into practice, we found a few common themes:

Transformation in Mindset and Role

Participants transformed their self-conceptions of their roles as organizational leaders, and developed new skills to fulfill those roles. In particular, they grew to understand their responsibility for creating a culture of engagement and accountability across the board. These leaders pursued training, coaching, and self-reflection to build their leadership skills, and brought these skills and tools to all staff.

Having made the mental shift, they could also leverage existing processes to cultivate shared leadership among other staff. For example, ELACC’s executive director began by engaging staff in the annual budgeting process and decision making. As another example, senior staff at the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy (LAANE) began with long-range planning that involved all staff in goal setting. These small steps had a large impact on the organizations, helping staff look at their organizations holistically, and raising expectations around and interest in cultivating even greater shared leadership. This led to other inclusive processes, such as larger leadership teams and regular staff meetings to reflect on results and discuss decisions.

Organizational Restructuring

Several groups began their shared leadership efforts by restructuring their organizations. East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice adopted a codirector model. Groups like LAANE created and expanded management or leadership teams. Others, like ABC, redefined staff positions and roles to create associate director or similar positions. Both LAANE and ABC also went through a process to develop shared metrics of success for teams and individuals. These performance standards made it clear that each individual was responsible for leadership; that the entire staff was responsible for defining, achieving, and evaluating success; and that programs and departments were interconnected.

Changes in Communication and in Decision-Making Processes

Participants began with sound management, communication, and decision-making processes. With new structures and more leaders, however, these protocols needed to be revisited and institutionalized across the board. Most participants adopted one or both of two frameworks—peer coaching and crucial conversations—that were introduced to participants to help structure their conversations regarding feedback, problem solving, and conflict resolution.8 Participants used these frameworks to surface unspoken issues and generate agreement around solutions. Some organizations adopted other communication standards with similar success.

Restructuring decision making was quite challenging for some of the participating organizations. Developing common criteria, clarifying who got to make what types of decisions, and following a consistent process for decision making was difficult for two reasons: first, staff were used to deferring to one or a few leaders; second, these leaders were used to making “bigger” decisions. Nevertheless, organizations overcame these obstacles and found ways to share decision making. For instance, the Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment (CRPE) held an all-staff retreat to discuss criteria for evaluating programs and deciding which campaigns to cut, expand, or start, all of which became part of their ongoing program development process.

Changing Organizational Culture and Relationships

Organizations that successfully diffused authority and responsibility underwent significant shifts in organizational culture and intraorganizational relationships.

At LAANE, for example, staff developed mutual respect, trust, and accountability among leaders and all staff through an intensive, deliberate process. LAANE began with a staff retreat to develop a vision for shared leadership, and has since engaged in strategic planning, conducted staff trainings on supervision and meeting facilitation, developed written protocols and procedures, hired a human resources director to provide executive coaching, and expanded its leadership team. Who is involved in decision making, on what issues, and why has been made much more transparent. This has encouraged staff members to offer suggestions, question assumptions, and voice their concerns, and has fostered an environment in which disagreements are not taken personally, mistakes are used as learning opportunities, and decisions are open to dialogue and debate.

IV. Reflections on the Value of Shared Leadership

While shared leadership has always been an integral part of CCA’s organizing model, I learned how to share power but maintain authority, how to communicate and listen so staff are making decisions, and how to transform CCA [into] an organization replete with meaningful delegation, which has provided a positive environment and cohesive sense of morale within the organization.

—Juan Uranga, Center for Community Advocacy

Developing shared leadership takes focus and energy. Despite the economic and political climate, most organizations participating in the initiative were able to create the structures, processes, and relationships that foster systems thinking and leadership development across all staff. These organizations’ leadership capacity has expanded, because multiple leaders are responsible for advancing the organization’s mission, leaders are more comfortable soliciting and using suggestions from others, and they are more likely to work in partnership with others, both inside and outside their organizations. This reduces the stress and potential burnout on the part of executive directors, while helping to advance, develop, and retain other staff. The result is a healthy working environment that is aligned with democratic values of inclusiveness, participation, and empowerment. In many cases, shared leadership has also led to programmatic changes, and many of the participating organizations are beginning to think about how to expand the concept of shared leadership to their boards and allies.

Notes

- Peter M. Senge, The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of the Learning Organization (New York: Currency /Doubleday, 1990).

- Jack Stack, The Great Game of Business: Unlocking the Power and Profitability of Open-Book Management (New York: Currency /Doubleday, 1994).

- Margaret J. Wheatley, Leadership and the New Science: Discovering Order in a Chaotic World (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1999).

- Joseph A. Raelin, Creating Leaderful Organizations: How to Bring Out Leadership in Everyone (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003).

- Beverlyn Lundy Allen and Lois Wright Morton, “Generating Self-Organizing Capacity: Leadership Practices and Training Needs in Non-Profits,” Journal of Extension 44, no. 6 (2006): article no. 6FEA6 .

- Leslie R. Crutchfield and Heather McLeod Grant, Forces for Good: The Six Practices of High-Impact Nonprofits (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007).

- Allen and Morton, “Generating Self-Organizing Capacity”; Patrick Lencioni, Overcoming the Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Field Guide for Leaders, Managers, and Facilitators (San Francisco: Jossey- Bass, 2005).

- Authenticity Consulting and CompassPoint provide training in the art of peer coaching. VitalSmarts provides training in the art of crucial conversations.