“FOCAL POINT” by Kevin Sloan/www.kevinsloan.com

2014 finds low-profit limited liability corporations (L3Cs) registered in North Carolina in something of quandary. Governor Pat McCrory signed a law last June making North Carolina the first state in the nation to repeal the statute authorizing L3Cs. That leaves only eight states (and two Indian nations, the Oglala Sioux and the Crow Nation of Montana) chartering L3Cs. The last state to approve L3C legislation was Rhode Island, in July of 2012. Regardless of where one stands on the concept of L3Cs, there is little debate that the momentum has slowed.

It may be as attorney with the Stoel Rives law firm and publisher of the blog LLC Law Monitor Doug Batey observed, on the occasion of the North Carolina reversal: “With serious questions being raised by academics and business lawyers, one has to wonder why the states are rushing to adopt L3C legislation[. . . .] The business lawyers and professors are analyzing and criticizing the L3C structure, the non-profit community and other promoters are pushing the L3C law hard at a local level, and state legislatures are passing the laws. But the issues raised by the commentators are apparently being ignored. This is not a good way to make public policy.” Batey concluded, “There are clearly substantial problems and issues with the current form of L3C law that the states are adopting. The existing L3C laws should either be taken off the books or changed to address the problems, and new laws in the current L3C form should not be passed.”1

Was Governor McCrory responding to structural or legislative drafting problems built into the L3C law, or, as Forbes writer Anne Field attributed to L3C adherent (and self-proclaimed originator of the L3C concept) Robert Lang, was McCrory’s and the legislature’s decision due to the right-wing political trend that has enveloped North Carolina?2

In the highly polarized politics of the United States, it is always possible to find perspectives from the political extremes weighing in on most issues. When North Carolina’s House of Representatives voted down a law to authorize benefit corporations, WRAL’s capitol bureau chief, Laura Leslie, mentioned that the legislation had been subject to what its sponsor, Republican representative Chuck McGrady, called “web chatter”—that the movement for benefit corporations was, according to Leslie, “part of a secret conspiracy to promote the United Nations’ ‘Agenda 21’ sustainability efforts,” and therefore a “socialist plot.”3 This was after the benefit corporation legislation passed North Carolina’s Republican-dominated state senate fifty to zero.

Notwithstanding the political dramatics, the problem for L3Cs looks to be less conspiratorial and more pedestrian: there appears to be a disjunct between their purported reason for being and how they actually function.

Why Be an L3C?

The simple definition of an L3C is an entity that is allowed to make a (limited) profit but is committed to pursuing a charitable purpose. And to look at any state’s list of L3Cs, it is not difficult to imagine, at least by their names, that they may indeed be, fundamentally, entities established to pursue charitable activities but which, due to the simplicity, brevity, and minimal oversight from state agencies, have established themselves as L3Cs instead of public charities. In other words, they opted for the L3C instead of the 501(c)(3) as their preferred vehicle. Why would anyone opt to forgo eligibility for charitable donations and instead register a charitable activity as an L3C? One answer may be that by becoming an L3C, these charitable entities bypass the tasks, and legal costs, and annual filings and disclosures required of 501(c) tax-exempt entities.

Even at the height of the Great Recession, although many established nonprofits were suffering from extreme shortfalls in charitable donations as well as government contracts, new nonprofits were constantly being created—and with little evidence that the Internal Revenue Service’s review constituted much of an obstacle. Encouraged by any number of enthusiasts devoted to promoting social enterprise, there is something of an ethos in that sector that suggests that with a good heart and creative spirit, notwithstanding limited capitalization, you too can be a social entrepreneur. In fact, getting approved for tax-exempt status by the IRS is, by the looks of things, as simple as getting a cup of coffee. And this seems especially true with respect to L3Cs: states request relatively little information from L3Cs in terms of applications and reporting, and appear even more willing to hand out L3C approvals than the IRS is vis-à-vis 501(c)(3)s. Indeed, it isn’t particularly evident that, given the remarkably limited information required by states that have authorized L3Cs, there is much that would cause an L3C applicant to earn a rejection.

As with tiny charities that sometimes barely exist—and after a period of time lose their tax-exempt status for not managing to file even a Form 990N e-postcard—some of these L3Cs fall by the wayside, presumably as their founders or organizers realize just how tough it is to make their vision of accomplishing a charitable purpose a going concern. That said, interSector Partners, L3C, counts a thousand active L3Cs in the nine states and, in the Oglala Sioux nation, four entities that have opted for the limited profit model as opposed to the public charity structure—although it is conceivable that some of these L3Cs might have some sort of affiliation with existing 501(c)(3)s or 501(c)(6)s.4

L3Cs in Action: The Mission Center and the VSJF Flexible Capital Fund

Notwithstanding their currently uncertain status, L3Cs can be found operating across the nation—registered in one state, where they were first authorized, but pursuing activity wherever their missions take them. Given the range of charitable missions L3Cs may pursue, the types of functions and services they can take on are potentially as diverse as those of public charities—different only in that they are meant to be services delivered in a for-profit environment. The Mission Center (TMC) and the VSJF Flexible Capital Fund (Flex Fund) are two examples.

An L3C located in midtown St. Louis,5 The Mission Center provides “back office” services and support to nonprofit organizations6—typically accounting, human resources, and insurance functions that small nonprofits may not have the scale and desire to obtain on their own but could afford if obtained jointly through this type of business incubator. Established only recently, in 2010, TMC describes itself (in all caps) on its website as “THE NATION’S PREMIER SOCIAL ENTERPRISE INCUBATOR AND ACCELERATOR.”7 TMC may be young but it boasts a “board of advisors” membership of well-known people: the aforementioned Robert Lang; John Tyler, general counsel of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation; Phillip Fisher, principal of Michigan’s Max and Marjorie Fisher Foundation and founder of The Mission Throttle L3C; and Barbara Levin, chair of the board of Nonprofit Missouri, the state’s nonprofit trade association. TMC’s ability to attract such a high-level coterie of advisors suggests that these persons of significant philanthropic and nonprofit experience view the L3C as a serious and legitimate organizational form for the accomplishment of charitable purposes.

But TMC’s services are not a line of business unique or restricted to L3Cs. In both San Francisco and New York, the nonprofit foundation Tides provides shared office and back office services to a mix of some 230 nonprofits.8 In a report prepared by the Management Assistance Group for the Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer Foundation,9 several models of back office and group purchase services nonprofits were examined—with for-profit, nonprofit, co-op, and even private foundation providers—but nothing distinctly unique or beneficial attributable to one business model or another was discernable.

In December of 2013, the VSJF Flexible Capital Fund, based in Montpelier, Vermont, received the U.S. Department of Treasury’s approval to be a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI). It is one of 210 L3Cs organized in Vermont, according to interSector Partners. This L3C was created by the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund as a business lending program focused on “royalty financing for growth stage businesses,” emphasizing investments in the “value-added agricultural, forest products, and clean technology sectors.”10 The president of the Flex Fund, Janice St. Onge, is the deputy director of the Jobs Fund, which was created by the Vermont state legislature in 1995 to promote Vermont’s green economy.

Unlike the typical operation of venture capital firms that offer companies equity financing in exchange for some portion of ownership, royalty financing is the provision of equity-like capital financing in exchange for a designated guarantee of a percentage of the business’s overall or product-specific revenues without the company’s giving up a stake in its ownership. Because of this focus on revenues from a product or an array of products, the Flex Fund targets “growth-stage businesses” that offer products that have a potentially high return, rather than potentially precarious start-ups. The Flex Fund website lists six investments it has made in firms engaged in forest products, specialty foods, and renewable energy.11 While sustainability and environmental issues seem to dominate the Flex Fund’s investment portfolio, it is a little difficult to imagine that the Liz Lovely cookie company, Vermont Butcher Block & Board Company, and Vermont Smoke and Cure are the tools of an L3C socialist conspiracy, as conjured by some opponents in North Carolina.

As with The Mission Center’s back office incubator for nonprofits, the royalty financing model of Flex Fund isn’t unique to L3Cs. A number of for-profit firms specializing in royalty financing have arisen in recent years, such as Arctaris Capital Partners LP, in Waltham, Massachusetts, Cypress Growth Capital LLC, in Dallas, and Revenue Loan LLC, in Seattle. And as a certified CDFI, the Flex Fund isn’t alone in Vermont—it joins a CDFI community that includes the Vermont Community Loan Fund, the Northern Community Investment Corporation, Community Capital of Vermont, the Opportunities Credit Union, and Rutland West Neighborhood Housing Services—all 501(c)(3) public charities, except for the credit union, which is a 501(c)(14).

Following L3C Activities: Oversight and Accountability

For anyone interested in the financing of 501(c)(3) public charities—or any other 501(c) tax-exempt entities for that matter—it is possible to examine their Form 990 filings with the federal government, accessible on the GuideStar website (among several others).12 Limited as the 990 may be, it is a multipage document with some breakdown of the entities’ general categories of income and expenditures. Nothing like that exists for L3Cs—or at least nothing that is easily accessible to the public. An investigation of the reports filed by L3Cs in some of the states that have authorized them reveals painfully thin applications and even thinner—boilerplate—updates.

Whether state-authorized L3Cs or benefit corporations, the creation of these “hybrid” entities has not been accompanied by much of a structure for reporting, monitoring, and oversight. The legislation is at best imprecise as regards to what is meant by “limited profit.” How would a state monitor whether the substance of an L3C’s activities are in pursuit of charitable purposes, given that the charitable probity of even some 501(c)(3)s has been suspect? Moreover, the IRS has been quite expansive re its willingness to accept a broad variety of activities as charitable. What a state might hang its hat on with respect to regulatory oversight (vis-à-vis achievement of social benefits) of these entities expressly designed to attract for-profits into the arena of charity is difficult to say. It is fair to say that, despite the endeavors and achievements of the Flex Fund in Vermont, The Mission Center in St. Louis, and others, there hasn’t been enough activity in these nascent corporate models to warrant significant concern about the regulation of L3Cs; there has been little of substance to regulate. Nonetheless, it is difficult to argue with Elizabeth Grant, the attorney-in-charge of the Charitable Activities Section of the Oregon Attorney General’s office, when she observed that the “benefit corporation legislation eliminates the traditional fiduciary obligation to maximize profits, but it fails to provide any enforceable standard to guide the enterprise’s pursuit of social benefits.”13

Finally, the first principle of accountability is disclosure, but disclosure is only effective when the governmental office in charge of oversight and accountability requires the revelation of pertinent information—and then does appropriate oversight of what is actually disclosed. Disclosure is only as good as what is asked for. Below are some examples of the state oversight of L3Cs that demonstrate the limitations of what states have been and may currently be requiring of these hybrid organizations.

Reporting and Disclosure

In North Carolina, the latest list of active L3Cs appears to show ninety-nine.14 For the entities that are active, nearly all their filings—even those with corporate existences in 2010, 2011, and 2012, giving them some time to be active and report—simply have on record in the state’s online database their L3C articles of incorporation, all nearly identical. For instance, the tripartite securities company Melana Development 1, Melana Development 2, and Melana Development 3 filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, but there is nothing about any of Melana Developments’ investment-generating efforts on the state’s web page—only boilerplate text, such as the following for Melana Development 1:15

Persuant [sic] to §57C-2-20 of the North Carolina General Statutes, the undersigned hereby submits these Articles of Organization for the purpose of forming a low-profit limited liability company.

- The name of the low-profit limited liability company is Melana Development 1, L3C (the “Company”).

- The Company shall have perpetual duration.

- The name and address of the individual executing these Articles of Organization is:

Name and Address

Keith Brown, 232 W. Winmore Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27514

Capacity

Organizer - The street address, which is also the mailing address, and county of the Company’s initial registered office are 232 W. Winmore, Chapel Hill, Orange County, North Carolina 27514.

- The name of the initial registered agent is Keith Brown.

- The street address, which is also the mailing address, and county of the Company’s principal office are 232 W. Winmore, Chapel Hill, Orange County, North Carolina 27514.

- The Company is manager-managed. Except as provided by §57C-3-20(a) of the North Carolina General Statutes, the members of the Company shall not be managers by virtue of their status as members.

- This Company is formed for both a business purpose and a charitable purpose that requires operation of the Company in accordance with the requirements of §57C-2-01(d) of the North Carolina General Statutes.

- These Articles of Organization will be effective upon filing.

Follow-up annual reports, which are exceptionally rare, merely restate or modify the organizational structure, management, and registered agent. Nowhere do they detail what the authorized L3Cs are doing, and how.

North Carolina is perhaps a weak example, given the state’s decision in 2013 to reverse its L3C course, but other states do not seem to have developed a significantly different reporting and disclosure regime—at least not one that is easily accessible. And the publicly accessible reporting by L3Cs differs little in other states. For example, on the website of the Secretary of State in Illinois, the public can search for the following information about L3Cs (and, for that matter, LLCs):16

File Detail Report

- The File Detail Report on a corporation or limited liability company includes the most commonly requested information on the business entity (i.e. exact name, date of formation/registration in Illinois, jurisdiction, duration, name of the registered agent and address of the registered office).

- The report on a corporation also includes the names and addresses of the president and secretary.

- The report on a limited liability company indicates whether the company is member managed or manager managed.

- The report provides the last date an Annual Report was filed, indicating whether the company is in good standing.

And the web page of Wyoming’s Secretary of State lists sixty-five L3Cs (although it appears that some twenty-eight have been dissolved as inactive);17 but, as with the other L3C states, there is limited descriptive information of the address and organizer associated with each L3C and in the online information from annual reports, changes in addresses, and registered agents.

An argument could be made that with the first L3Cs created only as far back as 2009, there has been less than sufficient time for many to be active enough to have information worth revealing in annual reports. But for firms that are now four or five years old, and which may have had other kinds of corporate existences—nonprofit or for-profit—before restructuring themselves as L3Cs, this argument doesn’t apply.

So what else, besides lax regulations and oversight, do L3Cs such as TMC, the Flex Fund, and Melana Development get from their L3C structure that they wouldn’t be able to get as 501(c)(3) public charities? Precluded from legally soliciting donations that qualify for charitable deductions, the benefits from the L3C status may boil down to two: one inchoate (branding), and one expectant (superior access to foundation program-related investments [PRIs])—both far more consequential than a difference in filing paperwork.

L3C as Brand Identity: Game on Law, Civic Staffing, and Cross Movement Social Justice Consulting

In Wilmington, North Carolina, “virtual lawyer” Stephanie Kimbro has launched Game on Law, an L3C that, she explains, uses computer games to educate players about their legal rights. “The idea is that they don’t really know they’re playing an estate-planning game,” Kimbro said. “But they see the consequences because they see that they didn’t do what they should have with their will.”18 Commercial entities may sponsor different levels of the game and offer prizes to players who conquer those levels, such as a free mini-counseling session with an estate lawyer, or will documents from RocketLawyer. The charitable purpose may seem a little sparse, but there is, as noted earlier, wide latitude in charitable definitions.

On the Civic Staffing webpage, the firm’s identity as an Illinois-chartered L3C is not immediately evident.19 The company fulfills “light industrial temporary staffing needs” for employers in the Chicago metropolitan area. Its charitable mission is conveyed by its taking referrals for employment from members of its “Civic Partner Network,” nonprofits engaged in workforce development programs funded by the United Way and local foundations. The diverse members of the network include well-respected nonprofits such as Catholic Charities, Centers for New Horizons, Easter Seals, the Lawndale Christian Development Corporation, Mercy Supportive Housing, and Oxford House. The Civic Staffing website distinguishes itself from other job-placement entities with a statement addressing employers about social responsibility, and highlighting three aspects: the referrals from the Civic Partner Network’s nonprofit members; Civic Staffing’s embrace of the principles of ISO 26000—a standardized guide for corporate social responsibility;20 and media recognition accruing to the employers for participating in a socially responsible venture. Needless to say, light industrial temporary staffing is a widely practiced business line for firms such as Kelly Services, which, like many corporate entities, posts a corporate social responsibility statement.21

In Ann Arbor, Michigan, Cross Movement Social Justice Consulting is an L3C formed by Rosemary Linares—a 2010 graduate of New York University’s Wagner School of Public Service—that provides consulting assistance in strategic planning, capacity building, movement building, and intersectional organizational development focused on “identity-based oppressions, including racism, classism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ageism, and ableism.”22 Linares explains on the company’s website that “an L3C is run like a business and is profitable, but its primary aim is to provide a social benefit—through a double or triple bottom line.”23 But if, in Linares’ sentence, “nonprofit” were substituted for “L3C,” for many groups the idea would still be correct, as social benefit is a primary purpose for nonprofits also, and nonprofits have no intention of operating in the red.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

It isn’t as if these L3Cs are cleaning up in terms of returns for the owner-operators. Although L3C legislation doesn’t typically specify what constitutes low profit, on an Americans for Community Development chart comparing L3Cs with LLCs and nonprofits, Lang posits a “return on investment” of between 0 and 5 percent.24 (Our guess is that for most L3Cs the numbers would tend to fall to the lower end of that range.)25 Rather, it is a matter of signaling—identifying L3Cs as a brand that is subtly superior to nonprofits and, perhaps less subtly, for-profits: compared to for-profits, the L3C appears structured to be socially responsible in a world where consumers are increasingly attracted to corporate social responsibility (CSR).

And that is a strong marketing signal. The authoritative Cone Communications global study on corporate social responsibility in 2013 indicated that 93 percent of the public want to see more of their products support CSR, 87 percent consider CSR when deciding what to buy and where to shop, 85 percent make CSR a factor in recommending products and services to others, and 93 percent are more loyal to companies with programs that support social or environmental issues.26

But social responsibility is not the only signal L3Cs are broadcasting. The Americans for Community Development chart compares the 0 to 5 percent ROI for L3Cs with “0 to negative 100%” for nonprofits, suggesting that nonprofits cannot generate a surplus. (They can, of course, but any surplus would be reinvested in the organization rather than distributed to owner-investors.) In the column headed “private sector resources,” L3Cs are linked to the following statement: “Philanthropic source invests with a lower than market rate of return; philanthropic investment lowers the risk and raises potential ROI for subsequent investors.” Nonprofits get a private sector resource description: “Market incentives inadequate or non-existent.”27 The brand implication is that L3Cs are superior to nonprofits in their ability to function and generate a return on investment because, unlike the image of nonprofits, L3Cs are tuned into and responsive to the market.

In 2009, Laura Otten, director of the Nonprofit Center at LaSalle University’s School of Business, responded to the Americans for Community Development chart, writing, “you see the sl[e]ight of hand these self-promoters have used to create this new organization that will compete with nonprofits. Too bad they, as so many others do, like to spin things on an ignorant public, preferring sl[e]ight of hand to truth [. . .]” she added. “Too bad that these self-promoters didn’t understand, as so many people don’t, what a nonprofit is and how it operates. If they had, they would have understood that there is no need for L3Cs, as nonprofits already are a better model for achieving the same ends.”28

Otten is picking up on the marketing and positioning of L3C adherents who signal that their model is superior to nonprofits. For example, in a case study of Maine’s Own Organic Milk Company (MOOMilk) L3C, two authors wrote about the options for setting MOOMilk up to buy and market organic milk from ten northeast Maine dairy farmers. After dismissing profit maximization as a reasonable option for these small dairy farmers, the two wrote, without any specific explanation, “For Maine’s economy, a low-profit firm was clearly superior to nonprofits.”29 For most observers, the dairy farmers seem perfectly suited to be a producers’ cooperative—and may actually be—but the MOOMilk L3C structure serves a marketing and promotion function.

For many, “for-profit” is, inherently, definitionally better than all other alternatives. They have a belief in privatization in education and many other arenas, and view “nonprofit” and “public” as somehow lesser. Wise Philanthropy coprincipal Richard Marker tells the story of the founder of a largely self-funded, failed arts nonprofit who became attracted by the L3C model. “He was enticed by the L3C model because, at least as he read it, more foundations and investors would be willing to put in substantial money, he would have an ownership stake, and, as he imagined, he would be able to fulfill his dream and make money at the same time,” Marker wrote. “[W]hat struck me was that there was nothing about his description which suggested to me that there was a viable business model. If no one would contribute or grant to it when it was a nonprofit, why would they invest in it as a for-profit?”30

The implicit bias is that for-profit status/ownership is somehow inherently superior to the nonprofit form; that the (purported) discipline of the market makes these charitable for-profits somehow stronger and smarter than nonprofits; and that, in contrast to the for-profit, the nonprofit form almost always leads to subpar investment and business decisions (thus the theory that a nonprofit ROI of zero is as good as it gets for public charities). Nonprofit executives, who don’t take a portion of the organization’s net earnings (prohibited under rules against private inurement in public charities), are viewed as somehow less committed and motivated than for-profit executives, who take profit-based compensation. Advocates of L3Cs conjecture that nonprofits lack the discipline of competition in the market, overlooking the constant competition in the nonprofit sector for contracts and “market” position, and for access to quality staffing and leadership.

The following proposal, put forward by Cause Capitalism blogger Olivia Khalili, sums it up: “Businesses are held financially accountable by the market[. . . .] Why not also look at creating superior nonprofits by applying specific market mechanisms?”31 By investing in an L3C, in other words, one is getting a superior brand of nonprofit entity—an assumption that, to date, is not empirically verifiable. It may be that the very limited results of L3Cs are attributable to their short life spans thus far; but, if they are unable to show substantive achievement in future, they will become the newest—but certainly not the last—example of the emperor’s new clothes.

L3Cs Following the Money: Private Investment and PRIs

Marketing a brand leads a business to sources of investment. Where might the nation’s L3Cs find capital to advance their programs, which are ostensibly geared toward a core commitment to achieving charitable missions? The answer lies in private investment and PRIs.

Private Investment

Presumably, the for-profit structure affords L3Cs—and other hybrid entities—access to forms of capital and, more generally, to the capital markets in a manner that is superior to what nonprofits might be able to raise. But Richard Steinberg, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis professor of economics, philanthropic studies, and public affairs, wrote in a 2012 review of hybrids that “LLCs (Limited Liability Companies), L3Cs (Low-profit Limited Liability Companies), CICs (Community Investment Corporations), B corporations, Benefit corporations, and Social Impact Bonds lose the efficiency advantage of traditional for-profits and do not enhance access to capital over the nonprofit form.”32 So which is correct? The problem with Steinberg’s and comparable visions of L3Cs’ financial access is that they are rarely if ever based on more than an example or two—if any—of the financing going to and through actual L3Cs.

As few of the functioning L3Cs seem to be active enough to warrant much regulation, there are few that have much public evidence of capital flows going to their business activities. But examples do exist—some of which tap the new world of crowdfunding that has captured the imagination of nonprofits and individuals alike. Kimbro plans to raise money for her Game on Law L3C by launching crowdfunding campaigns on Kickstarter or Indiegogo. In South Carolina, the founders of Rock Hill Yoga hope to establish themselves as an L3C, and have launched a crowdfunding campaign on Indiegogo. Jennifer Lapidus appears to have launched her Common Ground L3C mill with a successful $18,000 Kickstarter campaign.

Not all L3C crowdfunding campaigns are successful. The Indiegogo campaign of Detroit EM News L3C to raise $10,000 for a 2012 Halloween masquerade event, for example, ended up with no funds raised at all. Whether $45,000 for a yoga studio or $18,000 for a wheat mill, these are small-scale fundraising operations that are probably little different from those of the tiny nonprofits that charitable entrepreneurs initiate every year.

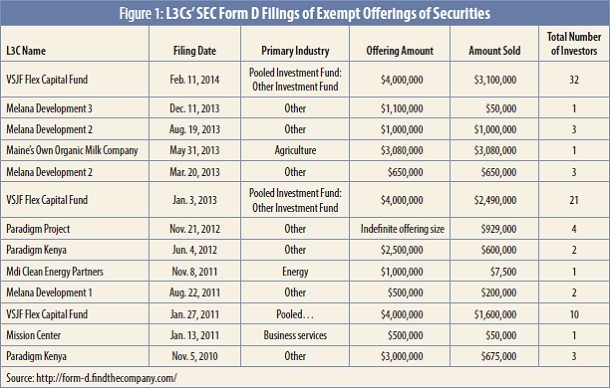

But while for-profit firms may have access to capital markets for equity financing of a little more size and substance than crowdfunding campaigns generally bring, it does not appear that more than a half dozen or so L3C efforts to raise more-substantial equity investment have been filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The most successful of these efforts appears to have been MOOMilk L3C, which raised over $3 million in an offering in May 2013.33 MOOMilk is noteworthy in that it raised exactly what it had sought; but for the handful of others that have gone to the equity markets the results have been smaller, as seen in figure 1 (below)—though the Flex Fund, as a state-created CDFI, has raised significant equity investment. The list indicates only a small proportion of the field of authorized L3Cs making headway in raising equity financing. And could they have done just as well if they had not been L3Cs? The Flex Fund is a CDFI structured as an L3C, but it is only one of the more than 950 nonprofit and for-profit CDFIs certified by the U.S. Department of Treasury that have raised comparable or much higher investment amounts from a variety of investors.34 It doesn’t appear that the bulk of CDFIs have been constrained by their lack of an L3C structure; nor is the Flex Fund particularly advantaged.

In addition to the small movement into equity financing sources, some of the other models of L3C capitalization look to be as informal as crowdsourcing or crowdfunding. For example, ReCitizen, headquartered in Washington, DC, but registered as an L3C in Vermont, provides “web tools to advance citizen-led regeneration of communities and natural resources”—tools including crowdmapping, crowdsourcing, and crowdfunding.35 It raises money by charging $1,450 for two-day training programs to become a Certified Urban/Rural/Environmental Revitalization Specialist, and charging membership fees for—and taking a cut of the proceeds from—the use of its crowdsourcing tools. There is nothing especially L3C-dependent in that business model, though one might question whether a two-day training to be a “CURER” accomplishes much for the people who pay for the training.

PRIs

Nonprofits in need of financing might be looking for charitable donations or foundation grants for their activities, and PRIs, being debt or equity investments by foundations in furtherance of their charitable purposes, would fit that bill. L3Cs, on the other hand, not being 501(c)(3) public charities, typically would not be soliciting or receiving money as such. However, in news reports, either the press or some of the L3Cs themselves appear confused about L3C access to foundation grant support. For example, the normally reliable Chicago Tribune described former Chicago Mayor Richard Daley’s new L3C (The Sustainability Exchange), established to advise other cities on making infrastructure retrofits and upgrades, as similar to an LLC—except that it might have easier access to investments from “grant-making nonprofits.”36 And an article in the Bangor Daily News indicated that MOOMilk’s L3C status would “open the door to funding from foundations and endowment.”37

An L3C called SEEDR may be the exception to the rule. The Atlanta-based international R&D entity has been the recipient of two large grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation,38 including one in 2009, described as a grant of $539,566“to develop a new line of insulated containers for transporting and storing vaccines and other medicines in developing countries.”39 The grant looks for all intents and purposes like a program-related investment, however, or perhaps some other form of recoverable grant (if listed and structured as a grant, even if recoverable, it would not count as debt on the recipient organization’s balance sheet). The second Gates grant appears to be more straightforward: $88,700 over a 2.5-year period for the same purpose as the 2009 grant, looking like a supplement to the 2009 investment.

A couple of other L3Cs have scored foundation grants. In 2010, the Ford Foundation awarded a two-year grant of $420,000 to a Michigan-based L3C, Disruptive Innovations for Social Change, to document and replicate a model continuum of job training and job placement services40—a model of “employer resource networks” that, by the way, sounds like the kind of program that might have been developed by any number of expert nonprofits in the job training and job placement field.41 The Kresge Foundation followed, in 2011, with a three-year general operating grant of $300,000.42 That same year, Univicity, a California-based entity that was organized as an L3C under Wyoming’s statute, and which uses information technology to improve the effectiveness of humanitarian aid NGOs, received a $1.32 million PRI from the Kay Family Foundation in California, followed by another $250,000 PRI from the Kay foundation in 2011—both to support the development of specialized software. Later, Univicity spun off one of its projects to become a new L3C called Project Bonfire, which then received an $850,000 PRI from Kay.43 But 501(c)(3) charities are meant to be the primary direct recipients of project and operating grants from private philanthropies, and the Ford, Kresge, and Kay grants to L3Cs appear to be anomalies. An L3C looking for foundation grant support might be better off as a public charity, even with the burgeoning “sector-agnostic” interests of some foundation leaders.44

After all is said and done regarding finances, L3C access to foundation PRIs like those of Ford, Kresge, and Kay is the Holy Grail for these hybrids—and, in fact, has from the start been the generative theme behind the creation of L3Cs, regardless of the frills of other kinds of private financing and investment that L3C advocates tout. All of the state L3C legislation is written to match the U.S. Treasury Department’s definitions of PRIs.45 As described on the webpage of the Vermont Secretary of State, “The basic purpose of the L3C is to signal to foundations and donor-directed funds that entities formed under this provision intend to conduct their activities in a way that would qualify as program-related investments.”46 The constraint is that foundations can use debt or equity investments that count toward their required qualified distributions, or “payout,” only if they contribute to the foundations’ charitable purposes.

Some L3C advocates want foundations’ awarding of PRIs to L3Cs to be easier and more automatic. They decry the need, for instance, of the IRS opinion letters that foundations frequently seek as legal cover for making PRIs—presumably seeing them as a reason why foundations do not often make such investments in general, much less PRIs to L3Cs. Indeed, with the support of the Council on Foundations, L3C lobbyists have promoted federal legislation that would make PRIs easier for foundations in general, not only reducing the need for IRS opinion letters but also allowing L3C recipients to voluntarily self-monitor and report on their PRI-funded activities. (In a way, that matches the minimal regulatory functions built into state-authorizing legislation for L3Cs, in which there is little in the way of reporting, and regulation would be largely self-imposed.) There is nothing automatic about PRIs, however, given the need for foundations to be able to underwrite debt or equity investments—a categorically different and more complex task than underwriting foundation grants, and more complex for monitoring as well. The reluctance of many foundations to make PRIs is fundamental: the aforementioned predisposition toward making grants rather than debt or equity investments (which they can make from their endowments as mission-related investments with more flexibility than the strictures of PRIs); discomfort with the notion of underwriting debt and equity (more of a banker’s skill set than a grantmaker’s); and an aversion to assuming the monitoring and reporting requirements involved in fulfilling the expenditure responsibility dimensions of PRIs.

New IRS guidance offers several model examples of private foundations using PRIs for for-profit small businesses, demonstrating that PRIs are not restricted to nonprofit recipients but are still meant to fulfill charitable objectives, not income or profit generation. That this recent IRS guidance on PRIs doesn’t satisfy L3Cs demonstrates what L3Cs want: a much more flexible approach to PRIs, more latitude on the definition of what constitutes charitable purpose, and less IRS regulation of the content and process of how recipients use PRIs.

Going Forward

Many of the people creating L3Cs are well-intentioned individuals who are motivated by the idea of using for-profit business models to achieve socially beneficial goals. But they are pursuing these models relying more on image and branding than substance, on the assumption if not contention that nonprofits are an inferior means of achieving social goals, on a desire to escape even the minimal regulation and oversight of public charities, and on the all-consuming objective of getting access to private foundation program-related investments.

While foundations can and should do more program-related investments, they should be doing even more in the way of grantmaking, which is still their foremost institutional function in the charitable sector. While foundations can and should be making socially beneficial PRIs to a range of potential recipients (including certain for-profit entities), as fitting the IRS instructions, foundations need to remember and reprioritize their commitment to nonprofits as their primary constituency for grants and PRIs. While foundations may use their assets for debt and equity (contributing to their required 5 percent payout), they should be devoting much more attention to using the other 95 percent of their assets for mission-related investments, to push the corporate sector to higher levels of social responsibility.

That being said, L3Cs do not seem to be an improvement on the capacities and functions of public charities. 501(c)(3)s are not precluded from earning revenue, they are not precluded from accessing program-related investments, and they can even partner with for-profit entities to accomplish a wide variety of socially beneficial purposes. The logic that L3Cs are superior to nonprofits because of their for-profit decision-making structures is not supportable. Neither is the notion that business people are somehow more intrinsically accountable and market-oriented than nonprofits. Whatever L3Cs are actually achieving is already well done by the nonprofit sector across the country. There’s nothing new except owners who, in theory, will be able to personally benefit from whatever profits the entities might generate.

Ultimately, the L3Cs lead toward a couple of serious problems for the accomplishment of charitable functions in our society. There are already challenges with transparency and accountability for nonprofits; L3Cs represent a movement backwards in charitable accountability, avoiding the relatively limited transparency measures applicable to nonprofits by choosing the all-but-nonexistent accountability regimen that states apply to L3Cs. Moreover, the L3C model fundamentally angles for access to foundation PRIs. One might argue that foundations should be engaged in more mission-related investment, devoting their investment assets to socially responsible business ventures, but there is no compelling argument for foundations to divert PRIs—which count toward their mandated qualifying distributions/payout—from nonprofits to sui generis for-profit L3Cs. L3Cs are an attractive brand for some potential investment sources, but are they an advance over the 501(c)(3) public charity organizational structure? The evidence over the past few years is unconvincing.

Notes

- Doug Batey, “Rhode Island Becomes the Newest State to Authorize Low-Profit LLCs—What’s Going On Here?,” LLC Law Monitor, September 12, 2011, www.llclawmonitor.com/2011/09/articles/lowprofit-llcs/rhode-island-becomes-the-newest-state-to-authorize-lowprofit-llcs-whats-going-on-here/.

- Anne Field, “North Carolina Officially Abolishes the L3C,” Forbes, January 11, 2014, www.forbes.com/sites/annefield/2014/01/11/north-carolina-officially-abolishes-the-l3c/.

- Laura Leslie, “House Votes Down Benefit Corporations,” May 15, 2013, WRAL.com, www.wral.com/house-votes-down-benefit-corporations/12451435/.

- “L3C Tally,” interSector Partners, L3C, accessed March 26, 2014, www.intersectorl3c.com/l3c_tally.html.

- While the Mission Center operates in downtown St. Louis, Missouri, it is actually one of 217 L3Cs organized and registered in Michigan, according to a February 16, 2014, tally by interSector Partners, L3C (see note 4, above).

- Samantha Liss, “Social Entrepreneurship Incubator Welcomes First Class of Startups,” Tech Flash (blog), St. Louis Business Journal, January 7, 2014, www.bizjournals.com/stlouis/blog/BizNext/2014/01/social-entrepreneurship-incubator.html.

- See www.missioncenterl3c.com/.

- “Mission Statement,” Tides, accessed February 17, 2014, www.tides.org/about/.

- Mark Leach, Outsourcing Back‐Office Services in Small Nonprofits: Pitfalls and Possibilities (Washington, DC: Management Assistance Group, 2009), www.managementassistance.org/ht/d/sp/i/9297/pid/9297.

- “VSJF Announces Launch of New Flexible Capital Fund,” press release, Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund, June 29, 2001, vtdigger.org/2011/06/29/vsjf-flexible-capital-fund/.

- “Portfolio Company Briefs,” Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund, www.vsjf.org/what-we-do/flexible-capital-fund/Portfolio-Company-Briefs.

- See www.guidestar.org/.

- Elizabeth M. Grant, “Hybrid Enterprises and the Application of State Charitable Regulatory Principles as a Guide Toward an Effective Regulatory Framework” (paper presented at the 2013 Columbia Law School Charities Regulation and Oversight Project Policy Conference on the Future of State Charities Regulation: Challenges and Interests of the States in Social Mission/Hybrid Organizations), academiccommons.columbia.edu/catalog/ac%3A168610.

- A search on the North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State website showed 108 corporate records, but only 99 appeared to be L3Cs or apparently L3C-structured LLCs. North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State: Corporations Division, www.secretary.state.nc.us/corporations/searchresults.aspx?onlyactive=ON&Words=ANY&searchstr=L3C, accessed February 17, 2014.

- See document filings for Melana Development 1, L3C (www.secretary.state.nc.us/search/CorpFilings/9805589), Melana Development 2, L3C (www.secretary.state.nc.us/search/CorpFilings/10191187), and Melana Development 3, L3C (www.secretary.state.nc.us/search/CorpFilings/10392281). North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State: Corporation Division, accessed February 18, 2014.

- “Business Services: Corporation/LLC Search/Certificate of Good Standing,” Illinois Secretary of State website, accessed February 17, 2014, www.cyberdriveillinois.com/departments/business_services/corp.html.

- Per filing search on Wyoming Secretary of State website, accessed February 17, 2014, wyobiz.wy.gov/Business/FilingSearch.aspx. Search for L3C as the word in the filing name.

- Amber Nimocks, “Gaming the Estate Process,” North Carolina Lawyers Weekly, July 12, 2013, nclawyersweekly.com/2013/07/12/gaming-the-estate-process/.

- See www.civicstaffing.com/.

- See www.iso.org/iso/home/standards/iso26000.htm.

- “Sustainability,” Kelly Services, accessed February 18, 2014, www.kellyservices.com/Global/About-Us/Corporate-Responsibility/.

- Cross Movement Social Justice Consulting home page, accessed February 18, 2014, cmsjconsulting.com/.

- “What’s an L3C?,” accessed February 17, 2014, cmsjconsulting.com/whats-an-l3c/.

- Per chart provided by Americans for Community Development, posted in “A Tough Hybrid to Swallow,” Laura Otten, PhD, The Nonprofit Center at LaSalle University’s School of Business blog, November 19, 2009, www.lasallenonprofitcenter.org/a-tough-hybrid-to-swallow-the-l3c3/.

- The calculation of profit for owner-organizers of L3Cs is made more difficult by the possibility that the owner-organizer could pay him- or herself a salary as part of the entity’s operating costs, plus a cut of the profits. For example, the California-based Univicity’s charitable funders—the Kay Family Foundation (private foundation), and World Vision (public charity)—hold A shares and decision-making authority on the L3C’s board. The executives of Univicity receive salaries from the firm and hold “B Shares” in lieu of higher salaries, though if the firm is profitable they benefit from their ownership of the shares. Cf. Roxanne Phen, The Future of Philanthropy: Hybrid Social Ventures (Muskegon, MI: Americans for Community Development, 2011).

- “Cone Releases the 2013 Cone Communications/Echo Global CSR Study,” press release, Cone Communications, May 22, 2013, www.conecomm.com/2013-global-csr-study-release.

- Laura Otten, “A Tough Hybrid to Swallow.”

- Ibid.

- Nancy Artz and John Sutherland, “Low-Profit Limited Liability Companies (L3Cs): Competitiveness Implications,” Competition Forum 8, no. 2 (2010).

- Richard Marker, “To L3C or Not to L3C? That Was the Question,” Wise Philanthropy, February 11, 2013, wisephilanthropy.com/to-l3c-or-not-to-l3c-that-was-the-question/1032.

- Olivia Khalili, “It’s Time for an Evolution: Creating the Superior Nonprofit,” Cause Capitalism: Good for Profit, 2011, causecapitalism.com/its-time-for-an-evolution-creating-the-superior-nonprofit/.

- Richard Steinberg, “What Should Social Investors Invest in, and With Whom?,” July 3, 2012, c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.istr.org/resource/resmgr/wp2012/steinberg_social_investment_.pdf.

- Maine’s Own Organic Milk Company, L3C Form D, filed May 31, 2013, FindtheCompany.com, accessed February 17, 2014, form-d.findthecompany.com/l/93280/Maine-S-Own-Organic-Milk-Company-L3c.

- “What Are CDFIs?,” CDFI Coalition of Community Development Financial Institutions, accessed February 18, 2014, www.cdfi.org/about-cdfis/what-are-cdfis/.

- “What is ReCitizen?,” Recitizen.org, accessed February 17, 2014, www.recitizen.org/what-is-ReCitizen.

- Melissa Harris, “Daley, Investment Firm Offer Cities Advice on Cost-Saving Upgrades,” July 5, 2013, Chicago Tribune.

- Erica Quin-Easter, “Mission-Driven: The Path to Nonprofit Entrepreneurship,” Bangor Daily News, March 21, 2013, bangordailynews.com/2013/03/21/businessmission-driven-the-path-to-nonprofit-entrepreneurship/.

- “SEEDR,” Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, www.gatesfoundation.org/How-We-Work/Quick-Links/Grants-Database/Grants/2009/10/OPP1004459.

- Dave Williams, “New Business Model Touted as Economic Boost,” Atlanta Business Chronicle, April 1, 2011, www.bizjournals.com/atlanta/print-edition/2011/04/01/new-business-model-touted-as-economic.html.

- Disruptive Innovations for Social Change L3C, Grants Database, Ford Foundation, accessed February 17, 2014, www.fordfoundation.org/grants/grantdetails?grantid=113183.

- See Bridget Timmeney and Kevin Hollenbeck, Employer Resource Networks: What Works in Forming a Successful ERN? (Grand Rapids, MI: Disruptive Innovations for Social Change, with W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research and The Ford Foundation, 2012).

- Disruptive Innovations for Social Change L3C, Grant Highlights, The Kresge Foundation, accessed February 17, 2014, kresge.org/grants-social-investments/grants/disruptive-innovations-for-social-change.

- Phen, The Future of Philanthropy, 28–29.

- “Nonprofits and Philanthropy: Scenario II—An Interview with Ralph Smith,” the Nonprofit Quarterly, 15, no. 4 (Winter 2008), 38–42.

- Dana Thompson, “L3Cs: An Innovative Choice for Urban Entrepreneurs and Urban Revitalization,” American University Business Law Review 2, no. 1 (2012): 146, digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=aublr.

- “Low-Profit Limited Liability Company,” Vermont Secretary of State: Corporations Division, accessed February 17, 2014, www.sec.state.vt.us/corps/dobiz/llc/llc_l3c.htm.

Rick Cohen is the Nonprofit Quarterly’s correspondent at large.