Editors’ note: This article is from NPQ’s new, spring 2015 edition, “Inequality’s Tipping Point and the Pivotal Role of Nonprofits.”

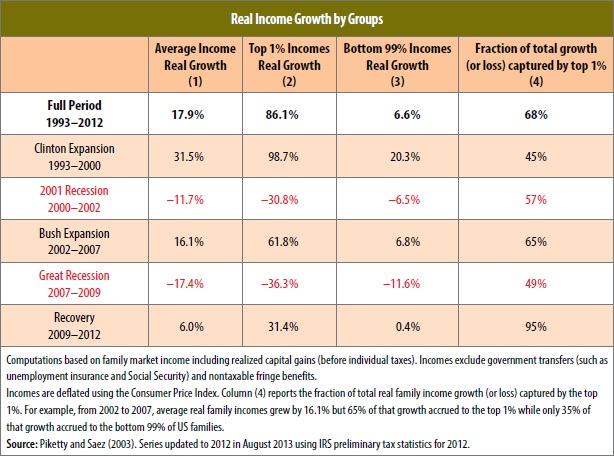

The one characteristic that sets the current postrecession recovery apart from others in this nation’s history is the overwhelming proportion of the recovery proceeds that have gone to the top 1 percent of asset holders. The table below, originally printed in the Washington Post’s WonkBlog in 2013, provides a stark picture of just how marked this distinction has been.1

This article looks at the possibility that this inequality in the sharing of recovery proceeds is reflected in philanthropy.

The Giving Recovery as a Mirror of the Larger Recovery

Too many large donations disproportionately serve the personal interests and values of the benefactors, says Patrick Rooney, associate dean for academic affairs and research at the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, and author of Giving USA’s annual report. Additionally, according to Rooney, the increases in individual giving last year were due primarily to a proliferation of “mega-gifts” of $80 million or more, and “the gains and losses in giving are increasingly driven by a smaller percentage of the population.”2

Rob Reich, associate professor of political science at Stanford University, takes it a little further: “The favored charities of the wealthy are gaining in share in the philanthropic economy. The total amount of money given away by the very wealthy is going up, not because they’re giving away a greater share of their income [but because] their total income and wealth itself has grown.”3 According to Reich, the nation’s postrecession economic gains have largely been concentrated in the top income tiers, and these donors tend to give to higher education, medical research, and cultural institutions rather than to, say, day-care centers or community health centers in poor neighborhoods. As we will see later, however, problems do exist as well when high-wealth donors insert themselves into problem solving for low-income neighborhoods—sometimes referred to as “committing philanthropy.”

As Rooney explained in an interview with the Nonprofit Quarterly, in calculating the 2014 findings of Giving USA, any gift of $80 million dollars or above was considered a mega-gift because gifts this size were large enough in 2013 to affect the rate of change in total giving. These are added to the numbers after general forecasting is done. This year, gifts in that category totaled $4.22 billion, in contrast to last year, when they were a mere $1.55 billion. That is an increase of 172 percent in mega-gifts. (As a side note, the largest proportion of mega-gifts in 2013 was relatively new money, with $3 billion being contributed by living donors and the rest contributed through bequests.)

The ten largest donations in 2014 equaled $3.3 billion, with one of those a bequest of $1 billion from Detroit businessman Ralph Wilson Jr. to his own foundation. That $3.3 billion contributed by ten sources constitutes 1 percent of all donations for 2014 in the United States.

Does that mean that these folk are just extraordinarily generous? It may be worth noting here that wealthy people are not more generous than other Americans. In fact, the opposite is true: poor people give far more a proportion of their incomes than do the rich; but the astronomical numbers on large charitable gifts from high-dollar donors are nothing less than staggering.

Gifts Often Stay Close to Home: Geographic and Institutional Inequities

In 2013, Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan, both under thirty years old, gave stocks worth $1 billion to the Silicon Valley Community Foundation—the same foundation that was graced with a $500 million donation from GoPro founder Nick Woodman in 2014. This reinforces the fact that because many larger gifts are given locally, geography over need can be a deciding factor in the final destination of contributions. A study by the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy found that, between 2000 and 2011, half of all gifts of a million dollars or more given by donors between 2000 and 2011 went to a recipient in the state where the donor lives—and 60 percent were given in the same region. These gifts also tend to go to a limited number of institutional types, with 36 percent of all dollars given in million-dollar gifts over the ten years between 2000 and 2011 going to foundations, and 32 percent going to higher educational institutions.4 This is more than two-thirds of all million-dollar-plus gifts.

Waves of Record-Setting Mega-Gifts to Already-Rich Institutions

Gifts to universities and university-related organizations are setting records—the Broad Institute in Cambridge received $650 million in 2014 from billionaire Ted Stanley to support work in identifying the genetic roots of schizophrenia within what will be called the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research. The Broad Institute, which partners with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University, was established as a collaborative biomedical research center. This followed two major founding gifts of $200 million and $400 million from Edythe and Eli Broad.

In September 2014, Harvard received an institutional record-setting gift of $350 million from the Morningside Foundation to help support Harvard’s School of Public Health. The foundation is associated with private-equity-and-venture-capital firm Morningside Group, which is ran by the descendants of T. H. Chan, founder of one of the largest real estate turns in Hong Kong in the 1960s. One of these descendants, Gerald Chan, attended Harvard’s School of Public Health in the 1970s. And Yale, too, received a record-setting gift—$250 million, from a 1954 alumnus, Charles B. Johnson. That money will be used to break ground on two new buildings.

Thus, the endowments of universities and colleges are climbing even as the cost of education climbs for students and as young people are entering their lives with increasingly overwhelming debt. This does not constitute any kind of redistribution.

Two other examples of close-to-home giving in 2014 were from John and Laura Arnold, whose $300 million gifts went mostly to their family foundation—money that will be regranted over time—and from Pierre and Pam Omidyar, who gave $230 million in total that year, of which $225 million went to the health-related organization founded by Pam Omidyar, known as HopeLab.

Barriers to Redistribution: Nothing New Here, Folks…

Maybe giving to elite universities is a problem, but what could possibly be the problem with giving to foundations that presumably will regrant the money—sometimes to good causes? In “Philanthropy and Inequality: What’s the Relationship?,” Kevin Lakowski describes the barriers that are set up to any redistributive purpose:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

There is increased emphasis on financial intermediaries. For nearly five decades, charitable giving as a share of GDP has remained around 2 percent. Charitable giving has not increased from this vantage; it has instead shifted. In 1978, foundations received 4 percent of charitable dollars; by 2010, foundations were receiving 11 percent of charitable dollars. In effect, the rise of philanthropy means that less is going “directly” to charity as a share of GDP, and more is moving to a larger and larger set of competing financial intermediaries.5

Philanthropy does not generally act as an effective method of redistribution in a democracy. Rich people tend to give to rich institutions; they do not generally endow housing for poor people with grants in the multiple millions.

…But All This May Increasingly Threaten Democracy

Deductions for charitable giving are taken primarily by the top 20 percent of wealth holders; this money amounts to somewhere close to an astounding $40 billion a year.6 In other words, this is a $40 billion tax expenditure that takes decision making out of the hands of elected representatives (who are, at least in theory, accountable to the public) and into the hands of the rich—who are not accountable to the public but who nonetheless, as generous philanthropic citizens, are infused with the soft golden light of public goodness.

Oligarchy Unlimited

It is, of course, well known that people of wealth tend to give to institutions that have played some role in their own lives. Thus, people may give to universities they have gone to, prep schools they would like their child to attend, a hospital that has served a family member well. They do not attend the local food bank, and as society becomes more wealth polarized, some worry that people of wealth will become less and less likely to respect the intelligence and voices of people at lower-income strata or to empathize with their struggles.

But even when a billionaire does involve him- or herself with an issue that is aimed at addressing a social reality that affects the lives of people at those lower strata, if their approach is top down it can cause serious harm to communities. Examples of this kind of high-handed strategy are legion, with a lengthy historical tail.

The double whammy of taking deductions, which reduces this country’s tax base, while contributing individually to causes (not to mention political campaigns) gives billionaires outsize public influence—the very definition of oligarchy. Robert B. Reich, public policy professor at University of California-Berkeley and former labor secretary (no connection to Rob Reich at Stanford) comments:

“We’re back in the late 19th century when the robber barons lorded over the economy and almost everyone else lost ground. The Vanderbilts, Carnegies, Rockefellers made so much money that they too could give away large chunks to charity and still maintain their outsize fortunes and their power and influence.”7

As wealth has become more stratified, giving goes up, but more of it is being directed by the highest-level givers. This trend is, therefore, capable of undermining democracy by giving high-level givers a defining voice in social issues—at least temporarily, until people rebel, something that they will likely have to do without a multi-million-dollar grant.

Notes

1. Dylan Matthews, “How the 1 percent Won the Recovery, in One Table,” WonkBlog, Washington Post, September 11, 2013.

2. Nina Glinski, “Causes Favored by U.S. Elites See Good Holiday Tithings: Economy,” Washington Post with Bloomberg, December 16, 2014.

3. Ibid.

4. Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, A Decade of Million-Dollar Gifts: A Closer Look at Major Gifts by Type of Recipient Organization, 2000–2011 (Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, 2013), 5,12.

5. Kevin Laskowski, “Philanthropy and Inequality: What’s the Relationship?,” Responsive Philanthropy (Winter 2011/2012): 7.

6. Tax Policy Center; TaxVox; “How to Cut the Charitable Deduction without Reducing Giving,” blog entry by Howard Gleckman, December 5, 2012.

7. Heather Horn, “The Backlash Against the Billionaires’ Pledge,” The Wire: News from The Atlantic, August 6, 2010.