July 15, 2015; Slate

Southern Virginia University has advertised for “volunteer professors.” Southern Virginia is a tiny school with an enrollment of around 800, located in the Shenandoah Mountains. Over 90 percent of its students are Mormons (over one-fifth returned missionaries), though the school is not officially a part of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Southern Virginia’s tiny endowment—$894,000—puts it at the bottom of the 851 U.S. and Canadian colleges and universities ranked by the National Association of College and University Business Officers and the Commonfund Institute. Maybe that explains why the university felt the need to look for volunteer teachers.

Reactions to the ad, as recounted by Rebecca Schuman for Slate, revealed how many young academics, studying for or holding Ph.D. degrees, see their careers as having to function as volunteers or quasi-volunteers in the university setting. As Slate’s education columnist, Schuman had previously written that “assistant adjunct” was the academic world’s worst job title, but “volunteer professor” might beat that.

Schuman points out that Southern Virginia does offer its volunteer professors “complimentary apartment-style housing and five meals a week,” but that’s the sum total of the fungible financial benefit the volunteers would get. While dismayed, many readers told Schuman that they weren’t surprised, and one actually said “she’d consider applying, just for the affiliation and library privileges.” She writes that there is a “vast ‘oversupply’ of Ph.Ds. cramming into near-voluntary part-time work, for which they are supposed to genuflect silently in thanks.”

SVU informed Schuman that the ad hadn’t been meant for wide circulation. Rather, it was aimed at Mormon retirees, for whom teaching at a Mormon school would be something like a new mission in the church. A school spokesman said that the volunteer professor role was “‘grounded in the long-standing Latter-day Saint tradition’ of volunteerism.” Though intended for older LDS retirees, the volunteer professor ad resonated with many in the academic world who are used to looking for adjunct positions that pay next to nothing or, in this case, a volunteer position that would provide housing and occasional meals.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

For Schuman, the issue is the value that society accords to holders of Ph.Ds.—and to some extent the value that universities themselves do, where Ph.Ds. are expected to work more for the intellectual achievement than the expectation of decent compensation. “There has to be some sort of Golden Mean,” Schuman writes, “where professors can admit to a passion for research and teaching that does often transcend how many people feel about their day jobs, but that also acknowledges that being a professor is still a job, still requires labor, still adds value to the university, still deserves the dignity of an honest day’s pay for a hard day’s work.”

But that is only part of the problem. It’s not just how academics view themselves; it’s how universities—not just tiny, undercapitalized ones like Southern Virginia but big wealthy schools with endowments in the billions—rely on the labor of adjuncts and teaching assistants whom they pay meagerly. Organizing efforts for better pay for adjuncts and TAs have been emerging in recent years, notably Adjunct Action, sponsored by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which recently called for a $15,000 per course minimum compensation. Adjunct Action has succeeded in organizing part-time faculty at Tufts University, who will make a minimum of $7,300 per course by September 2016. Another group called New Faculty Majority, with foundation expert and Chronicle of Philanthropy columnist Pablo Eisenberg, listed on its advisory board works on improvements in a variety of issues facing part-time or contingent faculty beyond compensation, including job security, academic freedom, the right to participate in faculty governance, benefits, and unemployment insurance. Another organization, the Coalition of Contingent Academic Labor, whose mission appears similar to the New Faculty Majority, boasts an international advisory committee with a number of members affiliated with the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and the American Association of University Professors (AAUP).

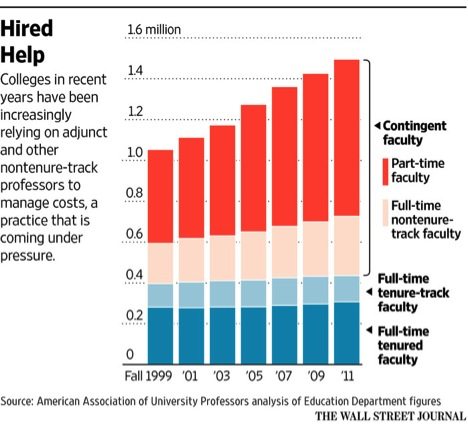

Eisenberg has written about the “dehumanizing” aspects of the adjunct teaching experience, including just-in-time hiring that leaves adjuncts little or no time to prepare for their courses, limited adjunct access to technology and other resources (including office space) provided for regular faculty, and the adjuncts’ sacrifice of time and money to enhance the students’ experiences without acknowledgement. Universities rely more and more on part-time adjunct or contingent professor labor, as this chart from the Wall Street Journal shows:

Part-time adjunct faculty, contingent faculty, and non-tenure track faculty are increasingly getting organized; non-tenure track faculty at Tufts and adjuncts at Boston University among other schools have voted to unionize. The obstacle they face, however, is the expectation that workers will work not in full-time permanent jobs, but in part-time temporary positions with few guarantees of decent wages, benefits, or employment protections. The use of part-time contract employees like the drivers working for Uber and Lyft is another manifestation of the larger societal phenomenon that is the “casualization” of the labor force.

Nonprofits, whether as employers or as advocates of volunteerism, run the risk of using minimally compensated or stipended volunteers to further casualize the treatment of their workers. In universities, this has become the norm, as the public and administrators think part-time faculty teach for the “fun” of teaching, notwithstanding the measly pay and inadequate support. Maybe tiny Southern Virginia University can’t afford it, but those schools with billion-dollar endowments can and should provide adjuncts and other part-time teachers with better wages and working conditions.—Rick Cohen

Disclosure: This author has been an adjunct professor at St. Peter’s College, Rutgers University, and Columbia University, and doesn’t recall being paid more than a couple of thousand dollars per course and was never provided with office space or library privileges.