November 18, 2015; Hyperallergic and TechCrunch

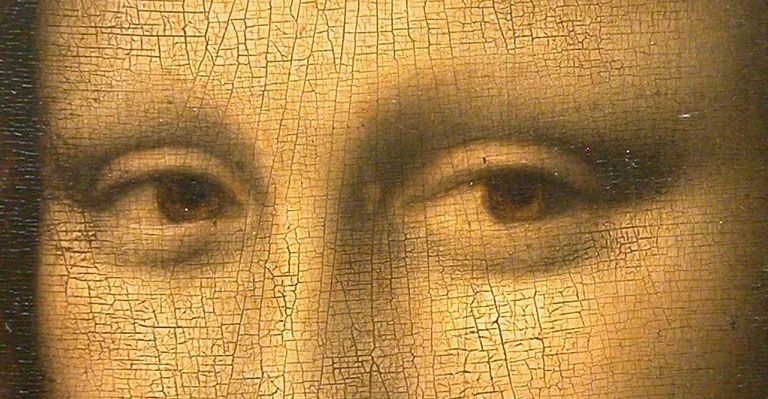

The Mona Lisa is among the most famous paintings in the world—revered for centuries, owned by emperors and kings, and visited in the Louvre by approximately 6 million people annually. Still, its beauty and impact are diminished for people who cannot see it because of visual impairment. But that may be about to change if either of two crowdfunding campaigns currently on Indiegogo and Kickstarter succeeds.

The one on Indiegogo is a campaign proposed by Unseen Art that’s “raising $30,000 to create a software platform that would allow those without sight to download famous artworks and 3D-print them.”

Founder Marc Dillon has said, “The classical artworks of the world are something we believe everybody should have accessibility to and it should be free. […] So we have to build something in order to do that.”

The notion is to “let artists create 3D interpretations of artworks by scanning a photo of the original, then adding depth and simplifying detail.” Then, anyone with access to a 3D printer could access the file, download, and print.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The project on Kickstarter from the group 3DPhotoWorks is different in that it is looking to fund a much more expensive, commercial platform for use by museums, science centers, and other cultural organizations. They’ve developed and tested “a process called 3D Tactile Fine Art Printing” that is “capable of converting a painting, drawing, photograph or other form of traditional 2D artwork into a 3D printed tactile fine art” as large as five feet by ten feet.

The technology is based on the science of neuroplasticity and inspired by “the work of Dr. Paul Bach-y-Rita, a neuroscientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison,” which shows “that the human brain is capable of processing the tactile information obtained from fingertip contact like it had been obtained from visualization.” In these cases, sensors have been “implemented into the prints, which when touched, give off audio that tells the user what is being shown at that part of the painting.” In that way, their brain can put together a mental picture of what’s in the painting, photograph or drawing.

One aesthetic question raised by this, according to Tech Crunch, is whether “a 3D painting [is] still a painting?” And, in another sense, are the new creations new pieces altogether? Dillon sees this as a differentiation between the two approaches, and describes 3D Tactile Fine Art Printing as “more of a relief style” versus the fully 3D models Unseen Art aims to distribute.” He argues that there’s particular value in the 3D modeling he’s proposing because they found, “there needs to be some depth of touch, and there needs to be some limitation to detail—a perspective on the art, or an impression of the art, for people to really understand it.” Using the Mona Lisa as the best-known example, he says, if you included every bit of detail about the picture, then people aren’t really going to get a lot out of it.

Regardless, Mark Riccobono, president of the National Federation of the Blind, in talking about 3DPhotoWorks, stressed the importance of increased accessibility:

Too often people invent ways of describing art to blind people rather than creating authentic means for the blind to perceive visual imagery in nonvisual ways. This technology opens up new avenues for exploration and understanding and will enhance the experience for everyone. This technology also has the potential to allow greater participation by the blind in a wide variety of fields, especially the visual arts and STEM subjects.

—Susan Raab