A board is needed to incorporate a nonprofit, to get it tax exemption, to apply for a bank account, to properly file annual reports, and to do most important transactions. This is so because the principal roles of the board of directors are to represent the public (or membership) interests in the organization and to represent the organization as its legal voice.

The logic goes as follows: Nonprofit and for-profit corporations are not natural persons, meaning that they have rights and responsibilities but cannot read, write, think, or execute for themselves; corporations need a human group or person to do so and to guide decisions so that they positively influence the organization and the commitments it has made, including the choice of its chief executive and how it will carry out its mission.

In virtually every state, therefore, a nonfunctioning board is a cause for the involuntary closure of the organization by the attorney general, because this means it has no guiding or accountable voice—the CEO being the agent or instrument for implementing what that voice approves. What specific actions are required of the board to demonstrate and exercise its roles in guiding and representing the best for the organization? To fulfill these roles, the board must be able to accomplish at least the following essential tasks:

- Approve the budget.

- Review, sign, and assure submission of annual reports.

- Review and authorize personnel policies relevant to hiring, promotion, dismissal, compensation, whistleblowers, independent contractors, key employees, sexual harassment, and fairness to the disabled and other groups.

- Meet annually and as needed, even if only electronically.

- Review and approve plans of reorganization, growth, and contraction.

- Review and approve plans for major asset sales and acquisition.

- Review and approve major gifts, including the terms of the gifts.

- Review and approve the organization’s plans to do major borrowing.

- Review and approve the organization’s investment policy and plans to open banking and other financial accounts.

- Review and approve major changes in retirement, benefits, and compensation for all employees, with special focus on reasonableness for top executives.

- Review and approve amendments to the bylaws.

- Provide and be prepared to receive complaints and allegations of wrongdoing that affect the senior staff—its omission or commission, including conflicts of interest.

- Discharge and replace its members for reasons authorized by the bylaws.

- Create committees and hire consultants.

- Write policy and review status of its own membership for independence, conflict of interest, self-dealing, competence, performance of duties, and compensation.

- Be prepared to authorize lawsuits by the organization, receive them, and dispose of them by settlement agreed upon by them, if necessary.

- Authorize liability, bonding, and other insurance and indemnification.

- Authorize collaborations, other commitments of the organization, and their terms.

- Require accountability, transparency, loyalty, and conformity by key employees, and protect the identity and integrity of the organization.

- Request dissolution and carry out its terms.

- Approve changes in the organization’s name and address.

- Approve changes in the number, composition, qualifications, authority, or duties of the governing body’s voting members; and in the number, composition, qualifications, authority, or duties of the organization’s officers or key employees.

- State the requirements for a quorum or for any class of issue.

- State the conditions and procedures for calling emergency meetings.

- Keep records of its activities.

Board Members and Conflicts of Interest, Nonindependence, and Self-Dealing

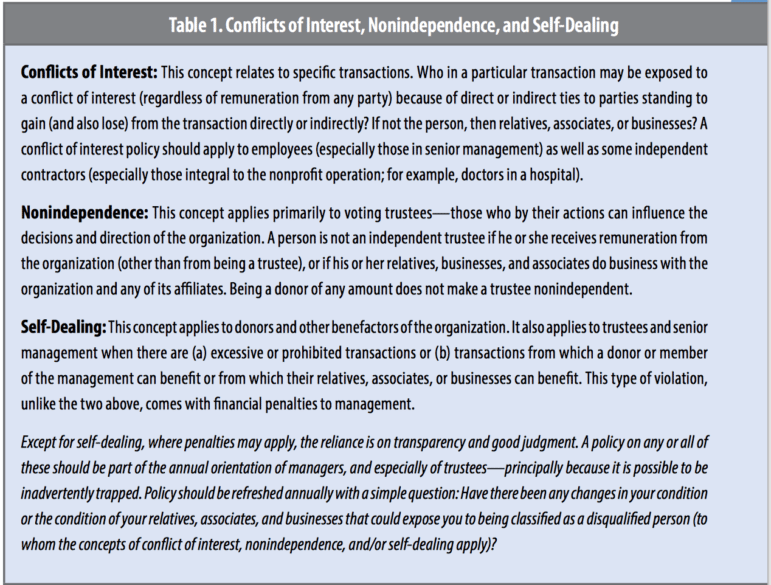

The relationship of the trustee to a family, to a business, and to the organization itself matters. Therefore, there should be a concern for conflict of interest (a concept that focuses on personal or private gains from a specific transaction), and concern for the independence of a board member (a concept that refers to the relationship of the board member to the organization: is he or she a part of the organization and therefore likely biased in favor of the organization rather than objective?). There should also be concern for self-dealing (a concept that describes using an organization to advance personal benefits when it is clear that the personal gains outweigh the gains to the organization).

The fact that a member may be nonindependent does not necessarily mean that the member has a conflict of interest. But it can raise the question: Is the person’s view likely tainted or biased? When a board member is not independent, that has to be recorded, but it is not prohibited. Interlocking directorates may, therefore, have several members who are nonindependent but not necessarily self-dealing. For a member of the board to be considered independent, all four of the following conditions must be met:

- The member may not be a compensated officer or employee of the organization, its affiliate, or other related organization, or any other with which the filing one does business.

- The member may not have received compensation exceeding $10,000 from any of the above during the reporting year.

- Neither the member nor a member of his or her family may have had an economic transaction with the organization or its affiliated or related organizations during the year.

- Neither the member nor a member of his or her family may have had an economic transaction during the year with an organization doing business with the filing organization or its affiliates.

A member is not considered to be nonindependent just because:

- The member receives compensation from the organization contingent upon his or her being a member of a recipient group of the organization.

- The voting member is a donor of any amount to the organization.

Obviously, these concepts of conflict of interest, nonindependence, and self-dealing need to be given further and keener attention, depending on one’s own organizational design and relationships (see Table 1).

Dealing with Possible Conflicts of Interest

A conflict of interest occurs when a person stands to gain from decisions he or she makes that are likely to benefit him- or herself, family, or business associates at the expense of benefit to the organization. A nonindependent board member may not necessarily have a conflict of interest vis-à-vis a particular transaction. A conflict of interest vis-à-vis a transaction may just as easily occur (if not more so) with an independent member of the board. A conflict of interest implies that the person has subordinated or is at the risk of subordinating his or her duty (loyalty) to the organization on an organizational matter to his or her own gain or the gain of a family member or business associate.

Every nonprofit organization needs to consider ways to avoid conflicts between the interests of the organization and those individuals in management, governance, and decision-making roles in the organization. The IRS has recommended that organizations consider adopting a conflict of interest policy that includes provisions to which these individuals should conform when considering transactions in which they have a potential, actual, direct, or indirect financial interest.

The Risk of Self-Dealing

Self-dealing is invariably a consequence of a conflict of interest. If the latter were the signal of a likely opportunity, the former is the action that takes advantage of the opportunity for personal, family, or business-related gains or the gains of another manager or independent contractor (such as excessive compensation).

Section 5233 of the California Corporations Code clearly defines self-dealing as any transaction involving the organization and in which one or more trustees or officers have a material financial benefit, unless: (1) the attorney general gave approval; (2) the organization entered into the transaction for its own benefit; (3) the transaction was fair and reasonable for the organization; (4) it was favorably voted for by the majority of the board, not including the affected members; and (5) the board had information that more reasonable terms were not available. In addition, the California law, as in most states, not only defines self-dealing but also gives the time period in which it must be reported or corrected and the way liabilities are shared. A sixth condition that is covered separately stipulates this. The penalty for the infraction of self-dealing may include the return of the property with interest, payment of the amount by which the property appreciated, and a fee for the use of the property. It may also include a disciplinary penalty for the fraudulent use of the assets of the organization.2

Again, self-dealing does not bar an honest, arm’s-length transaction that benefits the nonprofit and does not unduly favor the trustee or officer over others. These types of transactions should always be approached with very careful legal and ethical scrutiny and within the scope of a carefully crafted and existing policy. Discussions involving the questioning of the involved parties—as well as decisions—and the supporting or exculpatory information should always be retained.

Dealing with Nonindependence

Each member of the board has to be classified as independent or not, and if not, why and how. Moreover, there is no prejudgment that is correct about the relevance of nonindependence. A key employee who might also be a member of the board is nonindependent by virtue of his or her employment in the organization, and another member of the board who is not an employee may be nonindependent because his or her firm has a close relationship with the organization—such as sponsorship of its operations or services to it, or being a client of the organization (or vice versa). Knowing where board members may be coming from is important in evaluating the possible impact or perspective they might bring to specific board decisions—especially transactions with financial implications.

Standards at the Root of All Trustee Actions

At the root of conflicts of interest, nonindependence, and self-dealing are three simple standards: duty of loyalty, duty of care, and duty of obedience. Together, they define the fiduciary responsibility of the trustees and the officers of a nonprofit, both of whom can be held personally liable for monetary damages for breaching these duties. A trustee who behaves in conformity with these standards escapes personal liability for his or her action on behalf of the organization, even if the result is an error so serious as to cause the organization to lose its status. The standards guide actions; they do not judge their brilliance or consequences.

These standards recognize the possibility of error, so they judge only unintentional negligence—not whether the decision was fruitful or intelligent. The application of these principles in a court of law prohibits second-guessing as long as the trustees made their decisions in good faith. This is called the business judgment rule. What follows is an explanation of the three.

Duty of Loyalty

The duty of loyalty means that while acting in the capacity of a trustee or manager of a nonprofit, a person ought to be motivated not by personal, business, or private interest but by what is good for the organization. The use of the assets or goodwill of the organization to promote a private interest at the expense of the nonprofit is an example of disloyalty; in such cases, an individual places the nonprofit in a subordinate position relative to his or her own interest. The nonprofit is being used. One purpose of the annual reporting referred to above is to check on self-dealing.

Self-dealing is a form of disloyalty. As described earlier, self-dealing means using the organization to advance personal benefits when it is clear that the personal gains outweigh the gains to the organization. A trustee is not prohibited from engaging in an economic or commercial activity with the organization. Such a transaction can, however, be construed as self-dealing if it can be shown that: the trustee gained at the expense of the nonprofit; the trustee offered the nonprofit a deal inferior to what is offered to others or what the nonprofit could acquire on the open market; or, the nonprofit was put in a position of assuming risks on behalf of the trustee. A numerical amount, $5,000 or more, makes the self-dealing an illegal—not just an unethical—infraction.

Another form of self-dealing can occur when two or more nonprofits merge assets or transfer assets from one to the other, and they have the same trustees. Here, the issue is whether a good purpose is being served. Therefore, before consummating a merger, or any other major transaction, it is wise to set a barrier against self-dealing.

One might assume that a common way the board of trustees must defend the nonprofit organization against self-dealing is in cases of corporate officers abusing their trustee status for the benefit of their firms; however, this is not the case. A board will more likely need to defend its organization against the organization’s founder(s). It is not unusual to find that after years of personal sacrifice in calling the public’s attention to a good cause, founders of organizations confuse the assets of the nonprofit with their own, confuse the interests of the organization with their own, and begin to take dominion over these assets or install themselves or relatives in highly favorable tenured positions. Operating under the burden of loyalty, boards must separate these persons from the organization.

Duty of Care

The duty of care requires trustees of nonprofits to act in a manner of someone who truly cares. This means that meetings must be attended, the trustees should be informed and take appropriate action when needed, and the decisions must be prudent.

The test of prudence depends on state law. In many states, the trustees of nonprofits are held under the same rules that govern trustees of for-profit corporations. In these states, prudence can be construed to mean making decisions not unlike those expected of any other group of trustees faced with relatively the same “business” facts and circumstances. In other states, nonprofit trustees are held to a higher standard, where prudence means using the same wisdom and judgment that one would if his or her own personal assets were at stake. The first is called the corporate model and the second is called the trust model.

The duty of care can deny using ignorance as a defense. Therefore, it is inconsistent with this duty to allege that a trustee or manager does not hold any responsibility merely because he or she is unaware. To know is the duty. It is this duty that makes many compassionate but busy people reluctant to serve on nonprofit boards. In a real sense, they can’t care enough—that is, not in the legal sense.

Duty of Obedience

The duty of obedience holds the trustee responsible for keeping the organization on course. The organization must be made to stick to its mission. The mission of a nonprofit is unlike the mission of a firm. The mission is the basis upon which the nonprofit and tax-exempt status are conferred. Unlike a firm, a nonprofit cannot simply change its mission without the threat of losing either its nonprofit or tax-exempt status, or both.

Economic Transactions and the Trustees

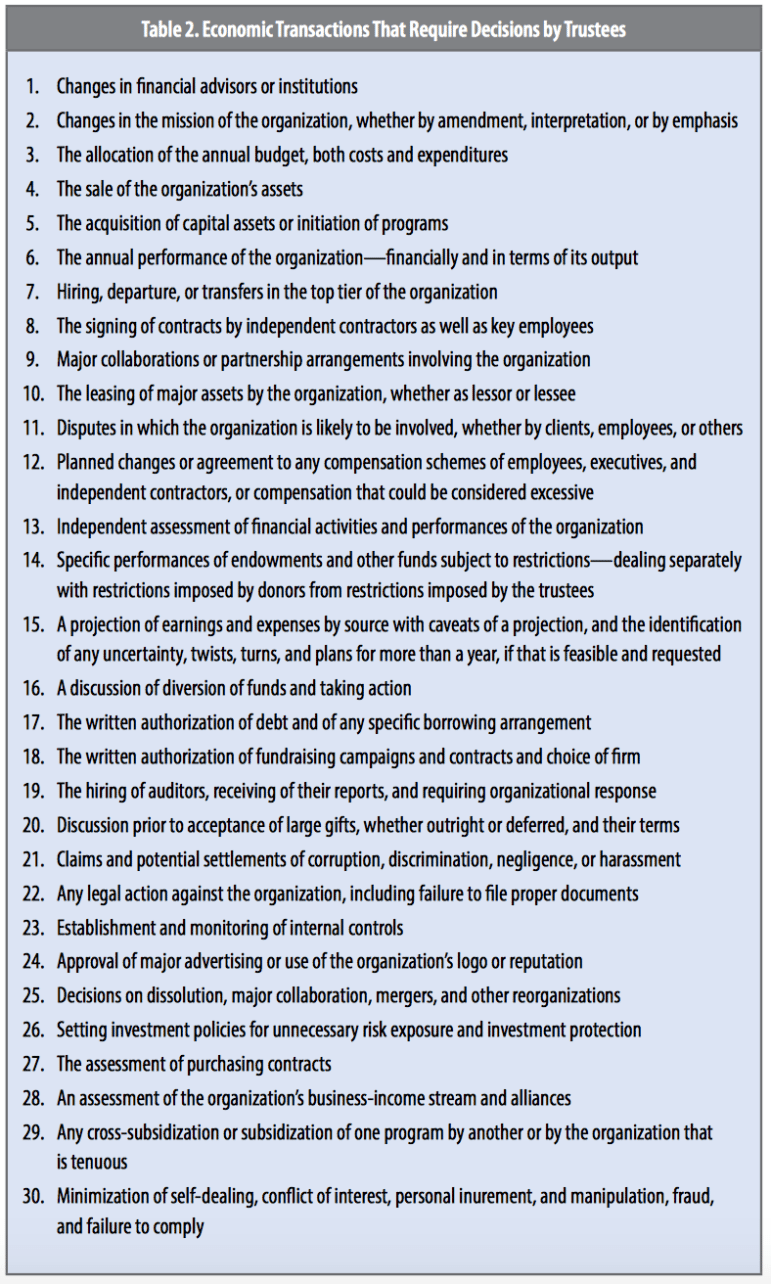

Table 2 (following) enumerates certain economic transactions that require decisions by the trustees—and, therefore, carry the possibilities of conflict of interest, self-dealing, corruption, malfeasance, and personal penalties on the trustees for failure to comply with the duties of loyalty, care, and obedience. The member may not be excluded from participation but may recuse him- or herself, or require a vote or permission by the board for his or her participation. Furthermore, these transactions come with the right of the trustees to be informed by the operating managers of the organization—and may even require the approval of the trustee either by bylaws, state laws, or by the other parties to the transaction. They are inescapable in the role of being a trustee.

Excessive Economic Transactions and Due Diligence

Every economic transaction has the potential for some form of compensation where—by a lack of exercising their duties of loyalty, care, obedience, and the additional duty of due diligence—trustees agree to or put forward a compensation that is offensively excessive. This occurs with compensation of key employees, the trustees themselves, and with independent contractors and vendors.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Trustees are responsible for negotiating and agreeing to executive compensation and key employee contracts. Key employees satisfy two criteria: (a) their full aggregate compensation of all types from the organization (its subsidiaries, its affiliates, and disregarded groups—joint ventures and corporations of which the nonprofit is sole member and must include in its 990 reports) exceeds $150,000 annually, and (b) they hold a position of responsibility for making the decisions concerning any of the key employees. The federal law, “Taxpayer Bill of Rights 2,” makes trustees disqualified persons. For purposes of compensation, a disqualified person is any trustee, manager, donor, or entity (and in the case of a hospital, any physician) who had substantial influence over the organization in the five years preceding the date of the “excess transaction.” Any firm in which a member of the board directly or through family relationship owns or controls 35 percent or more of the voting stock is itself a disqualified person. Therefore, the firm would also be limited in its economic relationship with a nonprofit organization. This is to prevent a member of a nonprofit board who is also a business owner—or who is related to one—from doing business with the organization and for excessive fees.

Any such disqualified person (the trustee or the firm that he or she—or his or her relatives—controls) who obtains excess benefits (such as overcompensation) can be subject to an excise tax of 25 percent of such an excess; and any disqualified person who knowingly participated in this agreement would additionally be subject to an excise tax of 10 percent of the excess up to $10,000. The focus of this law is on executive compensation, but it applies to all kinds of transactions—including the payment of trustees or any other disqualified person as defined above, or the payment in a sale of a product or service rendered by them. The law considers excessive compensation to any disqualified person to be self-dealing; for example, using the assets of the organization for personal benefit.

Participation in self-dealing is willful if the disqualified person engaged in the act voluntarily, intentionally, and consciously. Self-dealing refers to benefiting—or having some other related person benefit—excessively from a transaction. It can occur from an act or the failure to act when one is required to express an opinion or decision about that transaction and fails to do so. Therefore, liability also arises from silence and the lack of action to stop or to record objection to an excess benefits transaction—unless there is reasonable cause to believe that the trustee or other disqualified persons did not know of the transaction, and did not know that the transaction would be deemed self-dealing. Failure to have inquired about whether the transaction was an act of self-dealing, where this inquiry is clearly indicated, does constitute an act of negligence and could likewise result in being penalized by the imposition of the excise tax.

But when is compensation excessive? It is excessive when the compensation exceeds the economic value of the benefit the organization got in return or when the compensation is calibrated to the organization’s revenues or reflects personal inurement.

The law does provide for the organization to indemnify or insure the disqualified person against the cost of any penalty or taxes due to an “excess transaction.” It does, however, also require that this insurance or indemnification be included in the compensation. Hence, the more the organization covers for the disqualified person, the greater the tax or penalty on all disqualified persons found to have knowingly participated in the transaction.

The principal defense against excessive economic transactions is comparable compensation information—in other words, do comparable organizations justify what is being accepted or offered?

Duty of Organizations to Trustees and Their Rights

Trustees have the right to expect that the nonprofit organization has exactly the same duty to them as they have to the organization. They should expect obedience to their policies that are consistent with the mission of the organization. Trustees share liability for infractions; therefore, they should expect that their directions will be obeyed. It is they, rather than the employees, who represent the public interest. Timely and relevant information and interaction consultants (including auditors, compensation experts, lawyers, and the chief executive of the nonprofit) are first defenses against unwitting self-dealing, conflict of interest, and general failure to perform their duties of loyalty, care, and obedience. Trustees, therefore, have a right to know, and the organization has a duty to keep them informed.

Accordingly, trustees should expect a duty of care directed toward them. As their duty of care toward the organization means that they need to be informed and to act prudently on behalf of the organization, they should expect that they will be kept informed about those things that matter. These include being kept up to date on major changes in the organization’s direction or assets, annual budgets and financial statements, changes in key employees, new risks to which the organization is exposed, employee compensation packages, and evaluations of the organization’s performance.

The duty to the trustees also encompasses loyalty. This concept implies a protection of the trustees. Trustees have a right to presume that the relationship between them and the organization is aboveboard (so to speak), at reasonable arm’s length, and that the organization does not expose any trustee to personal or professional risks—even if it forewarned him or her that such risks might be present. Put simply, they have a right to expect that they are not being used or “set up,” that the information given them to form the basis of their decisions is as clear, complete, correct, and relevant as possible, and that the organization will not act imprudently.

Consistent with the exercise of prudence, trustees may rely on information they obtain from appropriately assigned employees, accountants, lawyers, engineers, and other experts. Relying on the expertise of such persons is an act of prudence and not necessarily a skirting or shifting of responsibility.

In the Guidebook for New Hampshire Charitable Organizations, New Hampshire’s attorney general advises that directors should have the following specific rights (in addition to others):

- To have a copy of the articles of organization (incorporation or deed), by-laws, and other documents that are necessary to understand the operations of the organization.

- To inquire about an orientation session for board members and about a board manual containing the policies and procedures for the organization.

- To have reasonable access to management and reasonable access to internal information about the organization.

- To have reasonable access to the organization’s principal advisors, including auditors and consultants on executive compensation.

- To hire outside advisors at the organization’s expense.3

Observe that these rights are consistent with exercising the duty of care, and with the law’s protection of trustees and officers if they rely on the expert judgment of persons such as auditors and accountants, lawyers, and investment advisors. They are also consistent with the organization’s duties to the trustees.

These rights translate to the trustees’ right to know, be informed, and have their actions followed. Some of these are required by law, such as trustee approval of amendments; some are required by practice, such as a bank’s stipulation that a trustee resolution be supplied before it extends a loan; some of these are subtle, such as informing trustees about major transactions so that they can determine if there is a potential conflict of interest; and some of these are early warnings or pleas for help, such as giving a projection not simply of the annual data but of what they may look like under certain projections—such as if trustees continue to operate as they have been.

Liability of Trustees

No matter how much protective action is taken, there is always the possibility of a trustee’s being sued or involved in a lawsuit against the organization. How does the organization protect the trustee?

First, by timely information as discussed above, so that the trustee can take adequate action; second, by covering the trustee through insurance and indemnification; and third, by disclosures.

The board of trustees of a nonprofit organization may be sued by (1) the members in a so-called derivative suit, whereby the members are suing the trustee on behalf of the greater good of the organization; (2) a third private party; (3) a government; and (4) one of its own members or employees. Liability may arise either for actions taken or for the failure to act. Furthermore, in some instances, liability may arise because of the actions of other trustees or officers. For example, a trustee can be held liable for failing to block an inappropriate action by other trustees or by management. The duties of care and loyalty mean that a trustee cannot choose to look the other way when an officer or another trustee may be involved in actions that are wrong.

This liability threat would discourage many good people from serving nonprofits. If the trustee can be held personally liable, then he or she faces the possibility of being sued and having to pay monetary damages out of personal resources. Even if monetary damages are not assessed, the trustee faces the unpleasant possibility of having to spend time and resources in a personal defense. In addition, there are the emotional and social costs.

Recognizing this deterrent, many states have taken actions to limit a trustee’s personal liability. For volunteers as well as trustees, states range from no protection to protection only if the act was not intentional, was the result of negligence or breach of fiduciary responsibilities, was a knowing violation of the law, or was a result of a reckless action or one done in bad faith.

In general, an officer or trustee is immune from civil suit for conducting the affairs of a nonprofit unless the action taken is willful or wanton misconduct or fraud, or is gross negligence, or if the person personally (or through a relative or associate) benefited from the action taken.

A trustee is liable for unlawful distributions of the assets of the organization. An unlawful distribution can be one that is inconsistent with the mission of the organization, inconsistent with the bylaws and tax-exempt laws, outside the powers of the organization, and for private gains of the trustee or associates. A loan to a trustee is just one type of unlawful distribution. Using the assets for political purposes is another, and so is excessive executive compensation.

Not only are the trustees who voted in favor of the unlawful distribution liable, but so are all other directors who failed to voice an objection. Arizona 10–3833 requires that objections be noted in the minutes of the meeting when the act was taken or by 5:00 p.m. the next business day. It further states, “The right to dissent does not apply to a director who voted in favor of the action.” Still further, any trustee found liable for the unlawful distribution shares that culpability and can be held equally liable with all trustees who voted affirmatively, all trustees and members who shared in the distribution, and all who failed to dissent in the manner prescribed by law.4

Even though the nonprofit has the power to indemnify a trustee or officer, some states specify the conditions under which such indemnification can be offered. In Mississippi 79–11–281, indemnification can be offered only if the trustee (1) conducted him- or herself in good faith and (2) believed that the conduct was in the best interest of the organization—or at least not contrary to its best interest or those of its members.5

The nonprofit may not indemnify the trustee or officer when he or she is judged to be liable to the nonprofit or in any situation where he or she benefited improperly. Indemnification may be limited to reasonable expenses incurred. Generally, reimbursement may occur only after the case is disposed, but Mississippi, as an example, provides for payment in advance. However, the trustee must provide a written statement attesting to having undertaken the action in question in good faith, stating that the trustee promises to repay the sum if the judgment is against him or her, and declaring the act not one that would otherwise preclude indemnification. A trustee that is entitled to indemnification may turn to the court to have such indemnification paid by the nonprofit. If the proceeding is against the organization rather than against the trustee, the trustee may be indemnified by the organization for his or her expenses. This is the case if the trustee acted in good faith.

…

A board of directors or trustees of a nonprofit organization is an essential part of the design of the organization and how well it abides by its mission, the expectations of its members, its clients, and state, local, and federal governments. The way a board is constructed is important because it affects the representation of various interests and the efficacy of the board.

The composition has to do with the number and distribution of persons on the board and the way it is divided by function. The functions are not perfunctory; they facilitate the capacity of the board to carry out its principal purpose of being the voice of the organization and the various interests that the organization serves. To do this competently involves carrying out a variety of specific activities and first being true to the organization in doing so. This means putting the organization first (loyalty to it and the care it takes to do that well). Self-dealing is to be avoided; conflicts of interests are to be minimized.

The issues here are not just ethical; they are also legal and therefore given attention as core duties of the board. The single best advice: board members must care sufficiently to be fully informed, fully involved, and fully compliant. Short of this, there is personal risk of liability and organizational risk of failure—to the detriment of those the organization was intended to serve.

The success of the board depends upon all that has been outlined above, but to carry out any of these best practices requires that the organization—especially the chief executive—recognize the importance of providing the board with timely information. Society depends upon nonprofit organizations for a variety of essential functions—from education to health, art to social services, and housing to general welfare, to name a few. The success of these organizations in serving the public depends not only upon monetary resources but also on the ability of these organizations to function in an orderly and efficient manner. When a nonprofit organization fails, promises fail—and so do the expectations of the public and the direct clients and donors. And society has one organization less that it can call upon to provide needed services. The key to avoiding failure is the way the organization is managed—and at the very top of the management pyramid is the board of directors.

Notes

- Herrington J. Bryce, “Decision-Making and Governance Structure in Lessening the Burden of Government,” in Nonprofits as Policy Solutions to the Burden of Government (Berlin, Germany: De|G Press, 2017): 125–43.

- “CORPORATIONS CODE – CORP, TITLE 1. CORPORATIONS [100 – 14631], DIVISION 2. NONPROFIT CORPORATION LAW [5000 – 10841], PART 2. NONPROFIT PUBLIC BENEFIT CORPORATIONS [5110 – 6910], CHAPTER 2. Directors and Management [5210 – 5260], ARTICLE 3. Standards of Conduct [5230 – 5239], § 5233,” California Legislative Information.

- Guidebook for New Hampshire Charitable Nonprofit Organizations, 1st ed. (Concord, NH: Office of the NH Attorney General Charitable Trust Unit, 2005.

- “§ 10-3833. Liability for unlawful distributions,” Arizona State Legislature.

- “2013 Mississippi Code, Title 79 – CORPORATIONS, ASSOCIATIONS, AND PARTNERSHIPS, Chapter 11 – NONPROFIT, NONSHARE CORPORATIONS AND RELIGIOUS SOCIETIES, MISSISSIPPI NONPROFIT CORPORATION ACT, § 79-11-281 – Indemnification of director, officer, employee, or agent.”