December 10, 2017; ProPublica

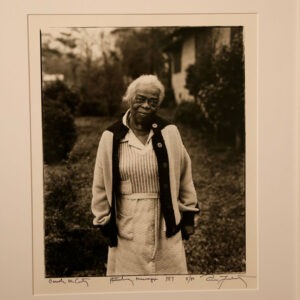

Following the tragic death of a highly educated and accomplished African American mother three weeks after giving birth, a tough question remains unanswered: If education, income, and a strong support system cannot protect black women from dying during and shortly after childbirth, what can? In collaboration with NPR, ProPublica told the story of Shalon Irving, an epidemiologist working with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to, ironically enough, eliminate health inequities.

When we hear of high pregnancy-related death rates for black women, a stereotype is often presented of a low-income woman who is uneducated and not medically compliant. Yet, Shalon completely contradicts this stereotype and still met the same fate. With two PhDs, two master’s degrees, and a book on the way, Shalon’s resume was impressive, to say the least. Her story shows that even when controlling for the other social determinants of health—economic status, education, employment—race and racism still play an enormous role in determining the outcomes for black women in the U.S.

According to ProPublica, compared to white mothers, black mothers are “243 percent more likely to die from pregnancy or childbirth-related causes.” Even when compared to white women with the same medical complications that often lead to maternal death, black mothers are still two to three times more likely to die. Perhaps the most troubling statistic is that “black expectant and new mothers in the US die at about the same rate as women in countries such as Mexico and Uzbekistan.”

Dr. Raegan McDonald-Moseley, chief medical officer for the Planned Parenthood Federation of America and one of Shalon’s good friends, speaks of the lesson gleaned from her death,

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

It tells you that you can’t educate your way out of this problem. You can’t health-care-access your way out of this problem. There is something inherently wrong with the system that’s not valuing the lives of black women equally to white women.

The latest research indicates that the racism that black women face, overt and implicit, throughout their lifetimes can lead to a state of chronic stress on their bodies. Michael Lu, former head of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau at the Health Resources and Services Administration, explains, “It’s the experience of having to work harder than anybody else to get equal pay and equal respect. It’s being followed around when you’re shopping at a nice store, or being stopped by police when you’re driving in a nice neighborhood.” In fact, this chronic stress has been shown to literally age women, equating the health status of a thirty-year-old black woman to that of a forty-year-old white woman.

NPR and ProPublica collected over 200 stories of African American mothers, and every story featured a common theme: “the feeling of being devalued and disrespected by medical providers.” These stories are gut-wrenching, as women speak of breathing problems that were “blamed on obesity when in fact [their] lungs were filling with fluid.” Or, “the Arizona mother whose anesthesiologist assumed she smoked marijuana because of the way she did her hair.” One Brooklyn woman said, “Sometimes you just know in your bones when someone feels contempt for you based on your race.”

It is difficult to understand how the health industry could be plagued with racism when we think of those in the medical field as educated people working to help others. Yet, NPR and ProPublica’s findings are consistent with NPQ’s own analysis. Martin Levine’s “The Invisible Bias Epidemic: Addressing Racial Disparities in Medical Treatment” looked at how implicit bias results in very different HIV lifetime risk for the African American population versus the white population. In “Race and Health, and Doulas for Social Justice,” Megan Aebi asserted that pregnancy-related health disparities for African American women aren’t “simply a healthcare quality issue; it is a social justice issue.” Rick Cohen discussed a two-tiered “separate and unequal” system of healthcare delivery distinguished based on race and socioeconomic status.

The convoluted nature of the problem is well documented, but the medical community has yet to propose a solution. While we have seen grantmakers in the health field who seek to address the social determinants of health, few are specifically tackling the systemic issue of racial health disparities. Perhaps Monica McLemore, a professor of nursing at the University of California, San Francisco, is correct in her suggestion. “That’s a real problem that across the spectrum that black women are not feeling listened to and respected- that’s a structural problem. The health sector doesn’t want to admit how much of this is about us.”—Sheela Nimishakavi