July 11, 2018; Color Lines

Nonprofits working in communities continue to learn more about how intersectional identities and issues impact service provision. Poverty, housing insecurity, employment discrimination, and social isolation all influence the care and health of the American Indian and Alaskan Native (AI/AN) communities. AI/AN adults face significant barriers, especially women, who are burdened by the additional barrier of institutional racism. This impacts women of color and AI/AN women even when they avoid other barriers like poverty and housing insecurity. While research on the health of AI/AN women is limited, a study by the Center for American Progress has found these impacts are similar to those faced by Black women.

The study, released on July 9th, found that the institutional racism faced by AI/AN women is one factor driving high maternal and infant mortality rates for Native Americans. In 2015, mortality rates for AI/AN babies under one year old was 8.3 per 1000 births, compared to only 4.9 deaths per 1,000 births of non-Hispanic white babies. Mortality rates have declined over the years for all ethnic groups except AI/AN babies. According to an article in Rewire.News, “Native American infants are twice as likely as non-Hispanic White infants to die from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), and are 70 percent more likely than non-Hispanic White infants to die from accidental deaths before the age of 1.”

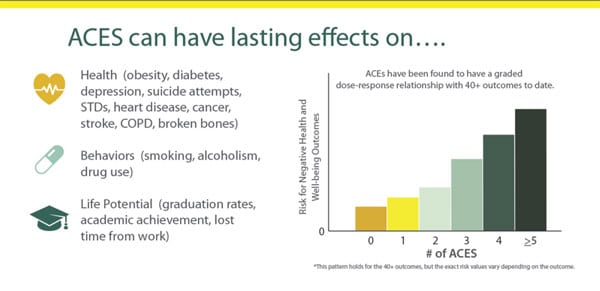

Not only do barriers stemming from racism, such as class, insurance access, and healthcare access impact infant and maternal health, biological and neurological advances have found the same is true of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including the “legacy of chronic trauma and unresolved grief across generations” as a result of colonialism, genocide, forced migration, boarding schools, and relocation.

Historical trauma is transferred through generations via biological, psychological, environmental, and social means. These traumas not only impact people of color from accessing care, but they directly impact their health. Individuals with high ACEs scores (more traumatic childhood events) are more likely to develop health problems, including diabetes, liver disease, fetal health issues, high blood pressure, and addiction and can even suffer early death in some cases.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

And while trauma may be in the DNA of American Indians, “love is there, too” says Mike Carney, a doula in the Lakota Nation. American Indian and Alaskan Native communities have many culturally grounded approaches that can interrupt the cycle of historical trauma, including cradleboards—indigenous baby carriers that have been shown to reduce SIDS—and welcoming ceremonies to bring the child to the tribe and family with open arms.

Also, last month, NPQ wrote about a community initiative in Fresno that improves community resilience through the use of “a strength-based, holistic, and youth-friendly self-assessment tool grounded in the Medicine Wheel.” In the tool, as developed by the group, “the four directions—east, south, west, north—represent the lifespan (i.e., infancy, childhood, adulthood, elderhood); the area of health (i.e., mental, physical, emotional, spiritual); and the GONA [Gathering of Native Americans] themes (i.e., belonging, mastery, interdependence, generosity).”

These ceremonies and traditions are empowering, and by incorporating practices and beliefs, especially those that support infant and maternal health (physical and emotional), agencies working with American Indian women and their children can increase the support and wellness of their clients. A level of cultural competency and humility needs to be present in all nonprofits, especially in the areas of health and wellness.

Because of these institutional barriers and forms of aggression, as well as the low number (two percent of the population) of AI/AN individuals in the United States, medical files and records often underreport the number of AI/AN patients, so the numbers of infant and maternal mortalities may be higher. Nonprofits often struggle with data collection in the face of traumatized clients, confidentiality requirements, and fears of being intrusive.

However, the need for government-level intervention and services in the community cannot be adequately measured without this data. And when working with clients who disclose they do have insurance, for instance, consider that they may be receiving health services through the Indian Health Services (IHS) program, which remains underfunded, lacks adequate emergency and child health providers, and has long wait times. As with many things, access does not mean adequacy.— Ember Urbach