A new story from the Daily Beast and the Marshall Project shows that although voting restrictions for ex-offenders are getting looser in a handful of states, many of those potential new voters aren’t aware of changing laws—at least in Alabama.

Alabama denies residents the vote if they have been convicted of a “crime of moral turpitude.” However, on May 25, 2017, Governor Kay Ivey signed a bill defining just which felony convictions result in a denial of voting rights. The Definition of Moral Turpitude Act lists 47 specific crimes that trigger the loss of voting rights, superseding the old system in which individual county registrars determined which crimes were of moral turpitude. As the Alabama ACLU observed, “Voting rights can be restored to many whose crimes are not on this list and will not be refused to those who might have been discriminated against in the past.” Advocates said the new law would impact thousands. However, the implementation of the new law, which went into effect last August, did not have the immediate impact many wanted.

Immediately following the passage of the Moral Turpitude Act, some ex-felons were informed that they needed to fulfill all financial obligations related to the felony—court fines, legal fees, and victim restitution. Voting rights advocates called these financial barriers for ex-felons who wish to vote unconstitutional, saying they essentially serve as a poll tax. In Alabama, about three-quarters of ex-felons who have served time still owe a financial obligation, and the median outstanding debt is over $3,500. However, the state eventually clarified that for people whose voting rights were restored under the Moral Turpitude Act, financial obligations would not serve as a barrier to voting.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Another barrier to the implementation of the new rules: County registrars who aren’t aware of the new list of “crimes of moral turpitude.” Each of Alabama’s 67 counties has a board of three registrars. Although Secretary of State John Merrill has said that registrars in all counties have received instructions on what they need to do to comply with the law, Al.com reported in October that when the news site surveyed registrars, several were not aware of the new rules.

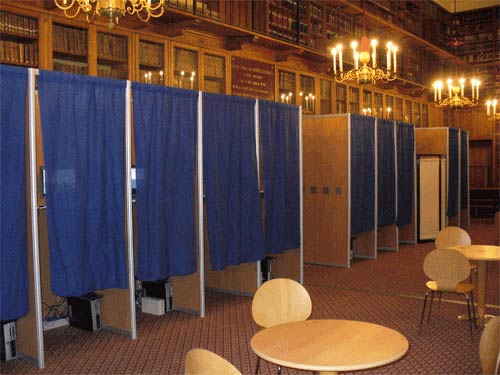

The law also did not establish a mechanism for notifying ex-felons who became eligible to vote of their eligibility. A federal judge turned down a case brought on behalf of 10 Alabama citizens by the nonprofit Campaign Legal Center, which wanted to require the state to educate the public about the new law. Earlier this year, the Campaign Legal Center and the Southern Poverty Law Center instead launched the Alabama Voting Rights Project, which uses volunteers and nonprofit monies to knock on doors and distribute information in libraries, churches, and jails.

The Campaign Legal Center has projected that tens of thousands of Alabama residents convicted of crimes could now be eligible to vote; they just may not know it. The responsibility for educating these residents is part of the ongoing debate on voting rights for ex-felons.—Lauren Karch