September 13, 2018; Washington Post

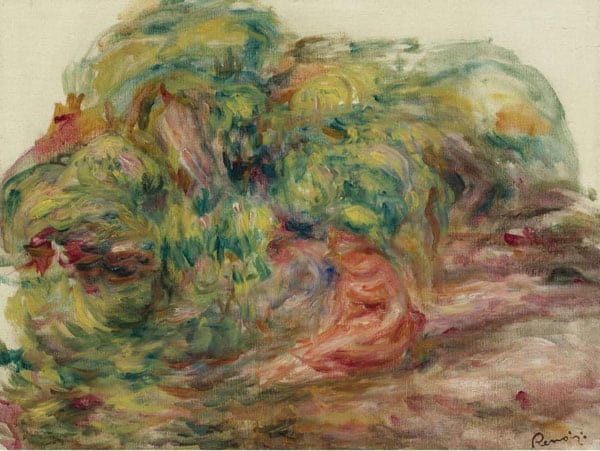

Kudos to a New York nonprofit, the Museum of Jewish Heritage, for playing a part in the heart-wrenching saga of a Jewish family being reunited with their Nazi-stolen artwork, specifically a spectacular Renoir painting called Deux Femmes Dans Un Jardin.

The museum livestreamed the restitution ceremony on September 12th on its Facebook page, as representatives of the local US Attorney’s Office and FBI presented Sylvie Sulitzer with the painting.

Meagan Flynn, writing for the Washington Post, recounted the family’s riveting tale:

Alfred and Marie Weinberger escaped Nazi-occupied Paris at the onset of World War II, but they couldn’t take their paintings with them.

The Jewish couple fled to the French Alps and left their paintings—several by Pierre-Auguste Renoir—sequestered in a Paris bank vault. One was Deux Femmes Dans Un Jardin (Two Women in a Garden), one of the last paintings Renoir made before he died in 1919, when his rheumatoid arthritis was so severe he had to tie the paintbrush to his hand to grip it.

The Weinbergers would never see it again. On Dec. 4, 1941, the Nazis plundered Weinberger’s collection.

Alfred Weinberger would spend much of his life trying to get his paintings back. And he would find some—but never Renoir’s Two Women in a Garden. It would instead travel around the world, changing hands and eluding the Weinberger family. Then, in 2010, Weinberger’s granddaughter, Sylvie Sulitzer, with German attorneys, set out to recover the missing 1919 Renoir.

It’s become a very familiar story, popularized in movies like Woman in Gold and The Monuments Men, as descendants of Holocaust survivors increasingly seek to find and reclaim stolen artwork from museums here and abroad. However, the Weinbergers’ painting ended up in several private collections, according to the Museum of Jewish Heritage’s website.

The Renoir resurfaced after the war at an art sale in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 1975. It subsequently found its way to London, where it was sold again in 1977, and then appeared at a sale in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1999. Ultimately, the Renoir found its way to Christie’s Gallery in New York, where it was put up for auction by a private collector in 2013.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

It was then that Ms. Sulitzer learned of the pending sale and made a claim to the work as part of her grandfather’s collection. Christie’s alerted the FBI, and ultimately the purported owner of the work voluntarily agreed to relinquish its claim.

Sulitzer lives in France and traveled to New York to receive the painting this week.

Because the Nazi’s careful records of stolen artifacts, created by a division known as the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, or ERR, have now been digitized by a collaborative effort called the ERR Project, it seems likely that claims from Jewish families like the Weinbergers will be increasingly common. The ERR Project database has a fascinating backstory of its own:

With support from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference), the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has over the past decades brought together microform records of the Holocaust from archives all over the world.

At the Washington Conference on Holocaust-Era Assets co-hosted in 1998 by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum with the U.S. Department of State, attention turned to the importance of archival records in understanding the plunder of art and other cultural property by the Nazis and their allies.

Subsequently at a seminar presentation at the Museum in February 2000, Patricia Kennedy Grimsted made an appeal for a virtual compendium of the widely dispersed records of one of the most important Nazi cultural looting agencies, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR).

This idea was discussed with interest by delegates from many countries later that year at the Vilnius International Forum on Holocaust-Era Looted Cultural Assets in October, 2000, where Dr. Grimsted suggested that a model project would be to digitize the registration card files produced by the ERR of art taken from French Jewish collections and held by the National Archives of the United States and to bring them together with the ERR photographs of those same artworks held by the Federal Archives of Germany (Bundesarchiv).

Years in the making, the online database now includes more than 30,000 art objects, mainly taken from Jewish families in German-occupied France, and is searchable by owner or object.

The Museum of Jewish Heritage, which describes itself as a living memorial to the Holocaust, is rightly celebrating this success story with a special exhibition of the painting and free admission through Sunday while it’s on display. (This recent NPQ story examined the benefits and drawbacks of free museum admission, albeit within a different context.)

In an era of rising hate speech and polarization, the story of a long road to what Sulitzer deemed “justice” seems like feel-good news we can all get behind. Sadly, Sulitzer told the Post that she may need to sell the painting for financial reasons. Perhaps her story will yet have another, Hollywood-style twist.—Anna Berry