October 22, 2018; Pasadena Star News

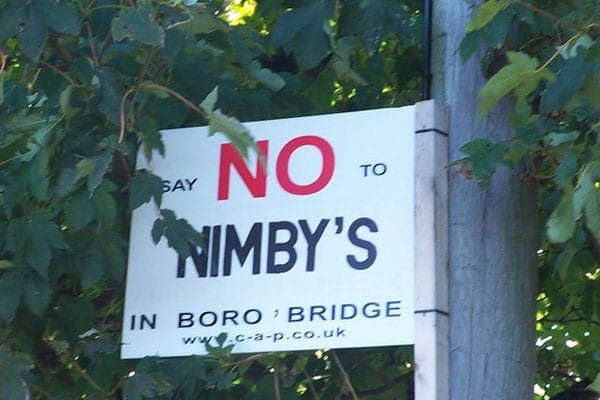

To label opposition to social housing projects as “NIMBY” (“not in my back yard”) is an oversimplification that does little to discourage the type of harmful hyperbole that is typical of NIMBY arguments:

- “The problem is just being moved from somewhere else, why is it our problem now?”

- “This is going to bring drugs/crime/disruption to our neighborhood!”

- “We paid taxes for a nice neighborhood, not one that is full of transient strangers.”

It is certainly understandable when nonprofits—often simultaneously in the trenches providing direct services as well as driving social policy progress for addressing America’s massive homelessness issues—are frustrated by these mostly spurious arguments. But citizens do deserve to be properly consulted about significant changes in their neighborhoods (and, indeed, will demand it), and there are consequences when residents feel surprised. This only feeds into NIMBY thinking and supports a perspective that a particular community is being victimized.

The all-too-familiar pattern of residents uniting around NIMBY themes is currently in full view in Pasadena, where plans for a “permanent supportive housing solution” (proposed for what is currently a Ramada Inn motel) quickly led to what has been described as a “raucous community meeting.” This was fueled to some extent by a deliberate misrepresentation of the approvals process, in the form of a fabricated letter attributed to city officials.

“It very quickly devolved into a shouting match,” said project proponent and Union Station Homeless Services CEO Anne Miskey. “Nobody was listening to the fact, or any of the research, that it’s been done successfully here in Pasadena.”

Indeed, Union Station owns and operates three supported housing projects in the Pasadena area, including a former YMCA building that now boasts 142 units with an impressive 95 percent retention rate, meaning that becoming a resident of the building means bringing an end to homelessness for almost everyone who moves in.

A crowd of more than 200 turned up at a local church to express their opposition to the project.

“We don’t want them to open up right across the street from our children’s school,” parent Rita Elkaddoum said in an interview. “There are other parts of Pasadena where they could open this up—where it’s not dead smack in the middle of Pasadena where you have children and schools and houses.”

St. Gregory A. & M. Hovsepian School principal Shahe Mankerian chimed in with a claim that the planning ordinance making such a project possible in the first place came into force with “no feedback or communication with the community.” Factually speaking, this is untrue. The Planning Commission spent the summer workshopping the motel conversion ordinance, and City Council made many changes in response to these consultations before introducing and approving a final draft earlier this month. But as the project proponents are learning, playing whack-a-mole at this stage won’t sway those who feel like they have been tricked by a devious process and are reacting with charged arguments about perceived threats of drugs and violence to schoolchildren.

Council member Margaret McAustin, targeted as one of the false signatories of the doctored letter used to rile up the crowd, rightly identified the need for a “larger conversation” to frame the problem and establish a foundation for these types of projects: “what can we do and what should we do to as a city to help homeless folks who are from Pasadena.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In what is hopefully not a “too little, too late” move by Union Station, Miskey says they are bringing on a new staff member who will be focused on community engagement, and will be tasked in part with helping share stories of what the supported housing experience is like—for those who directly benefit, as well as the positive experiences of surrounding communities.

This work will start with helping community members understand the distinction between the supported housing model and what most of the raucous 200 were actually picturing: a conventional homeless shelter, which features the key failing that it attracts and supports homeless people who tend to remain homeless.

Hidden beneath all the distractions of surprise, fake letters, and stereotyping, the Union Station model reflects a housing-first best practice that has been championed for years by researchers, advocates, and self-advocates who have been lifted out of homelessness. Although not everyone fits the model, “housing first” is essentially the only game in town for actually reducing homelessness rather than simply making it less horrible to endure, as with shelters and other non-permanent programs.

Miskey says the proposed Ramada project will feature on-site assistance with employment, education, counseling, life-skills training, budgeting, and connections to health care. Case managers will work with residents to anticipate and prevent difficulties, and as needed, deal with serious problems as they arise.

While community residents have the right to voice their concerns (and it must be acknowledged that the plan for rolling out the information seems woefully inadequate) there’s also an obligation to address homelessness and all the suffering that it brings.

At last count, Pasadena had over 675 homeless individuals, representing a 28 percent increase over the most recent two years. “This is a huge problem for the city and, really, for the region,” said Mayor Terry Tornek, pointing to recent headlines in Los Angeles and Santa Ana.

What is occurring in Pasadena is an issue being seen across the country: people who were never homeless before are being priced into homelessness by housing costs or rents they can’t afford.

The desperate need is also further reason why nonprofits and government must work better together to explain the facts, share the human impact of their work, and build a partnership with all citizens for addressing this catastrophe.

Strategies for fighting homelessness, including new builds or conversions, cannot continue to be viewed as something that is “done to people who already have homes.” Many millions of Americans are just one bad break away from being on the streets themselves—and wishing that someone would treat them like neighbors.—Keenan Wellar