Last month, more than 150 people crowded into a standing-room-only event in Oakland, California. (A video from the event is available here). Hosted by Justice Funders, which describes itself as “a partner and guide for philanthropy in reimagining practices that advance a thriving and just world,” the convening had a decidedly activist orientation. Speakers and participants were not there to talk about doing charity well, but rather about transforming philanthropy to its core.

Justice Funders’ executive director Dana Kawaoka-Chen set the tone with a bold call to action. Philanthropy, Kawaoka-Chen said, should be “redistributing all aspects of well-being, democratizing power, and shifting economic control to communities.”

A central framework around which Justice Funders orients its work is called “Just Transition.” With a new publication launched at the convening, Resonance: A Framework for Philanthropic Transformation, Justice Funders offers foundations and other philanthropists specific strategies for applying its tenets to the practice of philanthropy.

What Is Just Transition?

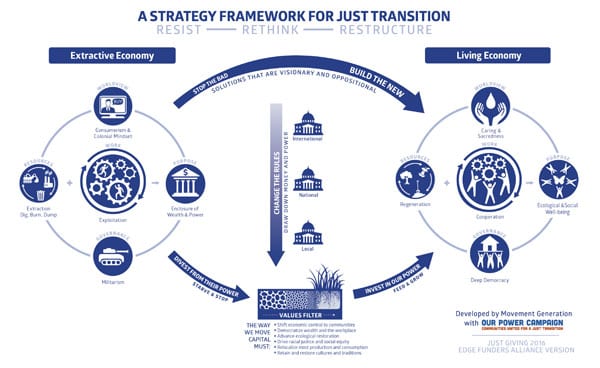

For those not familiar with the term, Just Transition is a framework for transforming our extractive economy to a regenerative one—one that both addresses climate change and overall well-being. In the US, it has been popularized by such groups as the Climate Justice Alliance and Movement Generation. Central to this approach are the notions of reciprocity and interdependence among human groups and with the living world. Just Transition principles today inform the work of activists across and at the intersections of many movements for social justice worldwide. For Justice Funders, the challenge is not merely to fund these movements, but to participate in a Just Transition themselves.

It is an auspicious time to be introducing a Just Transition-informed guide. Newly-elected Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has, with the introduction of the Green New Deal (GND), brought climate change and the necessary economic transitions to address it into the broad public discourse with a renewed energy. As the Climate Justice Alliance has commented:

The GND is the first time in many years that a proposal of this type has been presented by a number of members of a major US political party. It proposes to tackle climate change and inequality simultaneously, while revolutionizing conditions for workers. It is a much-needed aggressive national pivot away from climate denialism to climate action with large-scale federal legislative and budgetary implications.

Thus, this philanthropic framework built around Just Transition arrives in a different context than it would have even six months ago. The opportunity and even pressure for philanthropy to change practices to support an economic transformation that can save future generations is greater than ever.

As Kawaoka-Chen noted in her opening remarks, Resonance joins a body of recent philanthropic self-critique, including the works of Anand Giridharadas, Rob Reich, and Edgar Villanueva. Clearly, at least among progressive philanthropies, the felt dissonance between legacy practices and urgent challenges such as income inequality and climate change is intensifying. That dissonance is, of course, what Resonance is meant to replace. In fact, Justice Funders invokes the language of music metaphorically across its work. In 2015, they published a report called The Choir Book: A Framework for Social Justice Philanthropy. Their community of practice for philanthropic change agents is called the Harmony Initiative. And, last month’s convening began with acclaimed vocalist Tossie Long leading the room in a three-part rendition of the Ben E. King song, “Stand by Me.” The challenge, Justice Funders argue in their latest publication, is that “funders are not singing the same song, in the same key, let alone in harmony” (Resonance, introduction).

Stories of Just Transition

The convening was entitled State of the Movement: Funders and Frontlines Building Community Power and featured storytelling by movement leaders and funders actively working to find that harmony. There was a noteworthy lack of the kind of performativity, false humility, or obsequiousness that so often plague spaces designed for philanthropic and nonprofit leaders to come together for dialogue. This is perhaps not surprising. The movement leaders, while they mostly worked in nonprofit organizations, hardly led with their “nonprofit professional” identities, and these funders are, per Just Transition principles, actively attending to transferring excess power away from their institutions and toward the communities they fund. This all makes for very different and refreshing dynamics.

Jess Jollett of Lift Up Contra Costa Action, from a county to the northeast of San Francisco experiencing intense migration of displaced San Francisco and Oakland residents, shared their coalition’s success in getting the first Black woman elected as district attorney in Contra Costa County’s history. James Head, CEO of the East Bay Community Foundation, talked about how community foundations need to pivot to support social movements and increase civic engagement. Aaron Tanaka of the Center for Economic Democracy, in an honest and witty banter with long-time funder David Moy of the Hyams Foundation in Boston, described their experiences with new economic models—from green worker co-ops, to participatory local budgeting, to a democratically governed investment fund called Ujima.

In her remarks, Doria Robinson, a third-generation resident of Richmond, California, and executive director of the urban farming organization Urban Tilth, said, “It’s not about programs anymore. It’s about us not being victims of our circumstances.” And Crystal Hayling, who runs the Libra Foundation, asked fellow funders, “What does it mean to let go, to stand on the side?” She quoted Frederick Douglass in saying that funders cannot espouse liberation and at the same time “depreciate agitation.” Instead she argued, “Our job in philanthropy is to fund the struggle.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Woven throughout these talks was the theme of community self-determination, including in the generation and deployment of financial capital. And the fact of the matter is that institutional philanthropy, as traditionally practiced for the last 100 years, is antithetical to community self-determination. Which brings us back to Justice Funders’ call to action that philanthropy should be “redistributing all aspects of well-being, democratizing power, and shifting economic control to communities.” How can organized philanthropy, a byproduct of the extractive economy, undergo a Just Transition?

Resonance guides organizational self-reflection across seven elements: relationship to communities, leadership, operations, endowment, grantmaking strategy, grantmaking process, and grantmaking decisions. You can read the full Resonance framework here.

If we place the work of transforming philanthropy in the larger frame of transforming our economy, of fostering a Just Transition, the work is quickly recognizable as social change work. And, to that end, Resonance employs three fundamental changemaking strategies: confronting our history, changing our narratives, and reimagining our practices.

Confronting Our History

All change is contingent on understanding how we got where we are. Resonance includes a small poster-sized insert called “Stifled Generosity: How Philanthropy Has fueled the Accumulation & Privatization of Wealth.” At a glance, it guides the reader through historical milestones in US philanthropic policy: the establishment of tax-exempt status in 1913, the launching of the first donor-advised fund (DAF) in 1931, Congress’s decision in 1998 to allow donors to deduct the full market value of appreciated stock given to foundations. Seeing all the history in one place is revelatory and sobering. As the authors point out, public charities and foundations existed long before 1913, but with the creation of tax-exempt status, regardless of whatever positive intentions were in play, nonprofits and philanthropies became a field, a sector, a regulated part of the extractive economy. And, the authors posit, “This was the beginning of the non-profit industrial complex, in which the government has the ability to monitor and control social movements.” Indeed, in the 100 years since, the bulk of the nonprofit and philanthropic sector has done little to disrupt the very thing exacerbating the need for its work: the extractive economy.

Changing Narratives

Narrative change is now widely recognized as a critical strategy for changing hearts, minds, and policy. Rashad Robinson, executive director of Color of Change, recently wrote:

Narrative power is the ability to create leverage over those who set the incentives, rules, and norms that shape society and human behavior. It also means having the power to defeat the establishment of belief systems that oppose us, which would otherwise close down the very opportunities we need to open up to achieve real impact at the policy, politics, and cultural levels. Norms are powerful. Any challenge to norms, and any effort to forge new norms, must take a comprehensive approach.

So, what are the narratives about philanthropy that collude with the extractive economy? Resonance identifies two of the most powerful: charity and investment. “Charity as an institutionalized practice,” the authors write, “often perpetuates power dynamics between givers and receivers in which a small number of wealthy individuals and families aim to control and facilitate social change without tackling the root cause of inequity” (Resonance, p. 22). We need look no further than the simultaneity of Jeff Bezos’s protracted decision-making process on how to spend a tiny fraction of his wealth with the successful organizing that forced his company to abandon plans for a new headquarters in New York. It was a marked contrast in operating narratives about capital and what kinds are needed to strengthen communities.

Similarly, the authors argue, “investment” is absolutely essential to a Just Transition; we have to capitalize the development of myriad new green industries and businesses, for instance. But institutionalized philanthropy has adopted the extractive economy’s narrative about investment; namely, “the expectation of a maximum financial return to the ultimate benefit of the investor, at the expense of communities, and even the business itself” (Resonance, pp. 49–50). We see this manifest in how foundations invest their endowments (typically for maximum return), how much money they give away (typically the minimum required of five percent), and what kinds of organizations they fund. And perhaps most fundamentally, the investment narrative feeds the premise of perpetuity; most foundations invest and give money at a ratio designed to guarantee their permanence. The authors conclude, “These narratives and practices in our sector perpetuate the idea that the world’s biggest problems can be solved by wealthy people and institutions simply giving money away, without tackling the conditions that have allowed extreme wealth inequality to exist” (Resonance, p. 22).

Reimagining Practice

New narratives lead to new practices. If philanthropy were a force to catalyze a Just Transition, how would it do its work? Resonance delineates philanthropic practice on a continuum: more extractive, less extractive, restorative, and regenerative. For instance, in “more extractive” endowment management, funds are “invested in for-profit companies that cause social, economic and environmental devastation,” whereas in “regenerative” endowment management, funds are “invested in local and regional efforts that replenish community wealth and build community assets, like worker cooperatives and community land trusts.” Grantmaking practice shifts the primary accountability relationship from grantee to grantor, to grantee to community. In regenerative grantmaking practice, “grantmaking strategies are developed by movement leaders who are accountable to an organizing base (i.e. residents and community members)” (Resonance, p. 52). And grants themselves shift from one-year, restricted grants with idiosyncratic application and reporting requirements to long-term, general support as defined by movement leaders. Again, the regenerative practices all reflect and support community self-determination.

Vanessa Daniel, the executive director of a public grantmaking organization called the Groundswell Fund, articulates the centering of community members in philanthropy like this: “The people most impacted by injustice often see most clearly the path to justice for all people. Their leadership is critical to the success of movements on the ground and following their advice about how movements should be funded is critical to the success and relevance of philanthropy” (Resonance, p. 55).

What is relevant action in an economy producing the greatest inequality in modern times? What is relevant action when the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) tells us we have just 12 years to make the necessary changes to contain climate change to a manageable level? For philanthropy, the growing community of Justice Funders would argue, nothing less than a transformation of both premise and practice is what relevance will require.