April 25, 2019; Last Real Indians and Truthout

The “global crisis” of indigenous peoples being imprisoned and murdered because of their environmental activism isn’t new, but at an annual international gathering at the United Nations, leaders advocated for a large-scale campaign to spotlight these kinds of human rights abuses.

Writer Julie Mollins, of Germany’s Global Landscape Forum, reported from the 18th session of the UN Session of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in New York that the campaign would be run by and for indigenous peoples:

The new Global Campaign Against the Criminalization and Impunity of Indigenous Peoples will prevent, analyze, expose and reduce acts of criminalization and impunity….The campaign will also include human rights monitoring systems. Other activities will include calls to action, liaising with news media, networking and collaborating with non-governmental organizations.

As a number of indigenous leaders testified at the meeting last week, these widespread human rights violations are extinguishing indigenous rights to traditional lands across the globe.

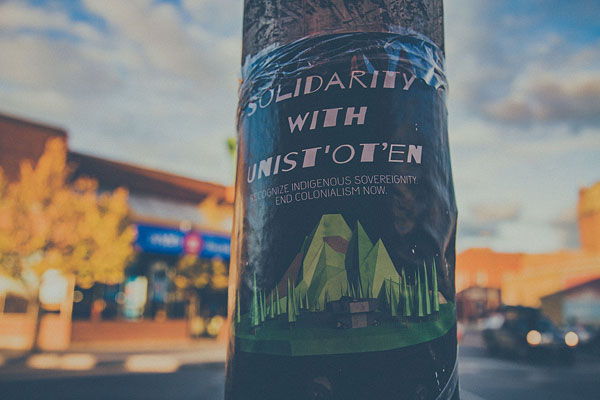

Freda Huson, of Unist’ot’en–Wet’suwet’en People of Canada, spoke about reoccupying her people’s land as a pipeline company bulldozed a forest and destroyed a heritage site. NPQ covered the standoff between the Mounties and the First Nations in British Columbia earlier this year, as well as the failure of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government to make progress on proposed protection of indigenous rights.

Huson addressed the forum:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

There are fewer and fewer animals to hunt, the salmon run is diminishing, and the water in the river is low. In order to protect what we have left, my family has been reoccupying one of our territories at Talbeetskwa which is along the Morice River in northern British Columbia. My ancestors have lived there since time immemorial, and I have been living there permanently for the last ten years.

[…]

They are trying to erase us from our own land. All these acts that continue are acts of genocide. They want to extinguish our rights to our lands. My people depend on our territory for berries, medicines, meat, and healing on the land. I am here today to make UN aware of the continued genocide happening in Canada, and to demand that our Indigenous rights and laws are respected.

Although details about funding of the campaign weren’t made clear, momentum toward increased collaboration across borders has grown as social media highlights protests like Standing Rock and communities elevate issues such as colonization, reparations, and land justice through education and advocacy. Indeed, as Turtle Island News, the weekly aboriginal newspaper of the Six Nations Grand River Territory, reports, indigenous peoples are making the case that protecting their land and resource rights also helps the fight against climate change worldwide.

But while it’s heartening to see some progress being made, perhaps more of the impetus should be on non-indigenous people to restore and preserve the land and resource rights of those who were here first. A simple place to start is by acknowledging the territory where you live, work, and play—there’s even an app for it created by a Canadian nonprofit called Native Land Digital—and considering what it means.

As Native Land Digital explains, “Territory acknowledgement is a way that people insert an awareness of Indigenous presence and land rights in everyday life. This is often done at the beginning of ceremonies, lectures, or any public event. It can be a subtle way to recognize the history of colonialism and a need for change in settler colonial societies… However, these acknowledgements can easily be a token gesture rather than a meaningful practice. All settlers, including recent arrivants, have a responsibility to consider what it means to acknowledge the history and legacy of colonialism. What are some of the privileges settlers enjoy today because of colonialism?”—Anna Berry