This is the sixth and final article in a series in which NPQ, in partnership with the First Nations Development Institute (First Nations), lifts up Native American voices to highlight issues concerning environmental justice in Indian Country and identify ways that philanthropy might more effectively support this work.

How can philanthropy support environmental justice and health among Native Hawaiians? A few key principles to keep in mind: 1) invest in indigenous leadership; 2) build community capacity and indigenous futures; 3) be a partner and friend, not just a funder; and 4) recognize how health is holistic and complex.

Author’s Note

This article was written prior to start of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The impact of epidemics is not new to indigenous peoples, and for this reason, these communities are currently experiencing the historical and contemporaneous traumas of an imminent health threat to their families. Infectious diseases have had lasting, adverse impacts on Hawaiians and Native peoples. For this reason, support from the philanthropic community becomes ever more critical. My prayers are with indigenous peoples and all communities around the world as we navigate this crisis, and my sincere hope is that we use this opportunity to reaffirm our commitment to a healthier world for us all.

The coast of Wai‘anae on the northwestern coast of the Island of O‘ahu is a stunningly beautiful landscape. With sweeping watersheds and vast valleys, it’s no wonder that Hawaiians settled and thrived in these traditional lands.

The area’s name itself, Wai‘anae, meaning “mullet water” reflected a healthy ecosystem where abundant forests fed nourishing streams that flowed into coastal waters teeming with marine resources, including the prized ‘anae, or mullet.

Wai‘anae was impacted early on by European contact. Its naturally rich uplands, once dense with ‘ili‘ahi, sandalwood trees, would be devastated by trade. Perennial streams fed by mountain forests were reduced to intermittent flows, harming traditional farmers who relied on streamflow and fishermen who relied on healthy coastal waters.

Today, the Wai‘anae coast is home to one of the largest concentrations of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in the world. Approximately 45,000 people live in this area of approximately 38,000 acres (close to 60 square miles). Of this 45,000, 60 percent are Hawaiian or from other Pacific Islands, compared to an average of 12 percent overall on O’ahu.

Wai‘anae is also home to some of Hawai‘i’s most toxic land uses. Both of the island’s landfills are located in Wai‘anae—one for municipal waste; one for construction waste. The island’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide, Kahe powerplant, is located in the area. Most recently, despite years of raising concerns about health issues in the community, both landfills are being expanded.

Repeatedly, Hawaiians and other indigenous Pacific Islanders have been placed in the position of being asked to tolerate the intolerable—namely, the systemic placement of toxic land uses in their ancestral lands and in their backyards.

What will it take to change this?

Native Hawaiians face injustices deeply rooted in systems that intentionally seek to marginalize and disenfranchise. One area where these injustices manifest themselves in particularly harmful and destructive ways is environmental racism. Environmental racism is found in practices and policies that result in the disproportionate placement of hazardous activities near indigenous communities and communities of color. As a result, these communities, who often already suffer from other forms of marginalization, are further affected by health afflictions.

For Native Hawaiians, the targeted placement of locally unwanted land uses in their communities is only the latest in a long continuum of colonial violence that has resulted in the devastating loss of native natural and cultural resources for centuries. Our entire post-contact histories are long tales of environmental atrocities.

In Hawai‘i, as elsewhere, the façade of colonialism has always been painted with benevolence, but it has also always been a very thin veneer poorly masking settler aspirations for power and control. Europeans, upon first arriving in the Hawaiian Islands in the late 18th century, made quick work of “settling in” our communities. The Gospel and the written word were served up symbiotically with Western capitalism, including desires for land ownership.

Within a century, weakened by foreign disease, the sovereign Hawaiian Kingdom would be forced to yield its authority to the United States under threat of armed conflict by a rogue faction of foreign businessmen who sought to exploit Hawaii’s natural resources for their own economic benefit. Our struggle to protect our homeland is centuries long.

Environmental justice is not only about modern racism. It is also about the long history of alienation from our homelands. As with many peoples’ ancestral lands, in Hawai‘i, the West colonized and seized the natural resources and lands previously controlled and stewarded by the Native Hawaiian people. This, too, is part of the way in which environmental injustice harms all of us. Once indigenous peoples are moved off their homelands, often by force, but also through the impacts of disease and war, Western settlers occupy these spaces. The short- and long-term results of these occupations have been the devastating exploitation of natural resources that has led to the current global environmental crisis.

Slowly, people are beginning to realize that indigenous ways of knowing and traditional ecological science offer essential tools for beginning to redress our dire environmental situation. To enhance these efforts, indigenous peoples must be empowered, and a Native way of seeing the natural world, one that views the earth as kin and not commodity, must be embraced.

We cannot undo the injustices of the past. We must do something about injustices today. Certainly, the acts of resistance being displayed on Maunakea or at Standing Rock reflect modern movements by Native peoples to respond to ongoing injustices. The crises we face are global and complex, so it may feel particularly daunting to identify ways in which to take small but powerful steps to become part of the solution.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Philanthropy is hard. On one hand, there is the drive for tangible, deliverable outcomes. On the other hand, there is the growing recognition that the systemic change needed to address some of the world’s most complex and challenging issues requires long-term investment in communities.

Yet, steps are identifiable, and, moreover, they are needed. Here are four critical steps philanthropic leaders can take to walk the long road to justice with indigenous peoples in Hawai‘i and elsewhere to bring health to their communities and support their futures.

1. Invest in Indigenous Leadership

Too often in Hawai‘i, “Hawaiian-serving” organizations are led by non-Hawaiians, actively denying Hawaiians these critical opportunities of self-determination and self-governance in their own communities. This repression of self-government in Hawaiian communities manifests itself repeatedly on environmental justice issues, as the land decisions that most severely harm Hawaiian communities are primarily made by non-Hawaiians.

Cultivating bona fide Native leadership builds community resilience. It builds economic resilience. It fosters education, and it empowers communities to both understand how to collectively redress environmental harm and innovate solutions that draw from ancestral epistemologies. It also actively fosters the ability of Native communities to protect themselves and their environmental resources.

Indigenous leadership is not about the exclusion of non-Native peoples from indigenous circles, but about actively creating space whereby community leaders have opportunity to amplify their voices in strata of power. Until this capacity is built, decision-making that harms the health of Hawaiians and other Native people will continue.

2. Build Community Capacity and Indigenous Futures

I worry deeply about the future of indigenous peoples. Collectively, we remain disproportionately impacted by poverty, environmental harm, and health ailments. Our youth as painfully overrepresented in the statistics on drug abuse and suicide. The unreported stories of youth and adolescent suicide in Native communities is a constant and stark reminder that mainstream media rarely concerns itself with the chronic crises faced by Native peoples.

Our nonprofit, ‘Āina Momona, founded by longtime activist Walter Ritte, remains largely focused on creating job opportunities and capacity building for Hawaiian youth. This is not simply because we believe in providing them jobs with livable wages, but we believe that providing jobs in the fields of natural and cultural resource management gives young people opportunities to partake in meaningful work in their own communities. We want all the young people we work with to know they are valued, and they have something incredible and unique to contribute to the world. We want them to have opportunities to find their passions and their gifts, and then have our support in utilizing those talents to create a healthier environment.

Meaningful work can change lives. Just as environmental racism alienated indigenous peoples from their homelands, conscious acts of compassion and justice can return Native peoples to their ancestral lands. This reconnection heals both people and places.

3. Be a Partner and Friend, not Just a Funder

There are many wonderful resources offering strategies for funding indigenous peoples. We should all work to continue to implement indigenous funding and decolonize philanthropy.

Yet Native peoples don’t just need funding; they need access and opportunities. To put it plainly, they need access to the privileges afforded to many people within the philanthropic community. They need access to the networks and accoutrements that funders often enjoy.

Much of the funding world is foreign to us. Only speaking for myself, I know that even the act of asking for funding is incredibly uncomfortable. This is not a reflection of the quality of the programs I represent, rather simply a reflection of the cultural environment in which I was raised. I’m getting better at it, but I have to work at it. Hard. I don’t know that I’ll ever be fully comfortable just asking for funding, but I also understand how incredibly important it is that I make these asks.

Hawaiian culture emphasizes humility. Rather than being direct and aggressive, we are taught that proper behavior is mindful, humble, and subtle. The gentleness of our culture admired by so many around the world is real and it runs deep. It often runs contrary to the directness that makes many fundraisers so successful.

Being able to dialogue through these cultural challenges and learning how to navigate through them is a critical need in the Hawaiian community. We have been blessed to have funders who have truly taken us under their wings to walk with us through these learning curves.

It’s these relationships that I have gained the most from, as a resilient friendship with a funder allows for being honest when I’m struggling, or if I am trying something anyway even when I’m insecure or unsure of myself. Having that relationship gives me the confidence to challenge myself in ways I would not with a funder with whom I do not have a personal relationship. It makes me a better administrator and funding recipient.

4. Recognize how health is holistic and complex

Achieving environmental justice demands more than just stopping the placement of toxic sites or removing hazardous land uses. It is about restoring and maintaining ancestral places and practices. It is about repairing the essential connections between Native peoples and the natural resources to which they trace their genealogies. Many indigenous cosmologies originate with the earth itself, because these peoples have long understood and respected that the earth itself is the source of life for us all. For example, in the Native Hawaiian belief system, Hawaiians are the living progeny of Wākea (Sky Father) and Papahānaumoku (Earth Mother). The islands, elements, food crops, and humans are the descendants of their union. Many of the uprisings in the Hawaiian community, like Maunakea or the protection of traditional food crops, are reflective of the deep responsibility Hawaiians feel to care for the resources that are part of this kinship.

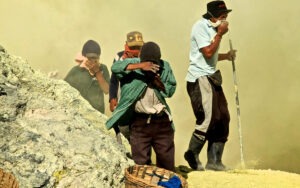

To harm the earth is to harm all of us. Therefore, in this regard, Native communities affected by environmental racism are the global canaries in the coalmines. We are sentinel peoples—indicators of afflictions that will befall us all if we do not change course.

The historical trauma carried by Native communities is intergenerational; therefore, it will take generations to begin to undo the lasting damage. The investments in indigenous communities must be long-term if they are to help heal pain that exists across generations and throughout numerous facets of the community.

The Road Ahead

Despite the trauma and injustice, I am rich with confidence in the Hawaiian people and indigenous peoples throughout the world. I know they are my brothers and sisters, and I know their struggles are my struggles. I know their healing will be my healing.

It is a long road ahead. It will often be a dark road riddled with great uncertainty. Hawaiians have a saying, “I ka wā ma mua, ka wā ma hope.” The future is found in the past. Therefore, in the absence of a clearly lit path, we must hold fast to our faith. We must remember that the spirit does not forget and that the past, rich with the many who came before us, will always guide our way forward.