March 14, 2016; KELO-TV (Sioux Falls, SD)

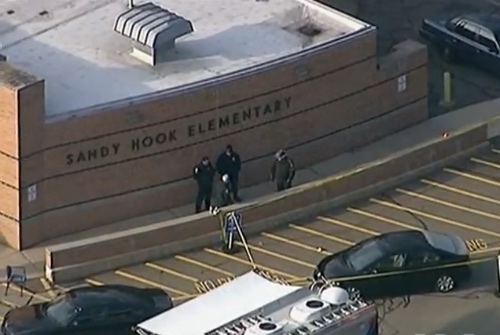

In 2013, NPQ reported on South Dakota’s decision to allow school district staff or volunteers to be armed while performing their duties. The “school sentinel” bill was enacted in response to the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut and other cases of gun violence on school grounds. No school districts chose to implement the law—until now.

Tri-Valley School District, about 10 miles north of Sioux Falls, has a population of about 5,500 and teaches just over 800 students. Despite its proximity to the state’s largest city, it has no local police force or school patrols. There is a sheriff’s deputy that acts as a school resource officer “most of the time,” according to district officials. In the event of trouble, the school does have a lockdown “panic button,” but officials fear county law enforcement would not be able to respond in force in a timely manner to protect students and staff. Fears of school violence and previous planning steps have led the school board to provisionally approve a school sentinel program as the next step in what is hoped to be providing a safer campus.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

If given final approval next month (as currently appears likely), the district’s school sentinel policy would require individuals to apply, undergo psychological evaluation, secure a concealed weapons permit, and complete state law enforcement training. The final step is approval by the school board.

Three aspects of the proposed policy are unsettling. First, the identities of Tri-Valley’s school sentinels will be kept secret. The superintendent and school board will know, but the public will not. It’s not clear whether even the building principal and staff will know who is authorized to be armed on campus. Second, the weapon used by the school sentinel will likely be in a locked cabinet, not with the person. While this might sound safer than carrying a weapon when among students, it means that quick reaction to threat situations—the purpose of the policy—might not be possible. Third, while discussion surrounding the policy assumes the sentinel or sentinels will be employees, the policy itself refers only to “individuals,” leaving open the possibility of volunteers being authorized.

We understand the desire to keep children safe, but is this the best way? Imagine a nightmare scenario where one or more armed people storm the school. Staff see one person—staff or school volunteer—scrambling to get to wherever their weapon is locked up, apparently not following procedure by sheltering in place or protecting students in their classroom. They may not even be able to access their weapon, depending on where the shooters are located and how the anticipated school lockdown protocol works. Assuming the sentinel is able to retrieve the weapon, the sentinel attempts to defend the staff and students, who don’t immediately know the sentinel’s identity and only see a person in street clothes with a gun in their school during a shootout, hostage situation, or similar tragedy in progress. When law enforcement arrive on the scene, they also will likely not be immediately aware of the sentinel’s identity. Even if the superintendent is able to communicate with law enforcement, communication takes time and, besides, law enforcement protocols tend not to distinguish between armed civilians at a crime scene.

The district superintendent has sent a letter to parents about the proposed policy. The school board has not yet heard public input yet, but it may well hear concerns before it takes final action.—Michael Wyland