September 25, 2018; CityLab

Readers will likely remember the “broken windows” era of policing, first introduced by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling and later adopted in practice by New York Major Rudy Giuliani and police commissioner Bill Bratton, who touted it as a model. The theory, which held that when police and city officials pursued even the smallest of indicators of neighborhood decay, like broken windows or littering, the more serious infractions of law would also be reduced, took hold when it was given credit for lowering the crime rate in New York.

These claims were debunked after the discovery that the drop in crime was nationwide, not limited to New York, and could easily have been associated with the 39 percent drop in the unemployment rate in New York. Also, eventually, the theory mutated into something more onerous and the broken windows policy came under great criticism for criminalizing poverty and ushering in the “stop-and-frisk era,” which had the effect of further alienating the police from many low-income communities. Readers may similarly remember campaigns against “squeegee men” and subway fare evaders, among other types of allegedly antisocial behavior.

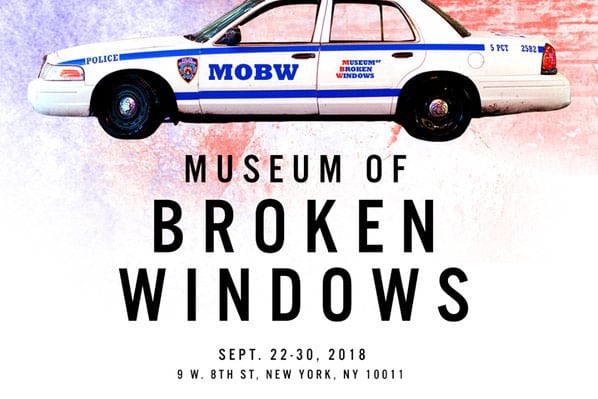

Now, the New York Civil Liberties Union is calling attention to the still-active and destructive remnants of these policies through the Greenwich Village–based, pop-up Museum of Broken Windows. Featuring performances, installations, and other contributions by activist artists, the museum is designed to call attention to the continued “ineffectiveness of broken windows policing, which criminalizes our most vulnerable communities.” It also emphasizes the racial injustices that provide context and characterize the outcomes of those policies. As Laura Feinstein writes for CityLab:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In addition to original art, the museum is filled with heartbreaking mementos, press clippings, and photos from the height of broken windows. It has the haunted time-capsule feeling of the 9/11 Memorial Museum and the physical look of an activist meet-up space. Splashed on the walls is beat-esque poetry graffiti. Statistics illuminate police brutality rates and highlight racial inequality in the criminal justice system. This stands shoulder-to-shoulder with large-scale installations that speak directly to broken windows as well as the period in 2011, when stop and frisk was at its height.

One of the most striking pieces in the show is Jordan J. Weber’s installation of a destroyed cop car. The cruiser’s windows are broken, and ferns, peace lilies, and other plants grow through the doors and windshield. The plants were chosen specifically for their ability to purify air, as an homage to NASA’s Clean Air Study and a direct reference to Eric Garner’s last words—“I can’t breathe”—as he was asphyxiated by Staten Island police in 2014.

The exhibit evolved out of a larger effort called “The Listening Room,” which travelled through 30 neighborhoods and parks in New York City soliciting stories from thousands of people about their experiences with the police and for policy ideas, which were then sent to the mayor.

By offering a 50-year retrospective, the Museum of Broken Windows hopes to show just how deeply this one idea affected the city and countless lives within it. “We believe this did not start with Giuliani and did not end with Giuliani,” says Daveen Trentman, executive producer of the museum. “We wanted to work with artists who were directly impacted, artists who were formerly incarcerated, and had profound experiences of being impacted by these policing practices.”—Ruth McCambridge