Anasa Troutman wears many hats (including being a record producer), but in this interview, the focus is on her role as executive director of Historic Clayborn Temple, a $25 million project to restore a building that was the central organizing hub of the 1968 sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis. On April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated while visiting Memphis to support that strike.

The interview that follows explores the history of the Clayborn Temple, the project to restore it, and the vision of Troutman and her colleagues to use the temple as a hub for developing a community-based economy in Memphis that is Black-owned, Black-governed, and which sustains a thriving culture rooted in the Black imagination.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Steve Dubb: You once said at a conference that Memphis was the “most hopeful and creative place” you know. Why is that?

Anasa Troutman: The thing that is so inspiring to me in Memphis is the sense of innovation and creativity: W.C. Handy, Ida B. Wells, Robert Church, Stax, the Blues Highway. Memphis is the home to so many cultural innovations that have come out of the minds of Black folks and the Black imagination.

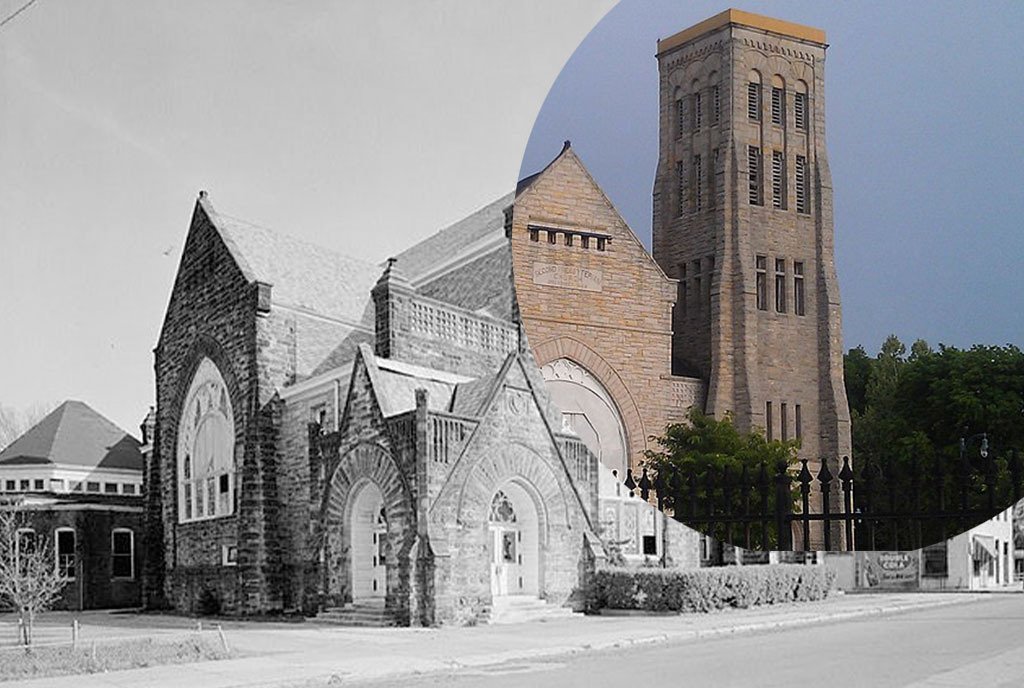

SD: What is the Historic Clayborn Temple, and what does the renovation project, which I understand to be a $25 million project, involve?

AT: Historic Clayborn Temple is a lot of things, but it is best known for being the headquarters of the sanitation workers’ strike of 1968. The reason why that strike was so important is because it was, at its core, about sanitation workers being able to have a union to protect their rights.

In the broader sense, it was really about the fact that these men had been abused for so long, working under terrible conditions. There were little things. Back then, there were no trash bags, so sanitation workers literally dumped people’s garbage bags into a bin that they purchased themselves and which would erode over time. They would get trash and maggots and trash juice on their clothes and not have a place to shower or a uniform, so [they] could keep [their] clothes clean. These are the little things that eat away at your humanity.

And then the big things, like they would be sent home if it rained, cutting their wages more. And the dangerous things. What led to the strike in the first place was the fact that two workers were killed in the back of a truck. The range of things they had to endure as human beings, from small things to life-and-death things were for them why they went on strike.

Our hope and our vision for the building is that it will be a place of gathering and a place of story but also…a place for intersectional conversation.It became a national conversation because it coincided with the conversation that [Martin Luther] King was having about his work and about the future of the Civil Rights movement. King was having a hard time convincing his friends, supporters, and funders about the merits of having a multiracial movement around poverty. He was like: “In Memphis, they are doing this work. They are having a conversation specifically about race, about class—if we can go there and help to make this successful, that is the exemplar we are looking for to make the case for the Poor People’s Campaign.” It is well-known because not only did King come here to be able to join a movement, but also, unfortunately, this was the place where he was assassinated, and the reason why he was in town when he was assassinated is because he was working with these families.

So, this building is holding the memory and thoughts of this strike, holding the grief of this community as they had to reckon with the fact that King was here when he was murdered, and it also was an AME [African Methodist Episcopal] church since 1949, holding like 50 years of folks coming into a space. And so, this is also holding 50 years of memories of this community.

Beyond that, the building was built in 1891. It was once an all-White Presbyterian church, so it is also holding the tension of the protests and sit-ins of younger White teenagers who were going to church there, who were like, “We want to have our Black friends come to worship with us,” and the teenagers who were outside trying to get in to worship, and the elders who were standing outside and locking them out. This building is holding all those things. It really, for me, is like an actual embodied symbol of the struggle at the intersection of race and class in a city that is sitting at the intersection of race and class in a country that is sitting at that intersection.

Clayborn is that space for us. We are reopening in two years as a cultural arts center. So, we will be primarily a space for gathering, primarily a space for storytelling. And we will have a second building on the back that will be dedicated to restorative economics to continue the work of the sanitation workers. Because we are inspired by their story, but their story must not end with them. We need to take up the mantle and do the work. Our hope and our vision for the building is that it will be a place of gathering and a place of story but also…a place for intersectional conversation about what it means for all of us to experience our abundance and be safe in our communities.

SD: At a conference you compared your work at Clayborn to being a record company owner. You said: “I don’t need to know historic preservation; I need to know how to hire architects and construction teams. I know how to impart vision, build a team, and build community. If you have that, you can do anything.” Could you elaborate on this theme?

AT: I believe that with my whole heart. My first career was as a producer. I began at 19 or 20. I have lived a life doing things that I don’t know how to do. In school, I was pre-med in biology. But I ended up being a producer and record label owner. None of that was planned. I followed the spirit.

And because my first following was being a producer, I understand how to do things that you don’t know how to do. It’s powerful to be able to sit in the center and hold the vision and understand what is required of you to be able to execute that vision. Also, it’s a very beautiful exercise in community building because what I know is I can’t do anything by myself. I can’t depend on myself to manifest a dream. I need to have people in the room who can see the vision with me but also understand the mechanics of making that vision come true.

When I moved to Memphis, and the new surprise of my life was I was going to become a historic preservationist and developer for a major spiritual-cultural asset in the community, my nervousness wasn’t about if I could pull it off. My nervousness was about whether I would behave in a way that I was worthy to be able to be the steward of this building—whether I would be able to build the community around me and learn its lessons, so I could become a part of the community in a meaningful way.

SD: Where were you from originally?

AT: I was born in Manhattan. I spent my childhood in Jersey, then Charleston, and then back in Jersey until I went to college. I went to college in Atlanta. I moved back to the South when I was 19 years old. When I left Charleston—I guess I was nine years old—I never felt comfortable outside of the South again.

I feel like my calling is to work specifically in the South. Because this is the beginning of our wounding as a people and as a country. I don’t want to be dramatic, but I feel it is my destiny to be in that space and help heal those wounds. There are many of us who are here doing that work.

This is basic psychology. If you have a trigger or a wound, you have an emotional dis-ease in your body. To heal, you need to understand your childhood and where that wounding came from. If America is going to be a place of freedom and liberation for all people, then we need to go back to the original wounds. We need to be able to say we’re going to open this wound and clean it out and put a bandage over it and let it out again and see what happens.

That is how healing works. There is a Rumi poem I quote all the time that says the wound is where the light enters you. I feel like that about my work in the South and particularly in Memphis. The hardest places, the bloodiest places, the most wounded places are the places where those of us taking that work up need to go.

SD: At NPQ, we have long been interested in governance—how community groups make democratic decisions—and management, how you implement them. Could you talk more about what it means to approach community development as a producer and how that might lead you to approach the work differently?

AT: I think fundamentally, the difference is that I’m not an administrator. Governance is not my expertise. My expertise is creativity and imagination.

My approach is never with an answer. It is always with a curiosity. I’m never coming in: “Here’s how it’s going down.” I’m walking in: “What do we need to do to accomplish our goals?” Which is most often not a thing but a way of being.

When I think about our organization or Clayborn or the Big We, we talk about our mission as being about building beloved community. We are not talking about whether we need to serve this many people doing this many things. We talk about: How do we show up for each other in community? How do we show up for more and more people? How do we do that in a more embodied way?

And then I think, beyond that, when you’re a producer, once you satisfy your curiosity, your goal becomes completion. You’re like, “Okay. How many sessions do we need to do to get this song done? How many pages need to be completed for the script to be done?” It is all about mechanics. But it’s about mechanics in service to the creative vision.

You must be able to convey the vision to the people who are doing the mechanics in such a way that they can contribute to the vision. Your sound engineer could come in and do what they do, but you have to say no, we want this song to feel bright and summery like you’re falling in love. That affects the way they do their sound engineering. Or, we say that this audiobook is serious—it needs to be heavy and girthy and carry this weight of importance. And they produce differently.

Being able to help people align around your answer to your curiosity in a way that allows them to execute their mechanics in an expert way—that, to me, is the beauty of producing.

SD: How is the project structured to be community-governed and return profits to the community?

AT: The first thing we did when we started our board and were thinking about governance was that we only invited people who were connected to the story of the building in some meaningful way—actual physical neighbors, folks who had preached in the building, folks who had gone to church in the building, family members of sanitation workers, and the like.

I specifically left off people with wealth unless they were connected to the building, like the guy who was a contractor. Unless they were specifically connected to the building, they were not allowed to be on the board because we wanted for the core ethos of the organization to be authentic to the people whose story it was.

We cannot just be out here talking about racial justice without talking about economic justice and without talking about Black abundance.Then, we built out a community leadership council. We have a whole program at Historic Clayborn Temple, our community program that is building a community of folks who have shared language and practice in restorative economics and who have ancestral grounding in historically Black neighborhoods—not just our neighborhood in South City or in Soulsville, but White Haven, Orange Mound, and other neighborhoods where the sanitation workers lived.

As we continue to grow, the intention is for Clayborn [to] become a membership-based organization. Not governed by a group of folks who have big checkbooks. But governed by the community and having decisions made by that community.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In addition, there is a plan for a second building, called the Crenshaw-Jones Center at Historic Clayborn Temple, and in that building the programming will be about creating space for learning for community members who want to participate in restorative economics. Whether it is because they are in the co-op accelerator or because they are going through the curriculum or because they are being invested in by our foundation or Big We capital, the entire “Big We” system was built around the idea that the work at Clayborn Temple could not just be about restoring the building, it had to be about restoring the community.

We know we need to talk about the economy. We cannot just be out here talking about racial justice without talking about economic justice and without talking about Black abundance. So, yes, Clayborn is a place of learning, storytelling, community building, and relationship. And we also need to be able to give grants and invest and bring new money into the city.

And yes, we have a way to think through what governance looks like not just in the building but on a neighborhood scale. If we restore Clayborn and not the neighborhood, we’ve failed. Sanitation workers aren’t out there saying, “Save Clayborn Temple.” They say, “Help us save our lives.” If we only think about the physical structure and not about our ancestors, then we failed them. And we are just not going to do that.

SD: You used the word membership. Does that mean people making an investment? Is there a cost to membership?

AT: Not right now. So, this is in process. Eventually, we will have a membership structure. I don’t think the membership for Clayborn will be a cost. But when we talk about membership for larger investments, there will be a cost. Some folks will pay their own way. For some people, we will pay their way for them with the money we have raised. The whole point of this is to figure out how to flatten the access. I don’t want somebody’s grandma to be like, “I can’t invest in this neighborhood because I don’t have the $50 a month or $1,200 to buy in,” so maybe we have it for her, so she can still participate without having access to the money up front.

SD: The money itself, where is it coming from?

AT: For the building, our hope and prayers are that it will be all philanthropy. The ecosystem of projects will require a much larger swath of money. There, we will need a mix of philanthropy and investment, but the $25 million investment in the building will be 100 percent philanthropy.

SD: Is there any money coming from the city of Memphis or Shelby County?

AT: Our first big grant was from Shelby County right off the bat. In the city, we have a partner because [in] phase two all our National Park Service grants were…in partnership with [the] city. We are also supported by two foundations in the city—the Assisi Foundation and the Hyde Foundation. Outside of that, all our fundraising is done outside of the city.

SD: Could you talk about some of the ecosystem-related projects like the Southern Shift Initiative and the Memphis Futures Fund?

The vision is to help Memphis become a city of a future that is Black-owned and Black-governed.

AT: The Southern Shift Initiative is really thinking about how we approach from a strategic standpoint shifting the cultural economy in the South. We started with a cohort of creatives—filmmakers, actors, visual artists, musicians—who are thinking very deeply about the future of the city, who are starting their own businesses, who are buying or developing land. We invited them into a cohort, and they have been working together for the past year to really reimagine what their relationship with each other and the city is and how, if we were to bring in investment, they would spend that money.

The Memphis Futures Fund is really thinking about this neighborhood, our neighborhood in South Memphis, with Clayborn as a cultural anchor—what would it look like for us to be able to come in and coalesce investors around the development of the neighborhood through the lens of Black imagination?

So, we’re not talking to traditional developers. This vision is built from the inside out—projects from the community, financing that is community-focused and community-directed. The vision is to help Memphis become a city of a future that is Black-owned and Black-governed.

SD: How much of a connection do you have with Highlander, the civil rights school in eastern Tennessee?

AT: Much of what I know and believe I learned at Highlander. I worked at Highlander for three years. In 2007, I produced the 75th-anniversary celebration at Highlander. My first six months at Highlander, I literally had to sit at the feet of the civil rights elders and learn all the stories from them and understand the mechanics from them.

Highlander is very much part of my movement DNA. One of my biggest teachers was Hollis Watkins Muhammad, a brilliant cultural strategist. And I was mentored for six months by Bernice Johnson Reagon. The mechanics of cultural strategy and the intentional leveraging of song and music—all those things I learned at Highlander.

SD: What does the term “restorative economics” mean to you?

AT: Restorative economics: we learned that through our partnership with Nwamaka Agbo. Nwamaka and I were both fellows at [the] Movement Strategy Center.

The reason why I was attracted to the work on restorative economics in the beginning was because when I was in conversations about King, sanitation workers, Robert Church, the need to restore the visions of our ancestors, I started calling the work at Clayborn Temple “restorative development” to couch for folks in Memphis that we were not talking about traditional speculative real estate development, but rather something else. I just coined this phrase because I wanted people to understand that I was talking about something different.

And then, when I reconnected with Nwamaka and I learned about what she was calling restorative economics, it clicked for me. What I love about restorative economics is that it is such a human-centered approach to the economy. It is such a heart-centered, generous, loving, and caring approach to the economy.

And it starts with telling the truth. Restorative economics doesn’t exist without storytelling. It starts with you sitting down face to face and talking about what is. Not what you wish it was. Not what you don’t want to feel guilty about. What is the truth about this neighborhood, this system, this world, our interaction, our ancestors’ interaction? And it allows you to build on an economic framework that has our humanity and our hearts at the center. Capitalism does not account for our humanity.

That, to me, is what restorative economics is about. It is about being able to construct an economy that allows space for people to have joy—everybody to have joy. Because as we know, abundance for a few people is not abundance. That is still scarcity. Joy for a few people is not joy. Love for a few people is not love. Those things do not exist unless everybody has access to them—not in a real way, not in a spiritual way.

SD: What does it mean to you to operate out of a mindset of abundance?

AT: My relationship with abundance is interesting because I didn’t have a relationship with abundance before. My intentional cultivation of a mindset of abundance coincided with my building of a relationship with Memphis and Clayborn Temple.

For me, true abundance is about people exercising their right to have and do and experience the things they want. Not everyone wants to have a garden. But if you want one, I want you to have that. I am not saying everybody should have everything. Because, of course, we need to think about boundaries, about access, about [avoiding] harming other people.

But if we can have a conversation about what enough is—and within that container of enough-ness, you can have and be and go and feel whatever it is you need to, in your human experience, that to me is true abundance.

But it is difficult to have a conversation about enough-ness when we live in a culture of scarcity. Because when you believe that things will run out, nothing is enough. You are always grabbing for more.

The most important thing in this work as folks who are thinking about the future of humanity in a meaningful way is to tend to our emotional and spiritual health. Because the complexity that we need to achieve as human beings about abundance requires that we are whole, requires that we are healed, and requires that we are aware of ourselves—and our shortcomings, triggers, and emotional barriers. We need to navigate these things in a healthy and beautiful way to get to the place where everybody can experience their abundance.

SD: Anything else that you want to add?

AT: What comes to mind are the stained-glass windows. It is important because it shows how we are doing everything we can to infuse the stories of these people and families into every part of the restoration of this building. Yes, we will have a museum. Yes, we will [have] a resource library. But also, their stories are in the windows. Their stores are in the stone. Their stories are in the plaza.

The reason why we did not put Martin Luther King in the window, but instead put in T.O. Jones, Larry Payne, and Cornelia Crenshaw is because we want people to relate to those faces. “Oh, that’s my auntie. Oh, that’s my cousin. Oh, that’s my brother. Oh, that’s me.”

That is why Clayborn Temple is so meaningful to me. It is a reminder to everyday people of their power to transform communities.