July 14, 2020; Gothamist

“You know how it feels to look at the same detectives who couldn’t figure out who killed your children’s father, and now you’re putting your son, the same delicate situation, in their hands?”

These are some of the raw emotions felt by LaToya Jack, mother of Lamar Gibson, who was killed on Monday July 13th in East Harlem. Lamar’s mother LaToya is referring to the unsolved murder of Lamar’s father on the same block nearly 10 years ago.

This tragic loss of life and of intergenerational and community trauma through gun violence has gained national attention during a summer of blistering heat, racial reckoning, and rising COVID-19 cases.

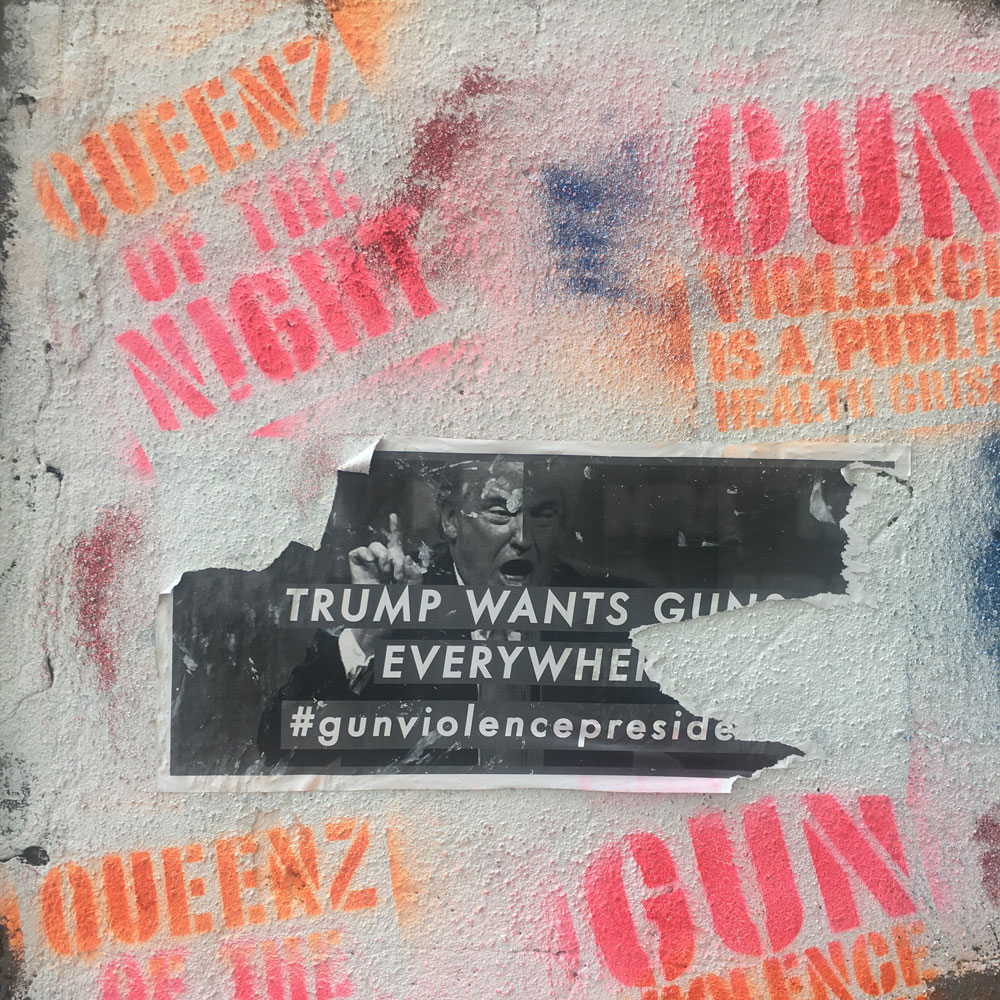

These complex problems are without a doubt exacerbated with a president advocating for federal law enforcement to enter various cities, which has resulted in recent protest escalations, law enforcement violence, and civil rights abuses recently seen in Portland, Oregon.

Current research by the University of Pennsylvania has focused on crime trends during COVID-19 for over 25 major cities. Although some cities have seen a drop in the overall crime rate of more than 30 percent during the pandemic, others have experienced rises in homicides and shootings. Shootings within New York City increased by 130 percent in comparison to 2019. Even with a steep decline in homicides since 1990, New York has experienced 400-plus shootings in the first half of the year, which is the highest since 2016. By July 2nd in Chicago, 336 people had lost their lives, with many concerned the city will match the 778 deaths level experienced in 2016. Philadelphia experienced more than 20 people injured during 4th of July weekend shootings, with seven people losing their lives.

The murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery are tragic indicators of a larger systemic failures around racism, policing, justice, and public safety. These recent loses of life to gun violence further displays failures within the “ecosystem of public safety.” This is occurring in tandem with massive protests focused on US policing, systemic racism, and white supremacy.

The question of how to address these upticks in violence while national movements call for police restructuring, defunding, or abolition has been met with a multitude of perspectives. Some have argued of a “Ferguson Effect,” where national attention of police violence instills trepidation onto officers in the field and even empowerment among offenders. The evidence is unclear to support that theory; even though crimes occurred after protests in cities like Ferguson and Baltimore, there is a clear need for more research. For instance, New York cited no changes in crime rates during the period of 2014 where it slowed down the racially problematic and aggressive stop-and-frisk tactics.

National unrest around racialized police violence is not new, and neither are increases in gun violence during the summer months. Rises in summer crime are often attributed to the warmer weather drawing more people out, which is currently compounded by the months COVID-19 further deepened persistent issues tied to inter-community violence such as unemployment and uneven access to supportive services, housing, hunger, healthcare, and more.

Many cities in which violence has increased have been disproportionally affected by COVID-19, with higher rates of infection, death, and unemployment rising from 28 to 35 percent, as seen in some neighborhoods in Chicago. These social, economic, and health disparities put overburdening pressure onto systems, people, and organizations who focus on violent crime and community well-being. “Because this is not one crisis, this is two crises operating at the same time, this could in fact be worse than what we saw in 2016,” stated Thomas Abt, a senior fellow at the nonprofit Council on Criminal Justice.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Yet, for organizations, communities, and individuals engaged in violence interruption work, such as Cure Violence, Save our Streets, and Man Up!, this storm has been on the horizon for some time.

“We should have anticipated this,” says New York City’s public advocate Jumaane Williams. “Everything in these communities has been made worse by the pandemic, everything. Why did you think gun violence [would] be different?”

Many of these groups work to curtail police involvement and the factors exacerbating local conflict. They mediate conflicts between individuals or local groups and connect people to educational and employment resources and mental health services. There are a variety of methodologies, such as Temple University Hospital’s trauma department’s program Cradle to Grave program engaging in bystander first aid training and victim support, as well as free gun locks within the community.

A growing body of research supports gun violence drops in areas of New York City with these programs in place—some as much as 50 percent. Further national findings on community-centered efforts found a nine-percent drop in the murder rate, with 10 organizations per 100,000 residents. Patrick Sharkey, sociologist and author of Uneasy Peace, notes these organizations’ impactful and underappreciated role in public safety: “The model that we’ve relied on to control violence for a long time has broken down. This gives us a model. It gives us another set of actors who can play a larger role.”

Many advocates and organizations have highlighted gun violence of this nature as one of the most frequently ignored public health epidemics. Since 1968, more Americans have died from gun violence than in battle during any of the wars fought since the nation’s inception, yet smoking and seatbelts have been more accessibly treated as public health problems.

Efforts to treat gun violence as a public health matter received a major setback when Congress in 1996 forbade the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from using money to “advocate or promote gun control.” Today, however, legislators such as Representatives Rashida Tlaib (D-MN) and Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) are promoting programs through the “Breathe Act” that uplift violence interruption programs and treat violent crime as a public health matter.

Recently, more than 50 US cities and counties, along with hospitals, and school districts, have declared racism as a public health crisis, yet there are questions as to what these statements will develop into. But as COVID-19 has demonstrated, a public health approach saves lives—just as not doing so costs lives.

Pastor Gil Monrose, an anti-gun violence activist in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, envisions a strategy akin to the one New York City has used to address the pandemic:

Just like we have a plan for COVID-19, we’re moving in phases, and every department moving, we need a specific plan, specifically for violence on a federal level, the state level, the city level—[a] multifaceted approach of non-profit organizations, clergy-led groups, and gun violence interrupters.

“We can’t continue to work in different silos,” says Monrose. “We must have a full plan for New York City.”—Chris Cannito