October 7, 2015; Common Dreams

It’s old news, so to speak, about Christopher Columbus. The Genoese explorer received his commission and subsidy from the Spanish monarchs who also brought the Inquisition to Castile and Aragón—as well as to Spanish possessions ranging from the Netherlands and Naples, the Canary Islands, and after Columbus, the Americas as well. As a result of his explorations of the new world, nations of Native Americans were slaughtered with impunity, wiped out, erased from their lands.

Bill Bigelow, the curriculum editor of Rethinking Schools and the co-director of the much admired Zinn Education Project, writes on Common Dreams about the greater heritage of Columbus’s voyages—the introduction of the trans-Atlantic slave trade as well as the unleashing of “complete genocide” on the Taínos he encountered in the “New World.” He also notes the relatively consistent manner of presentation Columbus gets in American history books that recounts his enslavement and killing of Taínos in a manner that can do nothing but lead children to think that the lives of the Taínos didn’t—or don’t—matter.

“Enough already,” Bigelow writes. “Especially now, when the Black Lives Matter movement prompts us to look deeply into each nook and cranny of social life to ask whether our practices affirm the worth of every human being, it’s time to rethink Columbus, and to abandon the holiday that celebrates his crimes.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Some localities—and one state—have turned against honoring Columbus, given his destructive agenda and accomplishments. Back in 1990, South Dakota renamed Columbus Day “Native Americans Day,” and now nine cities including St. Paul, Albuquerque, Seattle, Minneapolis, Anadarko (OK), Portland (OR), and Olympia (WA) have also joined in the official shift in attitude toward Columbus versus Native Americans. Berkeley, California, may well have been the first to make the switch to Indigenous People’s Day back in 1992.

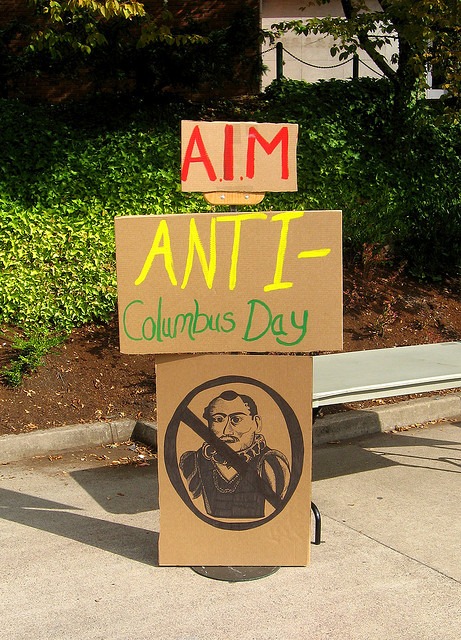

Columbus Day itself is a product of civic activism. The first official Columbus Day was in Colorado, where in 1905 an Italian immigrant named Angelo Noce got the governor to put Columbus Day on the calendar as a holiday to honor, as the governor’s proclamation read, “the patriotic Americanism of the Colorado Italians whose generosity prompts them to present to the state an emblem of appreciation of the services to mankind of one of their countrymen, and a material evidence of the good citizenship of those Americans who belong to the same race as he did.” In recent decades, the activism has gone the other way, most notably when American Indian Movement activists poured fake blood on a statue of Columbus in Denver in 1989. On Monday, October 12th, activists used fake blood to paint a red line down the parade route in New York City, and 500 protesters lined the route beating tom-toms and chanting anti-Columbus slogans; police arrested at least 147 of the protesters on misdemeanor charges.

By most historical accounts, Columbus doesn’t qualify as someone to honor for his contributions to America. There are many other Italian-Americans who have made major contributions to the creation of the good parts of our nation, to the democracy that this nation aspires to be, such as Fiorello La Guardia, the mayor of New York and a Republican supporter of FDR’s New Deal; John Sirica, the judge who oversaw the Watergate hearings; and Monsignor Geno Baroni, the founder and first president of the National Italian American Foundation, the founder of the National Center for Urban Ethnic Affairs, and the Catholic coordinator of Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Further, consider those Italian-Americans whose contributions came at the cost of their lives, such as George Moscone, the mayor of San Francisco who was assassinated by Dan White just before White killed Harvey Milk; and Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, the two anarchists who were wrongly convicted and executed, victims of the intersection of anti-Italian prejudice and the Red Scare hysteria of the early 1920s.

Given the revelations of history, our nation can do much better than honoring Columbus. We can divest from Columbus, yet we can honor the contributions of Italian-Americans whose civic contributions invested in the best of our nation today and simultaneously recognize and the Native Americans whose society and lives suffered directly and intentionally due to Columbus, Ferdinand, and Isabella.

“We don’t have to wait for the federal government to transform Columbus Day into something more decent,” Bigelow writes. “Just as the climate justice movement is doing with fossil fuels, we can organize our communities and our schools to divest from Columbus. And that would be something to celebrate.”—Rick Cohen