From the beginning of time, perhaps from the moment Cain killed his brother Abel, humans have been grappling with the issue of violence. For some, the word refers singularly to the harming of physical human bodies, including all forms of assault and murder. For others, namely those who were upset at the uprisings of the summer of 2020, destruction of property can also be considered “violence.”

And while most people will generally agree that violence is bad, few will admit their perception of violence is highly circumstantial. When police commit violent acts, it is labeled as “use of force.” When soldiers massacre the citizens of remote countries, it is seen as a necessary evil for the sake of “democracy.” While the irony may be easy to spot in those examples, when it comes to how we regard the violence in urban communities, there are certain nuances that fly under the radar.

Whatever the term—community violence, urban violence, inner-city violence, or the officially dethroned “Black-on-Black crime”—the image conjured is the same. The polite/liberal/political jargon beckons you to picture a poor, mostly Black or Brown neighborhoods where young men are the perpetrators of heinous crimes. This is the manifestation of violence society is most concerned about, and the type that state-perpetrated violence supposedly counteracts. However, if we take some time to dig deeper, we would find that terms like these are indicative of a flawed approach to the problems plaguing underserved populations.

Recently, I had the pleasure of speaking with a bright young colleague who has been spearheading a research project commissioned by a particular nonprofit in the field of criminal justice reform. The project was a survey of the trauma experienced by survivors of “community violence” and the process of how they dealt with that trauma.

The definition at the top of their survey was:

Community violence is harm that happens in a community or neighborhood that impacts individuals and groups of people.

If a respondent indicated they had indeed experienced “community violence,” they were eligible to complete the survey. The pool of respondents consisted of participants from “community-based” nonprofits that focused on violence in some way, meaning the respondents were predominantly Black.

I told her that their definition was both broad and specific, at the same time, and asked what she thought I meant by that.

We identified that the word harm is vague, impact is vague, and community violence is all-encompassing, yet we both understood what exactly the definition meant to say.

You see, community violence could be interpreted by a respondent as domestic violence, sexual assault, or violence done by police, among other things. Harm that happens in a neighborhood and impacts people could refer to physical assault, but it could also refer to systemic oppression. At absolutely no point in the entire survey was the definition further clarified to mean what it really meant: Have you as a Black person experienced physical harm inflicted by another Black person who was not an intimate partner or a policeman, the harm being nonsexual in nature?

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While there was a chance that, like us, the respondents would deduce the underlying meaning, it was also possible they would be referencing experiences of various other types of harm while completing the survey, which would make the findings less accurate.

But the idea that most people would generally understand what is meant by “community violence” without them ever having to explain it clearly, is evidence of our collective socialization. The nonprofit industry has adopted the ancient political tactic of normalizing dog whistle terms that thrive upon insinuation and unconscious biases.

There is a reason we are so hesitant to say exactly what we mean by “community violence.” Is it because being more explicit would seem racist, and we do not want to grapple with the awkward question of why it seems racist?

It might lead us down a rabbit hole of further analysis:

- Does it feel racist because we are explicitly saying that violence comes from Black people or poor Black communities?

- Is the above assertion true, or do we have a tendency to focus mainly on the violence that comes from Black people?

- Is the violence coming from Black people more prevalent, or is the data more readily available?

- If poor Black communities have the highest rates of violence, have we been proposing adequate solutions, and are they working?

- Is the nonprofit industry designed to provide Band-Aid solutions rather than to address the root causes of violence in poor Black neighborhoods?

- Do we prefer to continue our use of dog whistles instead of interrogating the core beliefs behind them?

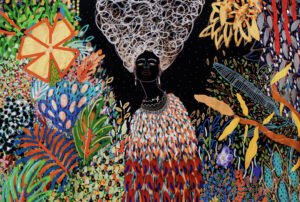

The core belief behind the use of the term “community violence” is that violence is inflicted by and upon Black youth. While this does exist, it is ironic that our impression of community violence does not typically include police brutality, racial profiling, or mass incarceration of Black youth. It does not include the fact that they live within white supremacist domination that is violent both metaphorically and literally, with predatory institutions and systems designed to inflict harm in insidious ways. Our definition of community violence inherently requires us to “fix” or “police” the poorest, most accessible agents of harm while obscuring the role of more powerful agents of harm. The nonprofit and other industries are then invited to focus on finding low budget, minimal effort ways to patronizingly help the scapegoat, while the systems and people that create the conditions within the community go unchallenged.

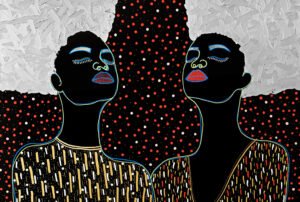

During slavery, Black men were forced to fight each other for the entertainment of the white overseers. The modern equivalent is the fact that although white supremacy is the biggest threat to the Black male’s power and autonomy, he is conditioned to view other Black men as accessible targets for his indignation, due both to his proximity to them and the notion that there are less consequences for intraracial conflict.

Different forms of systemic racism interlock to trap the most vulnerable Black men, those in the “hood,” in a web of hopelessness. It starts at home, with parents who may be so focused on surviving life themselves that there is little time for protecting their kids. It continues at school, where mostly white teachers are hostile and the curriculum erases their identity, where they quickly learn they are not the default idea of a child and the school-to-prison pipeline is the only aspect of education designed with them in mind. It steadily progresses when they are forced to navigate both a conflict-laden street culture and the lurking presence of cops who view them as targets for harassment or an easy way to make good arrest numbers. They quickly realize that money is the key to a better life, but then face severe discrimination during the hiring process for even menial jobs and regular mistreatment in the day-to-day work.

Our current approach is to superficially acknowledge this societal backdrop while crafting solutions that treat the problem as a moral failing on the individual’s part. Shirley Carswell puts it this way: “When white men respond to their life circumstances with gun violence, it’s treated as a public health problem, brought on by mental illness and stress. When Black men do, it’s portrayed almost solely as a criminal issue, caused by lawlessness and moral failing.”

These days, nonprofits are skilled at paying lip service to the values of racial justice, then implementing programs that never address the root of the problem. Therefore, we can decide that the term “Black-on-Black crime” is racist all we want; it doesn’t matter because we inherently believe that the concept is true, and we continue to blindly operate from that belief in every way possible.

This is why countless studies are based on analyzing the effects of the harm Black people do to each other but never why it happens, or the role of social institutions in perpetuating that harm. This is why the police and other entities within the justice system can partner with nonprofits to pay them into complicity while maintaining the illusion of reform. Lastly, this is why our very definition of community violence refers not to an environment of violence cultivated by the state or the police but instead to the violence perpetrated by marginalized Black people.