Detroit Institute of Arts Grand Bargain announcement, A Healthier Michigan

April 29, 2015; NPQ Original Reporting

The Kresge Foundation’s Rip Rapson and former Detroit emergency financial manager Kevyn Orr held their audience spellbound at the Council of Foundations annual meeting as they described how Detroit’s foundation community, including a couple from outside of the city but with Detroit roots or connections like the Ford Foundation and the Knight Foundation, came together for the “Grand Bargain” that helped the Motor City out of bankruptcy. While the story of the Grand Bargain has been extensively reported in a number of newspapers and journals, including Nonprofit Quarterly, most foundation leaders hadn’t had an opportunity until this panel to hear directly from Orr.

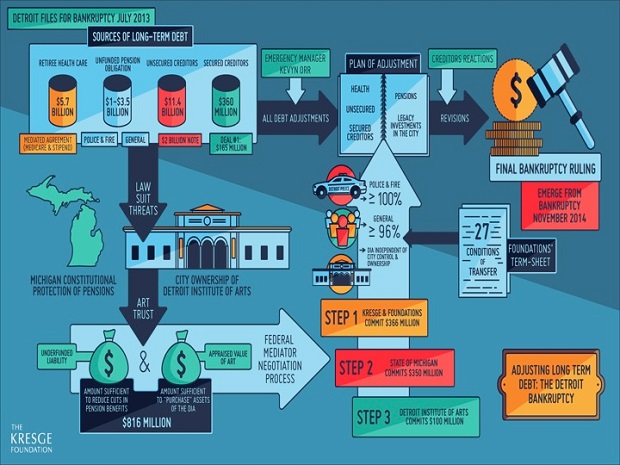

Both Orr and Rapson explained, to put it briefly, that the deal around the Detroit Institute of Art collection and the City’s public pensions was pretty much the linchpin to the bankruptcy deal. Without the foundations’ protection of the DIA collection, there would have been a decade of litigation over any possible sale of the city-owned artwork; not protecting the modest pension levels of Detroit’s retired police, fire, and other city employees would have been a violation of the Michigan constitution’s protection of public pensions, leading to yet more litigation.

Rapson used a very easily understood graphic of the elements of the Grand Bargain—the foundations’ $366 million, the state of Michigan’s contribution of $350 million, and the DIA’s own reluctant commitment of $100 million toward a roughly $850 million pool that succeeded in holding the pensions, hardly “gilded,” relatively harmless.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Some of the story’s details were probably new to listeners. Orr and Rapson discussed their political discussions with the state, including not just Governor Snyder, but state legislators from other parts of the state who had little love lost for Detroit and were hardly predisposed to put up tax revenues from their constituents to rescue a city whose problems they might view as self-inflicted. Orr’s description of his thinking as financial manager to put Detroit’s Belle Island into the deal as a piece of putting at least some Detroit assets on the line was interesting, especially with Belle Island’s history as a “sundown” community. Orr mentioned—and Rapson confirmed—stories of how creditors unhappy with having to take a haircut on what they thought they should be repaid called foundation board members to complain and pressure them about the deal.

The new details about the Grand Bargain retold a story from what is now Detroit’s past. The challenge in the discussion at the Council on Foundations annual meeting, all too brief because of the conference format of breakout sessions limited to one hour, was to pivot to the present and future of Detroit. While the city has emerged from bankruptcy, it hasn’t come back to prosperity for the vast portion of Detroiters who are poor, unemployed, and living in neighborhoods without the kinds of basic services that most municipalities deliver to their citizens as a matter of course. As a backdrop to the Rapson/Orr discussion, participants were well aware that in another majority black city, Baltimore, people were in the streets in a paroxysm of public frustration expressed in violence, burning, and looting.

Orr was very clear that he was aware of that potential in Detroit. Noting that there were “active units” in Detroit trying to spur unrest like that seen in Ferguson and now Baltimore, Orr said he was strongly motivated to keep Detroit off the front page of the New York Times for that kind of unrest, with which he was personally familiar from the killing of Arthur McDuffie in 1979, when unrest in Liberty City and Overtown led people to question whether Miami’s revival might have been stalled or reversed.

In these brief moments at the end of the hour-long panel when Rapson and Orr engaged the audience about Detroit’s upcoming challenges, it was clear that answers for the present and future of Detroit have yet to emerge. Orr acknowledged that much of the attention to the so-called “rebirth of Detroit” has focused on the downtown, where the acquisition of office space has led to a new dynamic in roughly nine square miles of the city. But the whole of Detroit is probably fifteen times that size, meaning that most of Detroit is far from the rebirth that Orr described as including yuppies jogging safely at night along Woodward Avenue with their Labrador retrievers in tow.

Both Rapson and Orr were straightforward in acknowledging how much there was to be done. Orr in particular emphasized education, without needing to mention, as NPQ has, that the school system is also next to bankrupt and facing a major state intervention and restructuring. Rapson referenced the Detroit Future City plan that Kresge spearheaded, containing strategies for the city’s long-suffering neighborhoods. To Orr, one of the big questions for the city is, as in Ferguson and elsewhere, what is the community going to be able to do for the young black men of Detroit who, as in other places, are lagging behind in jobs, income, and education.

Detroit’s neighborhoods have had their hopes raised and dashed by innumerable plans that were going to be the answer to reverse their long downward slides. Now neighborhood residents get to watch as the downtown is repopulated by Quicken mortgage loan packagers and high tech entrepreneurs, with downtown office vacancy rates shrinking rapidly and newcomers reaping the benefits of Detroit’s low property values. Detroiters who own properties with low residential values, in neighborhoods lacking many basic municipal services like working streetlights and regular garbage pick-up, may not be rapid or direct beneficiaries of the city’s new job creation. The revival of Detroit’s neighborhoods so that long-term Detroiters benefit from the city’s progress must be the next challenge for Detroit’s foundation community, else the Grand Bargain works for the DIA and the pensioners but not for the citizens of Detroit who stuck it out when hundreds of thousands of their neighbors decamped for alternate cities and regions.—Rick Cohen