June 22, 2016; New York Review of Books and Chicago Tribune

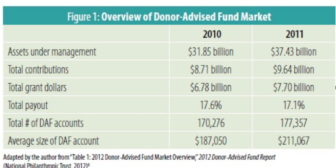

Esteemed BU Professor Ray Madoff and lifelong philanthropist Lewis Cullman have long advocated against low payouts from charitable vehicles of all kinds. By the end of 2016, the largest pooled charity in the United States will be the Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund, with more than $2 billion in assets in 80,000 donor-advised funds managed on behalf of 132,000 fund investors. Their growth has been nothing short of phenomenal and they have been in the sights of Madoff and Cullman for some time. Their recent joint piece in the New York Review of Books takes on that industry in no uncertain terms:

Donor-advised funds have been a bad deal for American society. They have produced too many private benefits for the financial services industry, at too great a cost to the taxpaying public, and they have provided too few benefits for society at large. When we consider their overall effect, we see that rather than supporting working charities and the beneficiaries they serve, they have undermined them. Congress should enact a rule requiring that donor-advised funds be distributed to operating charities within a reasonable period of time in order to assure a regular flow of money to working charities. In addition, private foundations should not be allowed to satisfy their payout rules by making contributions to donor-advised funds.

That last point is well taken; NPQ has previously written about these kinds of transfers, the surfacing of which is made more difficult by the lack of transparency in DAFs.

As most NPQ readers know, the large investment firms, including Fidelity, Vanguard, and Schwab, offer DAFs to their customers as a method of carrying out philanthropic activities, but also as lines of their business. The IRS considers these accounts charities. Once resources are transferred into these accounts, the donor relinquishes ownership and cannot withdraw them. In return, they get an immediate tax break while buying time to actually disburse the money. After the death of the donor or donors, funds remaining in the DAF account may be advised by the donor’s heirs.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Additionally, by transferring certain types of appreciated assets into the accounts, donors can achieve a larger deduction on their taxes than they would if the investments were sold and the proceeds donated. Fidelity and other investment firms, like community foundations, charge maintenance fees and invest the account resources in the stock market and other investment opportunities. Unlike foundations, which must distribute up to five percent of assets in grants, gifts, and administrative expenses each year in order to avoid excise taxes, donor-advised funds are not required to make any such annual distributions. But they do, at least in aggregate. Though studies of DAF payout activity are somewhat inconsistent, Schwab Charitable and Fidelity Charitable report ninety percent and ninety-two percent of assets in the accounts are distributed to charities within ten years of receipt. In 2012, the IRS placed the annual median payout rate of all of the funds at ten percent of account total value, but this estimate is low against others that hold payouts at around twice that. Even 10 percent is twice the rate of required payout at foundations, other than the odd spend-down entity.

We cannot see into the individual funds behind the curtain, which makes concerns over transparency and accountability legitimate concern. Some use their funds as mere passthroughs while others make virtually no grants, letting the assets grow for later in the manner and image of a foundation with intentions of perpetuity but without the usual requirements for payout.

These dual problems of lack of transparency and lack of required payout from individual funds get under the skin of astute observers. In 2012, Rick Cohen comprehensively took on donor-advised funds and found them less than compelling. The article is worth a read in the face of Madoff and Cullman’s criticisms, but in it, he notes an observation of Kim Laughton, CEO of Schwab Charitable.

Schwab Charitable’s DAF payouts routinely top 20 percent. At NPT, Heisman takes pride in the fact that, in the organization’s 16-year history, it has raised $2.5 billion but given away more than $1.4 billion. These are payout ratios that are only approached in the foundation world by spend-down foundations. With payouts that high, the investments of the DAFs in mutual funds, including socially responsible funds (Schwab now offers one managed by Parnassus), move relatively quickly compared to foundation dollars that sit in banks and equities for much longer periods of time. In doing so, DAFs are part of a movement in philanthropy that stands as an alternative to ginormous foundations created by millionaire and billionaire families whose grantmaking is determined by a handful of rich board members. In contrast, DAFs are, dare we say it, an instrument toward democratizing philanthropy, putting more philanthropic decisions into the hands of ordinary Americans who may not be charter members of the one percent club. Hopefully, as technology improves and databases on charities become more widespread and functional beyond just financial measures, and as the nation becomes more aware of easy mechanisms for charitable giving, entities such as Schwab, NPT, and community foundations will attract more donors and stimulate increases in thoughtful, strategic charitable giving.

More transparency and tracking are doubtlessly needed as these entities grow, but if and how growth of DAFs has affected charitable giving for the worse is unclear. According to Madoff, the amount of giving has remained at about two percent of disposable income for the last forty years. At the same time, donor-advised funds have grown from two percent of total giving among the 400 biggest charities in the U.S. in 1991 to eighteen percent in 2015.—Gayle Nelson and Ruth McCambridge