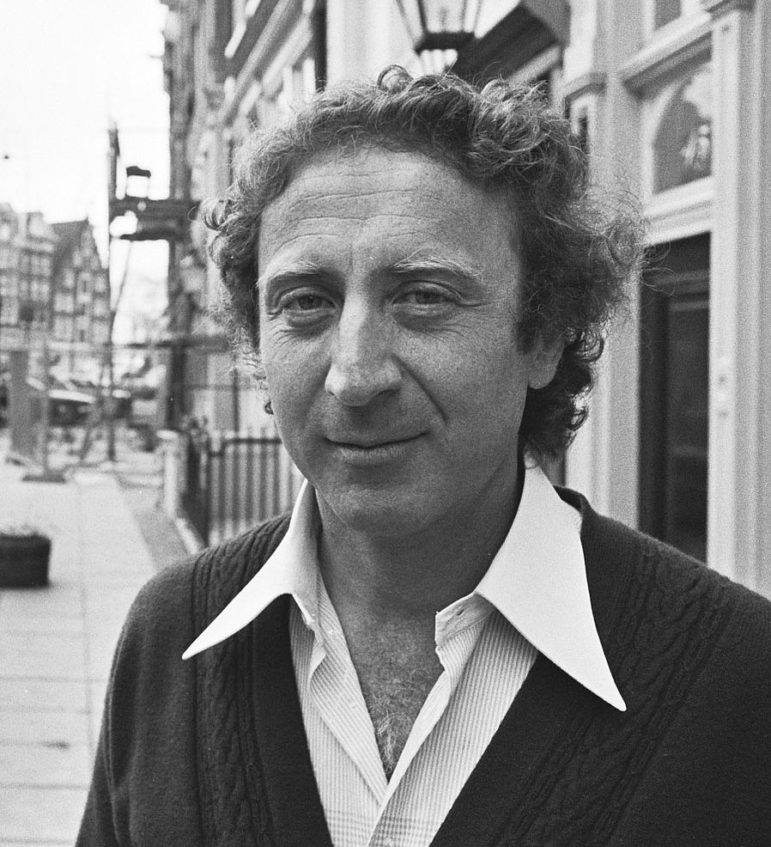

Following the news of Gene Wilder’s death on Sunday, Jared Keller wrote a moving and much-shared tribute to Wilder’s devotion to his third wife, Gilda Radner, and to his efforts to help others afflicted by the ovarian cancer that took Gilda’s life.

Wilder co-founded Gilda’s Club in New York City in 1991, perhaps not coincidentally the last year he made a movie. Soon, Gilda’s Club chapters and similar organizations proliferated around the world. This initiative offers emotional and social support to help fortify the medical care given to people with cancer. The club also serves as a support group for patients’ families and friends. The nonprofit clubs offer networking groups, lectures, workshops and social events in a nonresidential, homelike setting. For years to come, especially for those who never saw one of Wilder’s iconic movies, Wilder’s philanthropy and advocacy inspired by his love for Gilda may be his most notable legacy.

Gilda Radner was the Lucille Ball of her generation. She is best known as one of the original cast members of Saturday Night Live. She met Wilder on the set of the film Hanky Panky. In her book, It’s Always Something, Gilda wrote about her experience living with cancer. She spoke of establishing a support community in New York, and following her death, Wilder and many of Gilda’s friends did just that. Wilder also founded the Gilda Radner Hereditary Cancer Program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

Wilder became an activist as well, testifying before Congress, which resulted in $30 million being allocated to federal ovarian cancer research. Keller reports that Wilder ushered in “a new era of openness in conversations around cancer.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The medical community has since realized the benefits of support groups in treating cancer: Two studies from the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) in 2007 and 2013 both emphasize the role in psychosocial support not just for cancer patients, but their families, friends, lovers, and health care providers.

Here is a closing excerpt of the wrenching essay Wilder wrote for People magazine describing in painful detail how Gilda’s symptoms had gone undiagnosed until it was too late.

I’ve learned a lot about ovarian cancer since Gilda died, but I’ve avoided talking about it in such a public way because I don’t want to pretend to be a doctor. But we have to learn from the past, from the mistakes. I’m hoping in some small way to help the other Gildas out there. When I was walking through the halls of Congress, waiting to testify, I could hear that raspy, whining voice—Gilda’s—saying, “Go on, don’t make such a big deal of it. Now, don’t get mushy, don’t get melancholy. You’re not the victim. I was the victim. Don’t go soft and sad and poetic, as if a great tragedy happened to you.”

Okay, okay, Gilda. Now will you stop hollering in my ear!

In our world of philanthropy, people with means sometimes seek to burnish their legacy with gifts that etch their names in granite. Wilder etched his name in our hearts and minds by his wonderful talent and his generous and principled actions. For those who saw his uplifting movies, he is the beloved actor from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory and who sang that magical song, “Pure Imagination.” For those fighting cancer and for their family and friends, Wilder is the beloved benefactor and advocate whose Gilda Club helps them believe that love will see them through whatever may come.—James Schaffer